The Revolt of the Eighteen

Plus: a new course about cross-border tensions, a tour of the PATH, and more...

A tense hush fell over the House of Commons. It was a winter afternoon in 1911 and parliament was in session in Ottawa. Debate was underway on a controversial plan to revolutionize Canada's relationship with the United States. The Liberal government had negotiated a new trade deal, promising to reduce and remove tariffs as part of a big step toward free trade with the Americans. Reciprocity. It was a momentous change, a move away from Canada's long-standing preference for trade with Britain in favour of the country's traditional enemies south of the border.

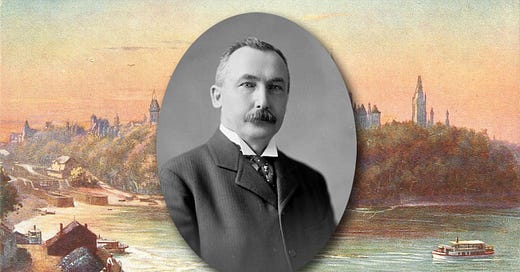

Now, as the House fell silent in anticipation, Clifford Sifton rose to his feet.

Sifton had spent his career as one of the leading members of the Liberal party, a long-time cabinet minister best-known as a champion of Canadian colonialism on the Prairies. He'd been born in Ontario and studied at the University of Toronto, but it was in Manitoba that he began his political career, as a minister in the provincial government. He made his move to federal politics just as the Liberals swept to power at the end of the 1800s and had served under Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier ever since. Sifton became Minister of the Interior, overseeing the departments sending settlers west as Indigenous people were driven off their land and the prairies were being turned into farms. He'd now been working with Laurier for fifteen years. And even after their relationship began to fracture and Sifton resigned as minister, he had continued to support the government as a backbench MP.

But the new trade deal threatened to drive the two even further apart. The proposal was drawing criticism from across party lines. There were Canadians of all political stripes who worried that freer trade with the Americans would leave the country vulnerable to being swallowed up and annexed by the United States.

Many Canadians didn't trust their American neighbours. The War of 1812 had been fought just a century earlier, when the United States invaded the Canadian colonies with an aim to conquer them. It was a brutal, bloody war. And those tensions had never entirely eased. Throughout the 1800s, people north of the border were all too aware that many American leaders still believed in the idea of Manifest Destiny — that the United States had a divine right to rule over the entire continent. It was one of the reasons people from across the British Canadian colonies were driven to unite and form their own country.

Those fears hadn't disappeared in the decades since. The United States had already tried using aggressive tariffs to push for annexation. There had been anger over the way the border had been drawn between Alaska and the Yukon. And Canadians had watched as the U.S. annexed Hawaii and fought a war with Spain that ended with the Americans taking control of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines.

Now, half a century after Confederation, Canada was still part of the British Empire. And that close relationship with Britain wasn't just economically important, but also symbolically powerful. Even as the United States grew to become our biggest trading partner, our tariffs favoured the British. They varied from one product to another, but averaged somewhere around 28%. Many Canadians saw them as a bulwark against American influence, protection against a gradual slide toward annexation, a guarantee of independence.

Clifford Sifton seems to have been one of those Canadians. He came out against reciprocity before it had even been announced. During a talk to the Canadian Club in Montreal, he argued that trade with the U.S. was dangerous. "If we enter upon trade relations of an extensive character with the United States … what is the inevitable conclusion? Must not our trade and business and very life become mixed with theirs, so that we shall become increasingly dependent upon them, with the ultimate end of a political union? … My view is that the best way of continuing good relations between Canada and the United States is that each should do its own business independently and have no entanglements — nothing in the world to quarrel about."

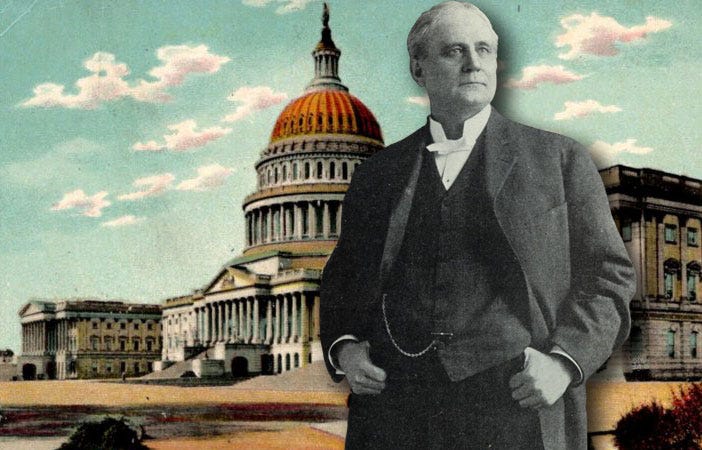

In the weeks since the deal was announced, some American politicians had been stoking those fears. As the United States Congress debated reciprocity, a leading Democrat named Champ Clark gave a speech promoting the agreement as a step toward annexation. "I look forward to the time," he declared, "when the American flag will fly over every square foot of British North America up to the North Pole… I have no doubt whatever that the day is not far distant when Great Britain will joyfully see all her North American possessions become part of this Republic." His speech was met by enthusiastic applause in Congress and by horror in Canada.

The Chicago Tribune knew it was a mistake. "He lets his imagination run wild like a Missouri mule on a rampage," the paper reported. "Remarks about the absorption of one country by another grate harshly on the ears of the smaller." But Clark wasn't alone. His views were echoed in American newspapers and by other American politicians. One Republican even introduced a motion asking President Taft to open talks with the British about annexing Canada. His resolution didn’t go anywhere and some historians think it was nothing more than a clever political ploy devised to whip up opposition to the trade deal in Canada. But whatever the motivation, damage was done.

The relationship between the two countries was suffering. The press reported that anti-American feeling in Canada was at an all-time high. Some American newspapers warned their readers not to identify themselves as visitors from the U.S. if they travelled north of the border because they'd be putting themselves in danger. There were false rumours of American immigrants abandoning Canada by the thousands and even of attacks being planned on American consulates.

It all helped turn Canadians against Laurier's deal. "Somewhere along the line," historian A.B. Hodgetts wrote, "a prosperous, confident Canada had concluded that the tariff was the price to be paid for national independence."

And so, as Clifford Sifton rose to his feet in the House of Commons, his fellow MPs waited breathlessly to hear what he had to say. How far would he go in his opposition to the deal?

He didn't leave them in suspense for long. “I have found it," he admitted as he began, "the most important question which has come before this House since I have had the honour of being a member of it." Then, he quickly dropped his bomb. "I cannot follow the leader of the party with which I have been identified practically all my lifetime… I take the only course which I can take and retain my self-respect.”

The Conservatives burst into applause. Clifford Sifton, the famous Liberal, was breaking with his party.

And that was just the beginning of his speech. Sifton would keep talking for the next two hours, tearing the trade deal to shreds. He claimed it had been introduced without enough consultation, would upend the economic ties between the provinces, and was bound to lead to American domination. “We propose to … put ourselves in dependence upon the markets of the United States. How long will they remain open? Nobody knows. It may be one year or five years… They say that the United States is friendly. Well, perhaps it is. What will it be in a year from now? Does anybody know? … We are putting our head into a noose.”

Sifton's speech sent a shockwave through Canadian politics. And he didn't stop there. The former minister had already secretly begun to organize against his own party. He threw his support behind the Conservatives and began looking for other Liberals willing to break with Laurier over the tariffs.

He found them in Toronto.

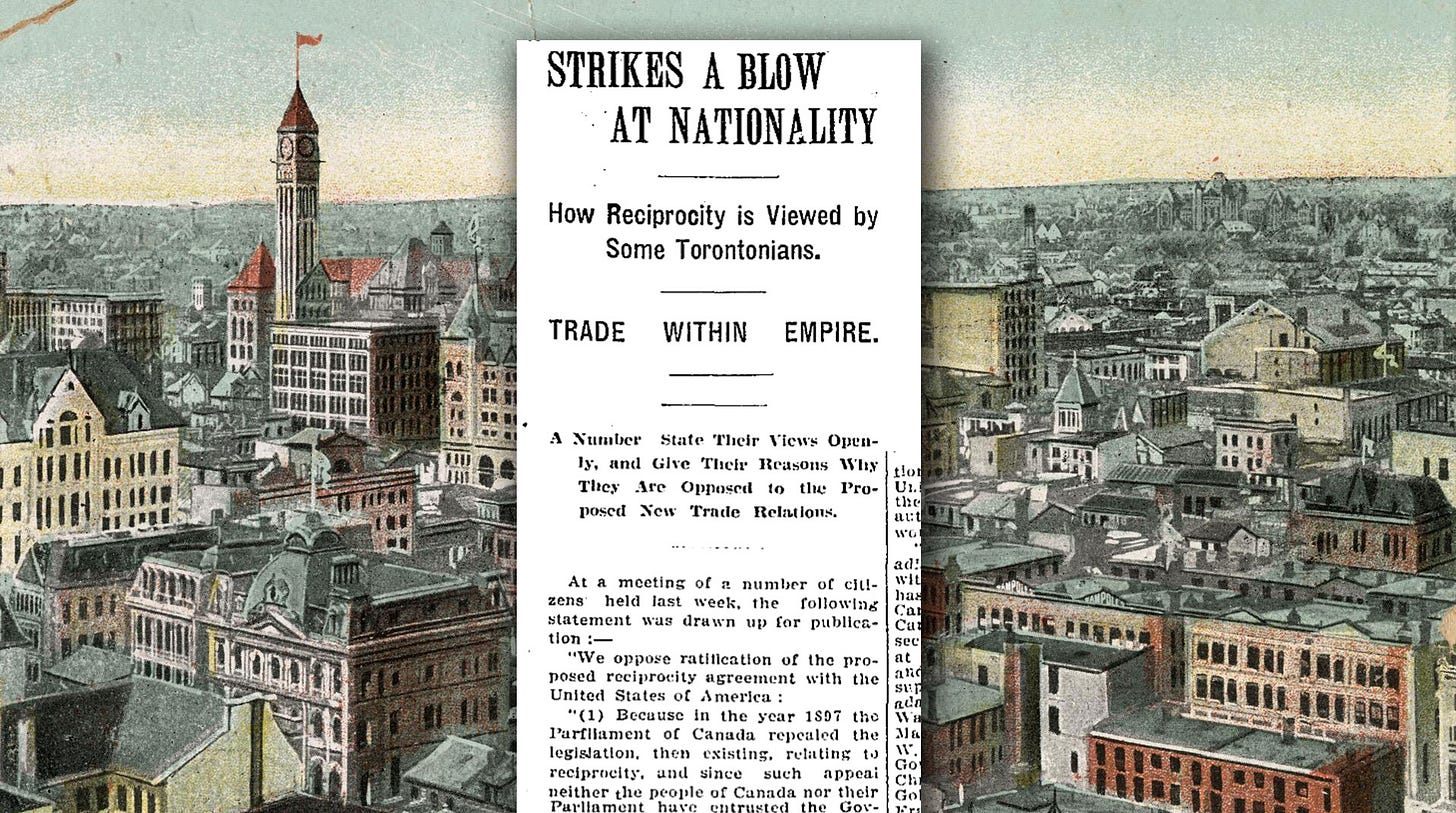

It became known as the Revolt of the Eighteen — and some believe Sifton helped orchestrate it. Toronto's business leaders weren't happy with the deal. The local Board of Trade had voted overwhelmingly against it; during the meeting, Sir Byron Edmund Walker, president of CIBC, had declared, "Although I am a Liberal, I am a Canadian first of all." Just days later, he was one of eighteen prominent Torontonians who released a manifesto opposing reciprocity. The signatories were all powerful business leaders who had previously supported the Liberals. The list of names included some of the wealthiest and most influential men in the city: the president of Eaton's, directors of big insurance companies like Manufacturer's Life (Manulife) along with grocery chains and railroads and energy companies and piano-makers, even a former Lieutenant-Governor and the managing director of the Christie's cookie company.

"Canadian nationality," they wrote, "is now threatened with a more serious blow than any it has heretofore met with, and … all Canadians who place the interests of Canada before those of any party … should at this crisis state their views openly and fearlessly."

The Toronto Eighteen published a whole list of reasons to oppose reciprocity. They included everything from the prosperity Canada had enjoyed under the current system — it was now the fastest growing economy in the world — to a desire to maintain ties with the British Empire. The deal, they said, would leave the country vulnerable to American whims. "After some years of reciprocity under the proposed agreement, the channels of Canada's trade would have become so changed that a termination of the agreement and a return by the United States to a protective tariff against Canada would cause a disturbance of trade to an unparalleled extent." Dropping the tariffs, they argued, would "make it all the more difficult to avoid political union with the United States."

There was plenty of reason to view the motives of the Toronto Eighteen with suspicion. They may have been more worried about protecting their own profits than about patriotic pride. They'd all gotten rich off the current system and reciprocity was expected to hurt big industrialists in the east while helping independent farmers in the west. Plus, members of the group included close allies of Sir William Mackenzie, the tycoon who had once owned our city's private streetcar company and was now head of the Canadian Northern Railway. He was accused of using the Toronto Eighteen to settle a personal grudge, furious that when Laurier's government gave his company subsidies, they'd also helped his competitors at the Grand Trunk. If the Conservatives came to power, Mackenzie stood to gain millions in contracts and subsidies from the new government. One prominent Liberal called it "an orgy of corruption." He claimed Mackenzie gave the Toronto Eighteen a blank cheque which they filled out for the sum of two million dollars — more than fifty million in today's money.

They would use that fortune to help bring down the government.

The Revolt was the beginning of the end for Wilfrid Laurier. Sifton and the Toronto Eighteen struck a deal with Robert Borden, leader of the Conservatives. He, too, was against reciprocity. "From a national standpoint," he wrote, "it is suicide." And so, they would work together to kill the trade deal. Sifton and the Toronto Eighteen would throw their support behind the Tories and in return they were promised influence over the future Conservative government. It was, according to historians David MacKenzie and Patrice Dutil, "One of the most remarkable political bargains in Canadian political history."

In the weeks to come, Sifton and the Toronto Eighteen would fan the flames of outrage. They helped establish anti-reciprocity organizations that kept the issue on the front page. A big rally was held at Massey Hall, with the venue draped in Union Jacks and the stage adorned with a huge map of the Canadian railways that united the provinces. A crowd of four thousand people waved flags and cheered on speeches by the Mayor of Toronto, the head of Board of Trade, and members of the Eighteen. "The gathering was on the whole," according to The Montreal Gazette, "a most convincing expression of Toronto's opinion on reciprocity proposals."

Not everyone was against the deal. A few loyal Liberals heckled the speakers that night. And when Sifton and members of the Toronto Eighteen spoke at another event in Montreal, a riot broke out. Liberal-supporting McGill students attacked Sifton's carriage and set it alight. They smashed shop windows and broke into cars, then kept police at bay with a barrage of snowballs. But the tide was turning. The Liberals were losing public support.

The Tories seized their opportunity. With Canadians souring on the trade deal and the unexpected support of the Toronto Eighteen giving them new confidence, the Conservatives waged a filibuster campaign against the bill. Parliament was paralyzed. And in response, Prime Minister Laurier made a dramatic decision.

He called for an early election.

It proved to be a disastrous move. The 1911 election campaign would be an ugly one. The Conservatives played up anti-Catholic prejudice against Laurier and anti-Asian bigotry in the West. In British Columbia, they ran on a slogan promising "A White Canada." Meanwhile, in Quebec, Laurier's support had already been eroded by his pledge to create a Canadian navy. And all through the campaign, Borden hammered away at the trade deal. In English-speaking Canada, reciprocity with the United States became the central issue of the election.

Sifton wasn't running for re-election himself, but he hit the campaign trail anyway. This time, it was on behalf of the Tories, aiming to defeat the same government he'd served for so long. He created a mailing list and sent copies of his speech in the House of Commons to voters, along with an anti-reciprocity pamphlet. He denounced the trade deal at election events while also serving as a key link between the Conservatives and the Toronto Eighteen. Some members of that group gave their own speeches; a few even appeared on stage with Borden during a Conservative election rally at Massey Hall.

Two weeks before election day, the Tories got one last major boost. Rudyard Kipling weighed in on reciprocity with an editorial on the front page of The Montreal Star. “I do not understand," he argued, "how nine million people can enter into such arrangements as are proposed with ninety million strangers on an open frontier of four thousand miles, and at the same time preserve their national integrity… It is her own soul that Canada risks to-day.”

When it finally came time for voters to head to the polls, the passions aroused by the fear of annexation were on full display. Canadian elections weren't as violent as they had once been, but the country was tense with anticipation. In Montreal, the police chief was preparing for riots. In Winnipeg, two hundred police officers kept guard at the polling stations. In New Brunswick, a fight broke out between Liberal and Conservative supporters. When a man in that province was killed by an umbrella to the eye, some blamed it on the political violence.

The intense feelings of that election day were summed up by a famous Toronto poet named Wilson MacDonald who voted against reciprocity. He's quoted in Canada 1911, MacKenzie and Dutil's book about the campaign. "Election day at last," MacDonald wrote. "O fateful day! This night will tell us at last 'Which Flag' [will prevail.] In all my life I never knew the affairs of state to grant me such an hour of sheer ecstasy."

Crowds began to form as soon as the polls were closed in Toronto. Vast throngs gathered outside newspaper offices, waiting anxiously for the results to be announced. As the evening wore on, they grew to sizes never before seen in the city. The entire downtown core was filled with people. The Toronto Daily Star put the number at 100,000. The Globe had it at 150,000. "Never did enthusiasm get to such a height, and never did the heart of the city contain so many people." Both newspapers supported the Liberals, but even they agreed it was "the biggest political night in the history of Toronto."

When the news finally came, it was exactly the result so many in those crowds had been hoping to hear. The Conservatives had won a majority. In Toronto, it was a clean sweep; the Tories took every one of the city's five ridings — and did it easily. Canadians had rejected reciprocity. Laurier's days as prime minister were over. Robert Borden had won. The Conservatives would be in power for the next decade.

Clifford Sifton's career was soon over, too. With his betrayal complete and the election won, he retired from politics. He would eventually end up moving back to Toronto; he spent the last decade of his life living here. His influence quickly waned: Conservatives hadn't forgotten the years he spent as a leading Liberal, while the Liberals now saw him as a traitor to the party. He passed away in 1929 and is buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

In the decades to come, Canadians would continue to debate free trade with the United States. And by the time it became a reality with NAFTA, the old political lines had shifted once again. By then, it was the Conservatives under Brian Mulroney who had become the champions of the idea. Liberal leader John Turner railed against it with many of the same arguments the Tories had used nearly a century earlier.

But on that rainy election night in 1911, that was all still far in the distant future. As the results were announced to the crowds, the celebrations began. Anti-reciprocity supporters paraded through the streets of Toronto waving flags and throwing their hats into the air. Some blew whistles and horns, climbed telephone poles or gathered on rooftops. The sounds of thunderous cheers reverberated off the city's early skyscrapers. Marching bands played patriotic songs as lanterns and torches lit their way. Conservative candidates gave victory speeches across the city. One of them stood before the enormous crowd at King & Bay. He thanked the voters and the old Liberals who had switch their allegiances. "To-day," he announced, "the Canadian people have won their greatest victory, and foremost in that victory Toronto stands."

Wilton MacDonald was there that night, too, swept up in the throngs on Yonge Street. It was a moment the poet wouldn't soon forget. "It was a sight little short of sublime," he wrote. "I shall sleep little tonight for love of my country… Hereafter it shall be the proudest of privileges to boast a citizenship in a land that refused to sell her birthright."

If you’d like more stories about the history of cross-border tensions between Toronto and the United States, I’m creating a whole new online course full of them. It starts in just a couple fo weeks. You’ll find more information about that below!

It also looks like I’ll be on TVO’s The Agenda next Monday night as part of a panel talking about the Annexation Manifesto of 1849, which I wrote about in the newsletter a few weeks ago here.

You’ll find more information about the book “Canada 1911: The Decisive Election That Shaped The Country” by David MacKenzie and Patrice Dutil here.

If you’d like to learn more about the McKinley Tariff and how some Americans hoped it would push Canada into being annexed back in 1890, Craig Baird shared a thread about it on his Canadian History Ehx Bluesky account here. And he’s got his own post and podcast episode about the election of 1911 here.

Thank you so much to everyone who has made the switch to a paid subscription! It’s your support that allowed me to spend the time doing a deep dive into this story. It took forever! It’s only because of the heroic 4% of readers who support the newsletter with a paid subscription that The Toronto Time Traveller is able to survive. If you’d like to make the switch yourself, you can do that right here:

Toronto vs The United States: A History of Cross-Border Tensions (My New Online Course!)

With threatening news making headlines just about every day right now, I’m feeling more than a little unsettled. So I thought I’d follow up my History of Hope & Resistance in Toronto with another online course created in response to today’s events, devoted to the long, long history of tensions between Canada and the United States…

Course Description: Toronto hasn’t always gotten along with our neighbours to the south. Originally founded as a home for refugees from the American War of Independence, our city was created in direct contrast to the United States. And in the centuries since, cross-border tensions have deeply shaped our history.

Generations of Torontonians have stood strong against invasion and threats of annexation while working hard to make our city a safe haven for those fleeing hardships south of the border. In this online course, we'll explore those stories in four weekly lectures — from the War of 1812 to the Underground Railroad to the draft dodgers who refused to fight in Vietnam. Faced with our own unsettling times, we'll take a look back at the Torontonians who have lived through frightening eras before us — and how, in the process, they made our city into the place it is today.

When: The course begins at 8pm on March 24 and runs every Monday night for four weeks.

Where: Over Zoom. All lectures will also be recorded, so if you have to miss any of them you can watch them whenever you like. The recordings will remain available for the foreseeable future.

Cost: Pay what you like!

Secrets of the PATH — A New Walking Tour

There are strange tales hidden beneath our city, found in the most unlikely places. The PATH is filled with them: from pirates and curses to dead whales and mysterious disappearances. So, we’ll spend an afternoon searching for those bizarre histories in the nooks and crannies of our subterranean mall. And we’ll be joined by a special guest: Toronto Star reporter Katie Daubs, who once spent two weeks living in the PATH!

When: Sunday, March 23 at 3pm.

Where: Meet inside the Eaton Centre — outside Treehouse Toys (near Queen Subway Station). The tour will last about 2 hours and end not far from the intersection of Bay & Queen’s Quay.

Price: Pay what you like!

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything new in Toronto’s past…

MORE NEW BIOGRAPHIES NEWS — Natasha Henry-Dixon has released three more new entries in the series of biographies she’s writing about people enslaved in Upper Canada for The Dictionary of Canadian Biography…

The first is the story of Henry Lewis, who was enslaved by William Jarvis and escaped to the United States before trying to officially buy his freedom. Read more.

The second is Peggy, who was enslaved in Toronto (the town of York back then) by Peter Russell and his sister Elizabeth — along with her children Amy, Jupiter and Milly. Read more.

And the third is Peter Martin, who gained his freedom by fighting for the British during the American Revolution. He later witnessed Chloe Cooley’s resistance to her enslavement at Niagara. His account of the incident helped inspire the introduction of the Act to Limit Slavery. Read more.

SELF-GUIDED WALK NEWS — Natasha Henry-Dixon has also created a pair of self-guided walking tours exploring the history of Black Torontonians in the 1700s and 1800s. YFile wrote a piece about them with more information and links to both. Read more.

RACIST OMNIBUS NEWS — Eric Sehr has two new posts in his project about the history of Brockton Village…

The first traces the history of the neighbourhood’s shifting boundaries. Read more.

While the second shares the story of a Black mother and child — Mrs. Garnett and her sick son — who were refused a ride on early public transit by a bigoted omnibus driver. Read more.

SWAGGER NEWS — With the future of Old City Hall up in the air, Jamie Bradburn wrote about the building’s architect, E.J. Lennox and how he “gave Toronto its early swagger.” Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

SEARCHING FOR ARCHIVAL PHOTOS — A ZOOM PRESENTATION

March 11 — 7pm — Online — Back Lane Studios

“Are you doing some property, family or other historical research? Are you looking for photos in archives but can’t find anything relevant? Kirsten Gunter, who is working on a Back Lane Studios project, was searching online to no avail for photos of the Midtown Bakery. It was located in the same building as her first Toronto apartment on Bloor across from Honest Ed's. Despite all of the photos of the popular store on the south side of the street, she could find nothing that might have included the bakery. Fortunately, Wayne Reeves is here to help us out. Recently retired as Chief Curator for the City of Toronto, Wayne knows a thing or two about navigating archival collections!”

$5 suggested donation.

BEFORE NEON, PLASTIC & DIGITAL: TORONTO’S EARLY BUSINESS SIGNS

March 12 — 7pm — The Beaches Sandbox – The Beach & East Toronto Historical Society

Wayne Reeves, former Chief Curator for the City of Toronto, gives a talk about the early history of business signs in the city.

Free!

THE BEATLE BANDIT: A TRUE CRIME PRESENTATION

March 20 — 7pm — Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Join Toronto-based journalist and author Nate Hendley as he presents his award-winning true-crime book, The Beatle Bandit, published by Dundurn Press. Nate will discuss the story that inspired the novel as well as the writing and research process that went into creating this book. There will be an accompanying PowerPoint presentation and time after the talk for audience questions. Books will be available for sale and signing at the talk. Pre-registration is required and spots are strictly limited!”

$17.31 for members; $22.63 for non-members.