Toronto vs. The Annexation Manifesto

Plus: Old City Hall as the Museum of Toronto, Henry Moore, the Hearn, and more...

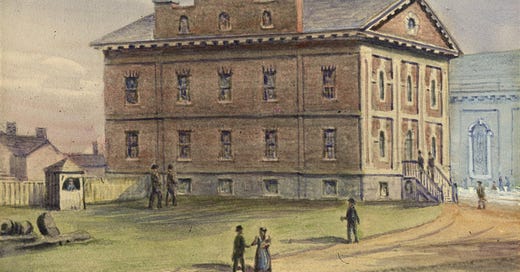

It was a rainy October day in 1849; the kind of wet and dreary weather that keeps people inside where it's cozy and warm. But on that autumn Saturday, there was important work to be done. Some of the most powerful politicians our city has ever known made their way through muddy roads and over slippery wooden sidewalks, heading for the courthouse on King Street. There, inside the Grand Jury Room, a meeting was being held. It was attended by some of the most bitter rivals in Canadian history — political leaders whose parties had spent decades at each other's throats. There were men in that room who had denounced each other as traitors. Who had whipped up angry mobs to burn each other in effigy. Whose supporters had beaten each other bloody in the streets. But on that October day, they came together in response to a threat so urgent and alarming it united them in common cause.

They were there to stand up against the idea that Canada should be annexed by the United States.

The meeting was organized in a hurry, a swift reaction to disturbing news out of Montreal. Some of that city's leading citizens had just published a document that became known as the Annexation Manifesto. It was a declaration signed by more than a thousand people calling for the Province of Canada to become part of the United States. Many of the signatories were familiar names, like John Redpath (the sugar tycoon whose company headquarters now sit on the Toronto waterfront), two Molson brothers (heirs to the brewing fortune and powerful bankers in their own right), Cornelius Krieghoff (the famous artist whose work you'll find at the AGO), and future prime minister John Abbott (who would later dismiss his support for annexation as a youthful mistake).

Momentum for the idea had been building all summer. For years now, the two British colonies of Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario and Quebec) had been united as the Province of Canada. And two major political factions had been battling over its future. One on side: the Reformers and their allies (pushing for democratic reform and Responsible Government, the system we have today). On the other side: the Tories and their allies (who opposed it).

That spring, the Reformers had finally won. After years of tension and violence, the Governor General signed a controversial bill into law despite the Tories' outraged opposition to it. By refusing to veto the Rebellion Losses Bill, Lord Elgin was acknowledging that parliament now had the real power — that the elective representatives of the Canadian people could pass their own laws without them being vetoed. Responsible Government had arrived.

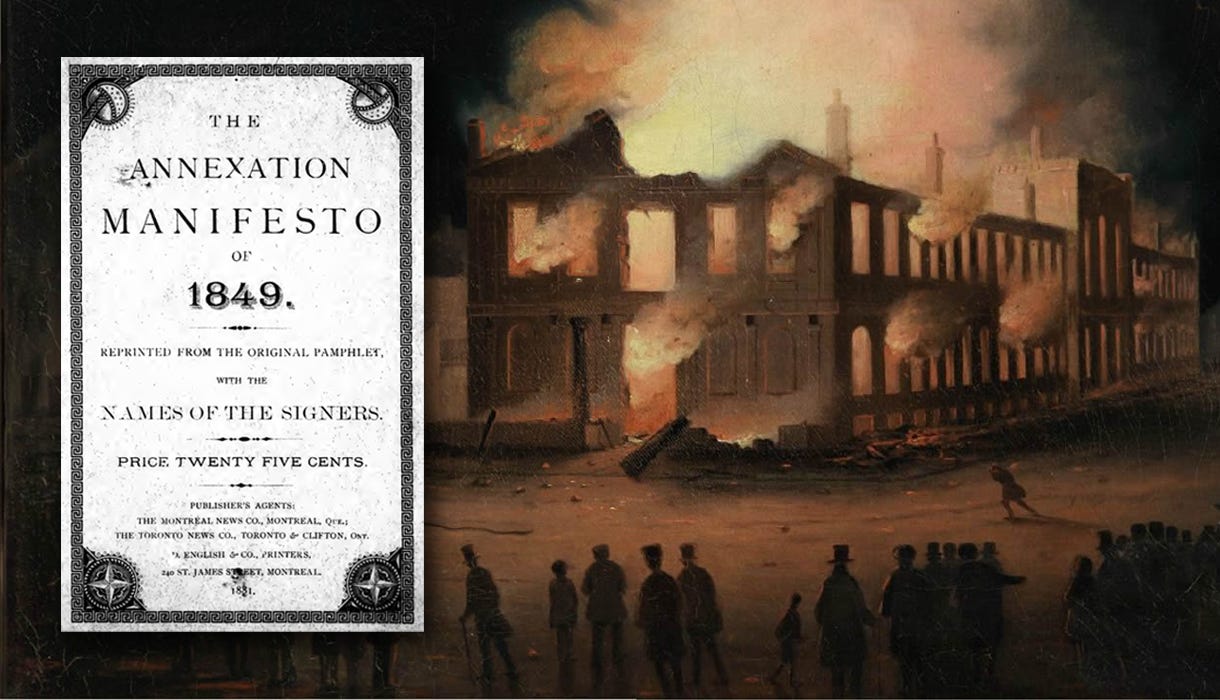

To the Tories and their allies, it was an outrage. There were riots and gunfights in the capital of Montreal. That night, they burned down the parliament buildings in protest.

And that wasn't the only thing they were angry about. By the end of the 1840s, the world was sinking into a global depression. The timing was terrible for Canadians. Just a few years earlier, the British government had embraced free trade by repealing the Corn Laws — protective tariffs on grain. Under those laws, Canadians selling grain to Britain had been subject to lower import duties than competitors outside the Empire. But now that advantage was gone. The Canadian economy suffered.

Many wealthy Tory business owners and politicians were incensed. And the arrival of Responsible Government seemed like yet another outrage — a betrayal of the loyalty they'd shown the British Empire for decades. Many had even put their lives on the line for it, fighting the American invaders during the War of 1812 and then homegrown radicals during the Rebellions of 1837. Now, the British had abandoned them to the kind of democratic reforms they'd spent their whole lives keeping at bay. By the summer of 1849, conservatives across the Province of Canada were reeling.

"The Tory Party is annihilated," the famous Reformer George Brown declared, "but the atoms of its remains are to the fore, and their very prostration is favourable to their forming new combinations... They are unscrupulous enough for anything."

His prediction proved true. That summer, some Tories began to float an idea that would have been unthinkable just months earlier. "Smarting over the Rebellion Losses Bill," as Brown's biographer J.M. Careless explains, "desperate over the state of commerce, some of them came up with an answer that confounded all past Tory tradition: nothing less than annexation to the United States."

It was a wildly unexpected twist. But the movement began picking up steam over the course of the summer. In Toronto, it attracted a smattering of support: our city would eventually get its own Toronto Annexation Association and a new local newspaper, The Canadian Independent, took up the cause. But it was in Montreal that the idea found its strongest support.

Montreal was the biggest city in Canada and had been hit particularly hard by the economic depression. Plus, it had a long history of tensions between anglophone Protestants and francophone Catholics. Many Montreal Tories blamed French-Canadians for the rebellions and for the arrival of Responsible Government; they saw the idea of joining the U.S. as a way to overwhelm French-Canadian culture and wipe it out.

Meanwhile, those ultra-conservative annexationists found unlikely allies: some of the most radical francophone Reformers wanted to join the States because they believed American institutions were more democratic and would discriminate against them less than the British had.

It was a strange and unexpected alliance that had the potential to redraw traditional political lines. And by the beginning of October, the leaders were ready to make a bold move: the publication of the Annexation Manifesto.

"To the people of Canada," it began with a burst of longwinded formality, "The number and magnitude of the evils that afflict our country … call upon all persons animated by a sincere desire for its welfare to combine … with a view to the adoption of such remedies as a mature and dispassionate investigation may suggest." The repeal of the Corn Laws, it argued, "has produced the most disastrous effects upon Canada. In surveying the actual condition of the country, what but ruin or rapid decay meets the eye?" Business was suffering, they claimed. So were the banks. The real estate market was grinding to a halt. "Commerce abandons our shores… This possession of the British Crown — our country — stands before the world in humiliating contrast with its immediate neighbours, exhibiting every symptom of a nation fast sinking to decay."

When they reached the climax of their argument — the proposed solution — they even switched to using all caps:

"THIS REMEDY CONSISTS IN A FRIENDLY AND PEACEFUL SEPARATION FROM BRITISH CONNECTION AND A UNION UPON EQUITABLE TERMS WITH THE GREAT NORTH AMERICAN CONFEDERACY OF SOVEREIGN STATES."

In other words, the Province of Canada should leave the British Empire and join the United States instead.

The manifesto sent shockwaves through the colony. The future of Canada suddenly seemed to hang in the balance. No one knew what would happen next, how much more support the idea would attract, how serious a threat it would prove to be. There were signs it might have traction. Some newspapers published supportive editorials. Resolutions were passed south of the border welcoming the idea. It was being treated as a serious proposal.

Plenty of Canadians, however, were horrified. The War of 1812 was still a living memory; many could recall bloody battles fought against invading American soldiers; they remembered towns looted and homes burned. The violence had driven a wedge between people living on either side of the border and helped foster a fledgling Canadian national identity. Most people weren't willing to abandon that growing sense of patriotism.

There were plenty of reasons for people in Toronto to oppose the Montreal manifesto. During the war, it had been occupied by American troops; property was pillaged, residents terrorized, buildings torched. Plus, while most Tories here were fiercely anti-Catholic, they didn't live side-by-side with French-Canadians in the way their counterparts in Quebec did. And our city wasn't hit as hard by the faltering economy. So, while a surprising portion of the Montreal establishment had thrown its support behind the manifesto, in our city it was a very different story. "The verdict of Toronto," according to historian Gerald A. Hallowell, "was clear and overwhelming in its repudiation of annexation." There was plenty of opposition to the idea across the province, but it was our city that would lead the charge.

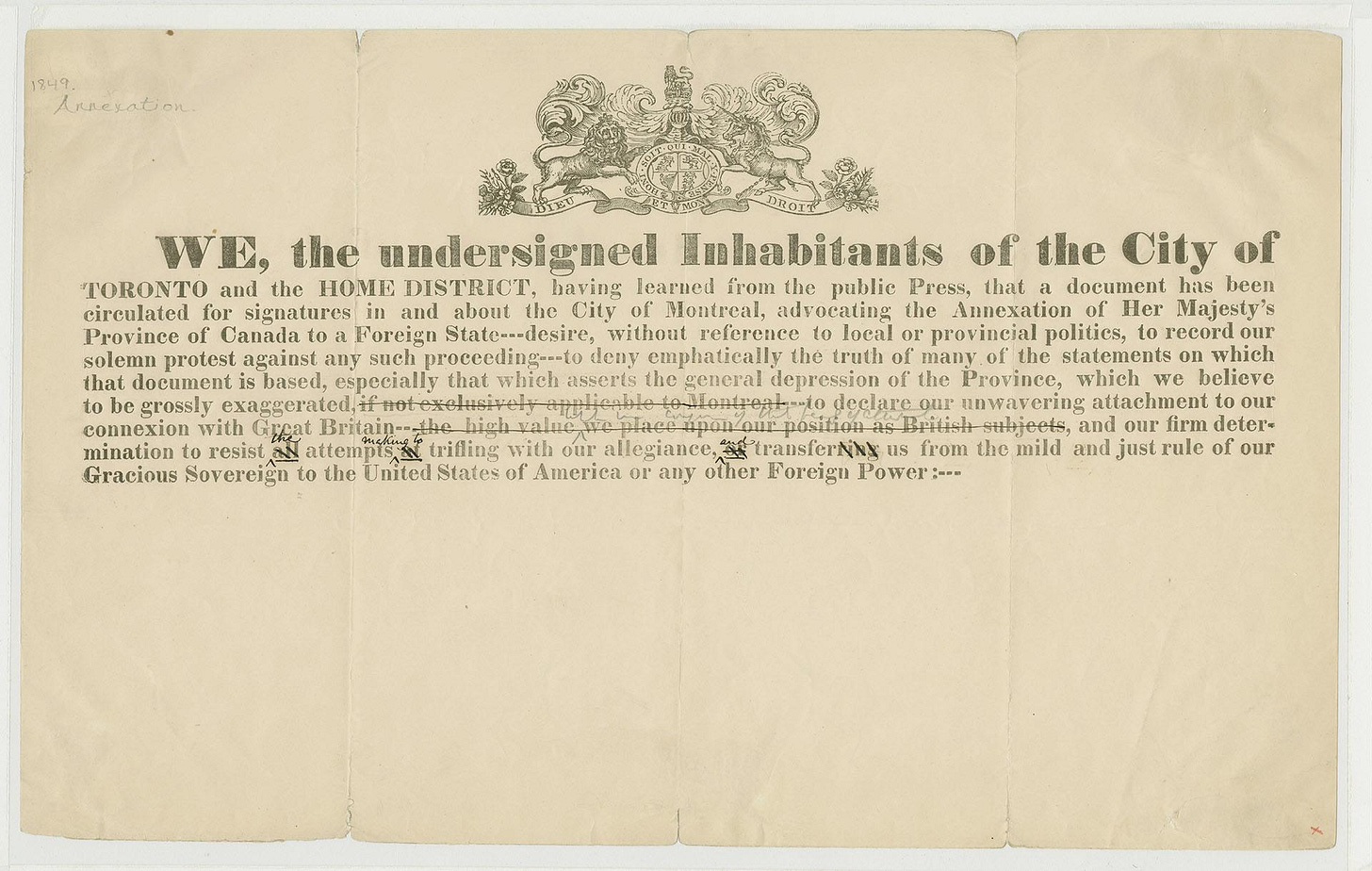

Toronto's political leaders leapt into action. The meeting at the courthouse was held just a week after the manifesto was published. It was attended by influential members of both parties, willing to temporarily set aside their differences in order to unite against annexation. They agreed to keep meeting every day at three o'clock for as long as they needed to. And while they didn't immediately agree on all the details, they were eventually able to negotiate the wording of their own proclamation: a counter-petition denouncing the idea of becoming part of the United States.

"We, the undersigned inhabitants of the City of Toronto and the Home District," it began, "in allegiance to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, do hereby solemnly protest against a movement recently made in the City of Montreal, for the annexation of the province to the United States of America."

Copies of the petition were left at banks, newspaper offices, and other prominent businesses around the city so members of the public could add their own names. The signatures came quick. Five hundred people had signed it by the end of the first day. Thousands more soon joined them.

The organizers and supporters of the petition included many of Toronto's most prominent citizens — politicians, business leaders, judges and lawyers — from both sides of the political divide. Tories and Reformers were now suddenly fighting for the same cause. The chair of the meeting was Sheriff William Botsford Jarvis, a leading conservative who'd fought against the rebels back in 1837. Henry Sherwood was a former mayor of Toronto whose followers had once murdered a Reform supporter, and who had personally taken part in at least one infamous riot himself. John Beverley Robinson was the leader of the Family Compact, the Tory clique that ran our city for decades. But those conservatives were now joined by their traditional enemies, including Robert Baldwin — the champion of Responsible Government whose administration had sparked angry riots just months earlier.

The most active opponent of annexation was another leading Reformer. George Brown was just thirty years old, but had already become one of the most influential members of the party. During the fight over Responsible Government, his house had been attacked by an angry Tory mob, his windows broken. Now, he used his newspaper, The Globe (which would later merge with others to become The Globe & Mail), to fight for Canada's future as an entity separate from the United States. The annexationist Tories, he declared had "gone demented" with "another piece of Montreal madness." For them, he said, "loyalty has a regular price, like a barrel of ashes, or a hundred weight of turpentine." He called for the firing of any government official who had signed the manifesto and denounced the plan as "treason." He wrote editorial after editorial after editorial passionately condemning the idea.

"The Globe," according to Careless, "would be given chief credit for checking the spread of annexationism in Upper Canada." But Brown wasn't alone. Other newspapers joined the fight. "The discussion of 'Annexation' is gall and wormwood to us," another Toronto paper, The British Colonist, announced, " The population of Canada is of a bold and independent spirit, insisting on its rights to form opinion for itself, and not easily enticed to desert its ancient and favorite ways." The Huron Signal agreed, "We are too proud of our national individuality to consent to be swallowed up, or become a mere insignificant integer of an unwieldy republic." The Dumfries Recorder denounced the movement as the work of "a few disappointed hack politicians [who] must be regarded not only as insane, but absolutely wicked, in every way injurious to the trade, credit and prosperity of the country." The Bytown Packet called the manifesto "contemptible." The Cornwall Freeholder went with "treasonable."

The opposition to the annexationists was swift and overwhelming. Even in Montreal, more people signed a counter-petition than added their names to the original manifesto. In the months to come, the movement would sputter as the economy began to recover. That autumn's harvest was a particularly good one. A new treaty eventually moved the Canadian colonies toward free trade with the United States. The annexation movement fizzled and died out.

As it did, its opponents celebrated. "We sincerely rejoice," The Ottawa Advocate wrote, "that the American eagle, lately brought into Montreal, has grown sickly, and is likely, very soon, to die ... A number of our friends have had guns ready to shoot him, had he extended his flight to Canada West [Ontario]."

Fear of the Americans, however, didn't vanish as support for the manifesto petered out. Over the next few decades, there would be plenty more talk of Canada being swallowed up by the United States. Many people south of the border still believed in the idea of Manifest Destiny — that the U.S would one day cover the entire continent. Those worries were only heightened by the outbreak of the American Civil War. Tensions along the border threatened to boil over. Abraham Lincoln's Secretary of State, William Seward, has been described as "an enemy of Canada" who repeatedly threatened annexation. American newspapers suggested the Canadian colonies would make a suitable replacement for the Southern states. In the wake of the war, a congressman even introduced a bill aiming to make annexation a reality. Soon, American armies really did invade: hundreds of Irish-American soldiers crossed the border in the hope of seizing Canadian territory so they could trade it back to Britain in return for Irish independence. None of it came to pass, but all of it kept fears of annexation alive.

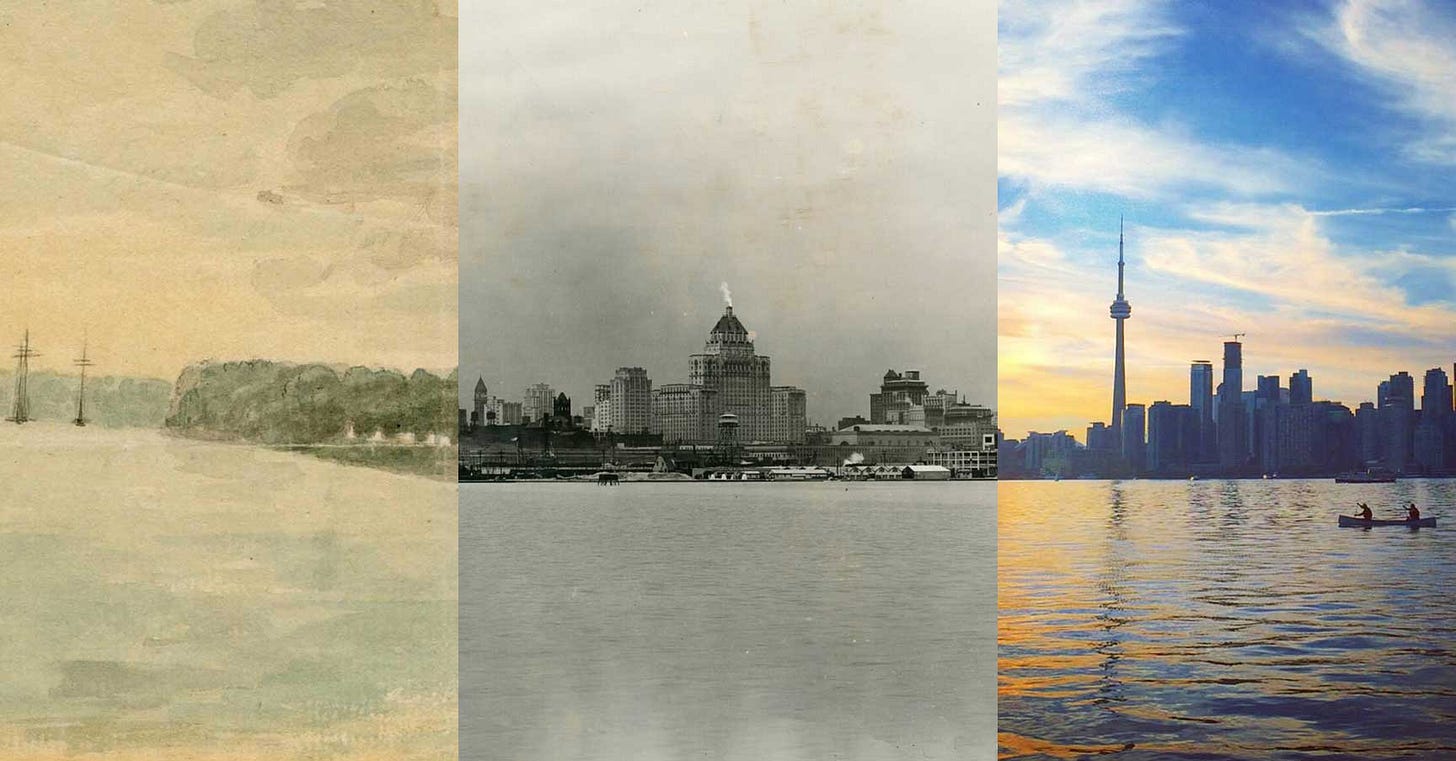

In the end, of course, Canadians would choose another path. As worries about an American invasion grew, political adversaries came together once again. This time, liberals and conservatives from the Province of Canada sailed down the St. Lawrence River to open talks with the other Canadian colonies about an idea they called Confederation. "Rest assured," Thomas D'Arcy McGee, one of the Fathers of Confederation, argued, "if we remain long as fragments, we shall be lost; but let us be united, and we shall be as a rock which, unmoved itself, flings back the waves that may be dashed upon it by the storm." Instead of becoming American states, the Canadian colonies would form their own country.

George Brown was at his desk the night it officially came to pass. The Globe's offices stood just a few doors down King Street from the spot where the anti-annexation meeting had been held on that rainy autumn day in 1849. The young Reformer who led the opposition to the manifesto had gone on to become one of the leading Fathers of Confederation. That night, he wouldn't sleep at all; he stayed up writing through the wee hours of the morning and well past dawn, penning a celebratory editorial filled with patriotic pride over the way Canadians had been able to set aside their differences. “This day the Dominion of Canada is proclaimed;" he wrote, "and, as Canadians [we] join hands, and a shout of rejoicing goes up from the four millions of people who are now linked together for weal or for woe."

Canada would still have plenty of problems. There would still be prejudice and discrimination, political rivalries and scandals, suffering and hard times. But those problems would be Canadian problems, to be wrestled with and solved ourselves. Canadians had said no to becoming part of the United States, over and over again. We would be in charge of our own future.

As the clock struck midnight on July 1, 1867, the celebrations began. Outside George Brown's window, the bells of St. James Cathedral rang out over King Street. Drunken crowds spilled out onto the road, singing patriotic songs. And high above the city, fireworks lit up the night sky.

If you’d like more about the (often tense) history between Canada and the United States, some of the most popular episodes of our CANADIANA documentary series are about exactly that — and you can watch them for free on YouTube.

Last year, we released the first in a two-part series about the Canadian connections to the American Civil War. (Part Two will focus more on how the Civil War helped drive the push for Confederation, as well as Canadians who supported the Confederacy.)

Our most-watched episode ever is about how fears of American invasion in the wake of the War of 1812 led to the construction of the Rideau Canal:

And we’ve also got an episode about the highway built across the Canadian north by the American military during the Second World War:

Thanks so much to everyone who has sent me kind words about the newsletter’s new name — and to those of you who have made the switch to a paid subscription! It’s only thanks to the heroic 4% of readers who support the newsletter with a paid subscription that The Toronto History Weekly The Toronto Time Traveller is able to survive. If you’d like to make the switch yourself, you can do that right here:

“From Hogtown To Downtown” With The LIFE Institute!

I’m kicking off the new year by bringing back my most popular course — and this time it’s thanks to the LIFE Institute!

From Hogtown To Downtown: A History of Toronto in Eight Weeks is an overview of the history of our city. And I’m thrilled to be offering it through the LIFE Institute, which provides educational programming for “older adults” (50+) and is affiliated with Toronto Metropolitan University’s G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education.

Description: The history of Toronto is filled with fascinating stories that teach us about ourselves and our community. In this eight-week, online course, we'll explore the city's past from a time long before it was founded, through its days as a rowdy frontier town, and all the way to the sprawling megacity we know today. How did Toronto become the multicultural metropolis of the twenty-first century? The answer involves everything from duels to broken hearts to pigeons.

When: Tuesdays at 12:30pm from January 28 to March 18.

Where: Online over Zoom.

How Much: $99 with a membership.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE LIFE INSTITUTE

LEARN MORE ABOUT CURRENT COURSES, INCLUDING MINE

Talking About the Romantic History of Toronto!

A new talk announcement! In the lead-up to Valentine’s Day, I’ll be sharing stories about The Toronto Book of Love and the romantic history of the city thanks to the Town of York Historical Society. And it will be happening at Toronto’s First Post Office — which, if you haven’t been before, is a wonderful little space with a fascinating history.

“Join local author and historian, Adam Bunch as he presents his acclaimed publication, "The Toronto Book of Love" and explore Toronto's history through true tales of romance, marriage, passion, heartache, lust, and the scandalous love affairs of the early city. Learn how Toronto has been shaped by crushes, jealousies, and flirtations as told by the author himself. Spots are strictly limited and pre-registration is required.”

When: Friday, February 7 at 7pm.

Where: Toronto’s First Post Office.

How Much: $17.31 for members; $22.63 for non-members.

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

INVASION NEWS — Jamie Bradburn looks back at the day the Americans invaded Toronto (still the town of York back then) during the War of 1812. Read more.

MUSEUM NEWS — Matt Elliott (whose invaluable City Hall Watcher newsletter you’ll find here) gives us an update on Bluesky about the dream of a Museum of Toronto at Old City Hall: “staff say work stalled out during the pandemic.”

(Click to open on Bluesky.)

FORTS & MONUMENTS NEWS — He also mentions another couple of heritage-related projects that are still in search of funding: “upgrades at Fort York to reconstruct more historic buildings” and “funding to maintain monuments at the Guild.”

(Click to open on Bluesky.)

TOURIST IN YOUR OWN CITY NEWS — Anne Vranic, the History Hype Girl on social media, was on Breakfast Television last week to talk about some of our city’s underappreciated architectural gems. Watch it.

SINUOUS NEWS — In The Globe & Mail, Alex Bozikovic takes a look back at the construction of the AGO’s Henry Moore Sculpture Centre half a century ago and how it informs the gallery’s upcoming expansion. “It carries a lesson from the past: Architecture can change a city, but it can also disappear. Art abides.” Read more. (Paywalled.)

MORE POWER NEWS — Bozikovic also writes about the debate over the big new plan for the site of the old Hearn Generating Station in the Port Lands, which I mentioned last week. One one side of the argument: “Does every important site in Toronto need to have condos on it? In this case, the proponents are the Cortellucci family, powerful suburban developers and allies of Ontario Premier Doug Ford.” On the other: “What would government do with this place? Toronto in 2024 shows zero capacity for building new public institutions or major public buildings. The city can’t even figure out what to do with Old City Hall.” What’s clear, he writes, is that “The Hearn can be a great place. And if Toronto wishes to reach its potential as a city, it has to be.” Read more. (Paywalled.)

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

NEWSGIRLS: GUTSY PIONEERS IN CANADA’S NEWSROOM

January 22 — 6:30pm — Don Mills Library

“Toronto author Donna Jean MacKinnon documents the lives of leading female reporters who began their careers during newspapers' Golden Age (1920-1960). Her fascinating presentation recounts how these trailblazers covered every beat from art, fashion, and crime to social issues and politics.”

Free with registration!

55+ TEA TIME: DIGGING DEEP INTO RUNNYMEDE’S HISTORY

January 23 — 1pm — Lambton House — Heritage York

“Local historian/author Jim Adams has been researching the history of one of west Toronto’s smallest neighbourhoods, Runnymede. He is documenting its geographic, cultural, business and residential history. Join in a lively quiz and learn about his first graphic little book about local war hero Fred Topham.”

Free for people 55+

ILLUMINATING THE NIGHT: THE MAGIC LANTERN SLIDES OF WILLIAM JAMES & THE HISTORY OF TORONTO

January 23 — 7pm — Toronto’s First Post Office – Town of York Historical Society

“Join Richard Fiennes-Clinton as he discusses William James, the notable Toronto photographer who took thousands of images of the City in his career spanning several decades. Richard will discuss how James often made his images viewable to the people of Toronto by displaying them on his "magic lantern", a projector that used kerosene for the power of illumination and hand-tinted dozens of theses slides. William James and his luminary slides will be the subject of this presentation bringing light and colour to this often darker and wintry time of year.”

$22.63 for non-members; $17.31 for members.

CURATORIAL TOURS OF BLACK DIASPORAS TKARONTO-TORONTO

January 25 & February 22 — 1 & 3pm — Museum of Toronto

“Join us at Museum of Toronto for a curatorial tour of the Black Diasporas Tkaronto-Toronto exhibition. Led by a member of Museum of Toronto, you’ll get a behind-the-scenes look at this exhibition while learning about the importance of oral histories and community archives.”

$10 recommended admission.

THE HOWLAND LECTURE

January 26 — 2pm — Lambton House — Heritage York

“Howland Lecture with Darin Wybenga, Heritage Interpreter for the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation on the Mississaugas and the Humber.”

Free, I believe!

TORONTO’S FORGOTTEN DAILIES & THE COLOURFUL PERSONALITIES BEHIND THEM

January 28 — 7pm — Online & in person at the Ralph Thornton Community Centre — Riverdale Historical Society

“Mr. Bradburn's presentation will share the stories of three daily Toronto newspapers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that, though largely forgotten now, played an important role in the life of the city: The Mail/Mail and Empire; the News; and the World. These papers were political battlefields, were involved in major labour issues of the day, had colourful owners, and introduced some of Toronto's first major newspaper columnists.”

$5

Wonderful account of events of which I, lifelong Canadian, had bee unaware. Thank you! And let's hang in there, OK?

Fascinating, especially given Trump's current annexation chatter. We defeated it then and we'll defeat it now.