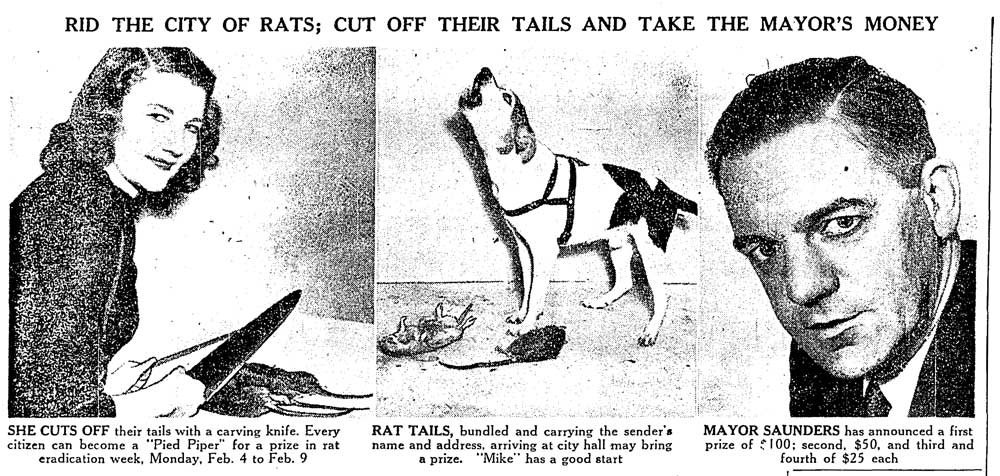

When People Mailed Rat Tails To City Hall

Plus a scandalous tour of Old Toronto, letters from the front, and more

The packages began to arrive in the winter of 1946. They came to City Hall, where a reluctant civil servant had been given the grisly task of opening them. Inside, he found a gruesome harvest: scores of dismembered rat tails. The rodents had been killed by the people of Toronto, the tails chopped off and then mailed in to City Hall at the request of the mayor. One of the weirder chapters in the history of our city was underway. Rat Eradication Week had begun.

The pesky rodents were a relatively new problem in North America. When Toronto was founded in the late 1700s, rats had only been living on the continent for about twenty years; they’d come over on ships during the American Revolution. It’s hard to say exactly when the first rats arrived in our city. But they seem to have been well established by the middle of the 1800s. And as the town grew, so did the rat problem.

By the early 1900s, Toronto’s newspapers were with filled with disturbing reports from all corners of the city. There were stories of rats attacking children in their sleep. Of rats chewing through pipes. Of rats gnawing away so loudly it kept people up at night. In Cabbagetown, they were said to be “as big as cats.” In Etobicoke, they were “big enough to put saddles on.” At the municipal abattoir, they came “in platoons, battalions and regiments.” Big numbers of them roamed the waterfront every year after the CNE. When the Don Valley flooded one spring, thousands of rats scrambled up the slopes as people gathered on nearby bridges to watch. At Eastern Commerce high school, students complained rats were eating their books. “They come right into the portable room and hold public meetings and banquets.”

Torontonians had been fighting a losing battle against the rodents for generations. Traps were set. Bait laid out. Trails of toxic dust put down so the rats would walk through it and then lick it off their paws. Poison gasses originally developed for use in the trenches of the First World War found a new enemy in the rat holes of our city. At the grain elevators on the Esplanade, a dozen cats were kept on staff. At old Union Station, a ferret was given the run of the yard — the weasel-like animals were a popular method of rat control a century ago, long and skinny enough to follow rats into their burrows.

At the Riverdale Zoo (now Riverdale Farm), all those methods were tried — a campaign of death that lasted decades. But it was some of the zoo’s own residents who had the most notable success: a golden eagle, a big griffon vulture, and the snowy owls all feasted on the rats that plagued the place. And wild birds of prey were lauded by Toronto’s newspapers as vital allies in the war against vermin. A century ago, they were considered pests themselves — often shot on sight thanks to an overblown reputation for killing farmers’ chickens. Even the snowy owls who came south to winter on the islands were targets for hunters. The press repeatedly published pleas to spare the birds, highlighting the role they played in killing the rats who infested the island’s cottages in the off-season. There were so many rodents out there not even a colony of feral cats was enough to keep them under control.

On the waterfront, it was a rat-hunting dog making headlines. Toronto’s shoreline was being moved further south, with garbage and rubble used to fill in the lake. That rubbish attracted rats in droves. Along the southern edge of the Exhibition Grounds, where the land was being extended for the construction of Lake Shore Boulevard, thousands of rats lived in holes along the bank. You could see the paths the creatures carved through the grass. And it was there in that fertile hunting ground that a little black and white fox terrier spent his mornings at work.

According to The Globe, the mysterious dog would arrive every morning at 7am — as promptly as if he were reporting to his place of business. Then, he would proceed to spend his morning digging the rats out of their holes and chasing them down. The Park Superintendent told the paper he’d seen the dog kill twenty-four in a single hour. And when the local garbage collector eventually passed by on his daily rounds, the terrier would know it was time to clock out and head off home — only to return at the very same time the next morning.

And yet, even after all those decades of effort, the rats of Toronto didn’t seem to be going anywhere. They were said to be too fertile, too smart and too resilient to defeat. Newspapers reported that a single pair of rats could produce 359,000,000 descendants within three years. They claimed they were the smartest of all animals — more intelligent than apes or crows or dolphins — much too clever to be tricked. And they had a reputation for being tough, too. “When you corner a rat,” the chairman of the Parks Committee explained, “you have cornered something that can give one of the stiffest exhibitions of the fighting spirit outside of the wrestling shows at Maple Leaf Gardens.”

Plus, there were legal limits on what could be done to combat them. While many individual Torontonians had no problem killing the critters in creatively cruel fashion — even Humane Societies debated whether rats really counted as animals at all and deserved any legal protection — there were obstacles to larger scale operations. The municipal government didn’t have the power to crack down on all the rats’ breeding grounds. When a rat-infested lumber pile was discovered near Mount Pleasant Cemetery, for instance, the City told residents nothing could be done because they only had jurisdiction over rat-infested lumber piles found indoors. Without a roof, they were helpless. And so, the responsibility for fighting rats was generally left to individuals rather than the authorities.

But that was about to change. The rat problem had only gotten worse over the course of the Second World War. By the end of 1945, at least a million rats were thought to live in the city — more than twice the number of people. And while that may have been an exaggeration, the large numbers of rodents who did live here were hard to miss. They were said to cost Toronto millions of dollars every year. City Hall could no longer ignore the issue. The rats were right on its doorstep. In fact, they’d invaded the building itself.

City Hall was full of rats. The police officers who kept watch over the jail cells in the building (which we now call Old City Hall) had to hang their lunches from coat hooks to keep them away from the hungry rodents. And there were even more rats just outside. City Hall was right next door to the neighbourhood known as Toronto’s most notorious “slum.”

The Ward had been run by predatory landlords for decades; they forced tenants to live in terribly unsanitary conditions, creating an environment where rats could thrive. Local politicians reported that some people in the neighbourhood were afraid to go to sleep. The principal of a nearby school said children had been coming to class with bandaged fingers, having been bitten overnight. The kids kept their lunches in metal tins so the rats couldn’t eat them.

City Councillors representing the Ward had been calling for a campaign against the rodents for years. One had long been advocating for the City to create an anti-rat week, hoping it would help raise awareness and cut down on their numbers. And while his idea made him a target for tongue-in-cheek newspaper columnists looking to poke fun, he would eventually get his way.

In February 1946, the mayor finally took action. He announced a “Rat Eradication Week,” one of the most bizarrely gruesome initiatives in our city’s history. He called on Torontonians to kill as many of the rodents as they could, then to chop off their tails, package them up, and mail them in to City Hall where the Medical Officer of Health would be forced to tally them up. The winners would be rewarded with $300 in prize money — the equivalent of thousands of dollars today.

“The number of rats in Toronto has reached the point where they constitute a menace,” Mayor Leslie Saunders explained. “Rats are responsible for more deaths than are known… We must wipe them out if possible. So with this as our aim, I call upon every citizen of Toronto to take an active part in this drive… Set traps, use poison, use every means at your disposal to kill the pests. Overlook nothing… We must all cooperate now before it is too late.”

The contest was won by a man from South Riverdale; Gordon Lambert mailed in 162 tails. And while Rat Eradication Week proved to be a one-time affair, in the years to come the City would keep up the fight. The next mayor launched “the greatest rodent control campaign ever known to Canadians.” An Anti-Rat Squad was formed to hunt the rodents down. There were crackdowns on overflowing garbage bins, junkyards, dumps, and unsanitary butcher shops. The Citizens Voluntary Rodent Control Committee was formed and the Medical Officer of Health called on everyone to do their part. “Tell them to kill a rat a day,” he told the press. Soon, more than a thousand rats were being killed by the City every month. “When we've finished,” the head of the initiative boasted at its launch, “we'll have fed a poison blue-plate special to every rat in the entire City of Toronto. And the banquet begins right now.” New legislation followed, giving the municipal government the powers it needed to truly tackle the problem. Rats would always have a home in the city, but the people of Toronto finally seem to have gotten the upper hand on their fuzzy neighbours.

Although, as you walk the city streets today, passing one overflowing garbage bin after another, you could be forgiven for wondering whether the future of Toronto’s rats might be looking up once again.

Thanks so much to CBC Radio producer Brendan Ross for sparking this week’s story idea by asking me to share some rat tales on Metro Morning a couple of weeks ago. You can listen to three of those segments here…

The Rat-Hunting Terrier of the Lake Shore

I’ll save the fourth segment for next week’s newsletter, when I’ll be sharing one more rat tale from Toronto’s past: the story of old Union Station and its resident rodent ghosts.

We’ll also be talking about the history of Toronto rats as part of….

A VERY GROSS HISTORY OF TORONTO

My new online history course kicks off on November 22 and will be filled with icky stories like Rat Eradication Week! Here’s the full course description:

Ewww. Sure, Toronto has a reputation for being a remarkably clean city. But it also has a long history of being a filthy, disgusting mess. From its days as a muddy frontier town with mysteriously green puddles collecting in its streets to hordes of rats swarming the slopes of the Don Valley, we'll spend four lectures digging into some of the ickiest, smelliest, slimiest stories Toronto history has to offer. And we'll learn a lot about our city and how it works in the process.

A SCANDALOUS TOUR OF OLD TORONTO

I’ve been having a ton of fun leading some historical walking tours over the last few months; they’ve been a big success and the response has been absolutely wonderful. So I’m planning to sneak a couple more in before the end of the year. First up…

A Scandalous Tour of Old Toronto!

There are plenty of skeletons in our city’s past; Toronto’s history is filled with tales of dishonour, disgrace and disrepute. On this walk through the city’s oldest neighbourhoods, we’ll uncover some of those notorious scandals. From deadly duels to lustful brothels, from bribery and corruption to incest and infidelity… there are shocking tales to be told about the history of Toronto.

Saturday, November 26 — 3pm

Meet at the corner of Parliament & Mill Street (the western entrance to the Distillery District)

The tour will last about an hour and a half and finish near Yonge & King

Pay what you can

Before we continue, just a very quick reminder that The Toronto History Weekly will only survive if enough of you are willing to switch to a paid subscription. Only about 5% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 20 other people. You can make the switch by clicking here:

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

LETTERS FROM THE FRONT NEWS — Toronto History Weekly subscriber Leilah Ambrose tipped me off to an extraordinary project this week. “Letters Home” shares letters written by Canadian soldiers during the First and Second World Wars, mapping them out according to the addresses to which they were sent. That means you can see for yourself whether one of the heartbreaking letters was sent to an address near where you live. Explore the map.

ROW BY ROW NEWS — Library & Archives Canada tweeted about a particularly meaningful item in their collection. It’s an original copy of the first magazine to print “In Flanders Fields,” written by University of Toronto graduate John McCrae:

ARMISTICE NEWS — Katherine Taylor dug into her archives to share the story of what happened when Torontonians poured into the streets on Armistice Day to celebrate the end of the First World War. Read more.

130 YEARS OF THE STAR NEWS — The Toronto Star marked its 130th birthday by having Jim Coyle sharing 130 memories from the paper’s history. Read more.

TEACHER STRIKE NEWS — Another timely piece: Over at TVO, Jamie Bradburn dug into the story of a teachers strike in Ontario back in 1973. Read more.

MOVING SHORELINE NEWS — And here’s a nifty one tangentially related to my rat story above. Victor Caratun recently shared a pair of neat “then & now” images that highlight the changes to Toronto’s shoreline. You can see just how close the lake used to be to the Esplanade. It’s right there in the background of the first photo:

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

TWO WAYS TO WRITE HISTORICAL TORONTO

November 14 — 7pm — Another Story Bookshop

“Jane Cawthorne’s debut novel, Patterson House, is set in the Beach between 1850 and 1954. Historian Katherine Taylor’s photographic history, Toronto: City of Commerce 1800-1960, nominated for the Heritage Toronto Book Award, traces the ever changing commercial landscape of Toronto and recounts the stories of vanished businesses and their owners and workers. What goes into writing the history of a place? Both Jane and Katherine will read from their work and, in conversation with MC Judy Rebick, will discuss these two very ‘Toronto’ books.”

Free!

RITA LETENDRE: CELEBRATION OF LIFE

November 23 — 7pm — AGO

“Born in Drummondville, Quebec to Abenaki and Québécois parents, Rita Letendre began painting in 1950s Montreal, when she associated with Quebec's prominent abstract artist groups Les Automatistes and Les Plasticiens. After living in Europe and the U.S., she moved to Toronto in 1969. Seeking to express the full energy of life and harness in her powerful gestures an intense spiritual force, Letendre worked with various materials including oils, pastels and acrylics, using her hands, a palette knife, brushes and uniquely the airbrush. Renowned for her bold and visceral style, she pushed the boundaries of colour, light and space to new heights. Her work embodies her ongoing quest for connection and understanding. The free event will include a screening of interviews with Letendre, alongside remembrances by her colleagues, friends and family.”

Free with registration.

AUTHOR TALK: THE BEATLE BANDIT WITH NATE HENDLEY

November 24 — 7pm — Toronto Public Library’s Brentwood branch

“Winner of the Crime Writers of Canada Award of Excellence for Non-Fiction 2022, true crime writer Nate Hendley tells the story of Canadian bank robber Matthew Kerry Smith, aka the Beatle Bandit. The sensational true story of how a bank robber killed a man in a wild shootout, sparking a national debate around gun control and the death penalty.”

Free!

MOST HOPES: HOMES & STORIES OF TORONTO’S LOST WORKERS

November 29 — 6:30pm — Online — Riverdale Historical Society

“RHS welcomes Leslie Valpy, a heritage conservationist practitioner and Don Loucks, a Heritage Architect, to speak about their recent book, ‘Modest Hopes, Homes and Stories of Toronto’s workers from the 1820s to the 1920s’, which celebrates Toronto’s built heritage of row houses, semis, and cottages and the people who lived in them. Toronto’s workers’ cottages are often characterized as being small, cramped, poorly built, and in need of modernization or even demolition. But for the workers and their families who originally lived in them from the 1820s to the 1920s, these houses were far from modest. Many had been driven off their ancestral farms or had left the crowded conditions of tenements in their home cities abroad. Once in Toronto, many lived in unsanitary conditions in makeshift shanty-towns or cramped shared houses in downtown neighbourhoods such as The Ward. To then move to a self-contained cottage or rowhouse was the result of an unimaginably strong hope for the future and a commitment to family life.”

Free, I believe!

AN ILLUSTRATED TALK ON THE HISTORY OF ADELAIDE STREET

November 30 — 7:30pm — Online — North Toronto Historical Society

“Once home to upscale residences and important public services, Adelaide Street's buildings later housed light industries such as publishing. There are still examples of the detached and row housing that dominated west of Yonge in the late 1800s. The financial district extends to Adelaide and the condo scene here is ever-changing. Architectural historian and NTHS member Marta O'Brien will present an illustrated talk on the history of Adelaide Street.”

Free with registration, I believe.

DEATH OR CANADA

December 1 — 7pm — Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Dr. Mark G. McGowan will speak about his most recently published book, Death or Canada: The Irish Famine Migration to Canada, 1847, and his exploration of this migration's impact on Toronto. ‘Historian Mark McGowan delves beneath the surface of statistics and brings to light the stories of men and women who had to face a desperate choice: almost certain death from starvation in Ireland, or a perilous sea voyage to a faraway place called Canada.’”

$22.23 for non-members; $16.93 for members.

RESEARCHING THE HISTORY OF YOUR HOUSE

December 1 — West Toronto Junction Historical Society

“Is there something unique about your home or neighbourhood that you’ve always been curious about? How old is my home? Who lived there in the past? Jessica Algie, from the City of Toronto Archives, will show you, step by step, how to research a Toronto property using archival collections including fire insurance maps, city directories, historic photographs and tax assessment rolls. Join Jessica on a journey to uncover the story of one interesting home in the West Toronto Junction neighbour hood. Then, apply those research techniques to your own home!”

AUTHOR TALK: THE BEATLE BANDIT WITH NATE HENDLEY

December 3 — 11am — North York Central Library

“Toronto author Nate Hendley offers a presentation based on his book, The Beatle Bandit: A Serial Bank Robber's Deadly Heist, a Cross-Country Manhunt, and the Insanity Plea that Shook the Nation. On July 24, 1964, Matthew Kerry Smith put on a Halloween mask and a "Beatles" wig and robbed a bank near Toronto to fund a one-man revolution against the government. This murderous heist fueled a nationwide debate about guns, insanity pleas, and the death penalty. The Beatle Bandit, winner of the Crime Writers of Canada 2022 Award of Excellence for Non-Fiction, details this strange story.”

Free with registration!