The Wreck of the Anna Bellchambers

Plus a new online course, a grisly thank you event, and more!

A storm is raging. As dawn breaks over Toronto on a dark and grey October day in 1873, the wind has already been howling for hours, the waters of Lake Ontario whipped into towering waves that crash upon the shore. It must be miserable for the construction crew working on a steam-powered dredge far out on the other side of the islands, digging a channel for a water pipe as the storm continues to blow. It's important work. The city has been ravaged by deadly outbreaks of disease caused by the sewage-tainted drinking water of the harbour; the new pipe will reach out farther into the lake to provide Torontonians with water less likely to kill them. But on this particular morning, that work will have to wait. A much more urgent crisis is underway.

It was sometime after seven in the morning, as the black night faded into dreary day, that the dredge crew spotted it: a ship out near Gibraltar Point, clearly in distress, trapped by the sand and nearly capsized, battered by the storm, besieged by wind and waves. The Anna Bellchambers was in trouble. Two lives had already been lost. But there was still one left to save.

The dredge crew leapt into action.

A century and a half ago, the waters of Toronto were a dangerous place to sail. When the city was founded in the late 1700s, there was only one entrance into the bay: the Western Gap, lined by threatening shoals hidden beneath the surface of the water. In fact, that's one of the reasons Toronto was built here in the first place. The natural bay made the town easy to defend in case of an American attack. But it also meant that for much of the city's history, sailing in and out of our harbour could be a harrowing experience.

The Anna Bellchambers was familiar with those dangers. The ship had been built a decade earlier by an innkeeper in Pickering. The schooner is thought to have been named after his wife and sailed out of Frenchman's Bay, joining the fleet of small vessels that supplied our city with fuel. By then Toronto had begun its transition to coal power, but it was still largely run on wood. Huge mountains of cordwood were piled on the waterfront wharves, shipped in to power our city's steamboats and trains, and to keep our homes warm. The Anna Bellchambers was a regular visitor. Its crew would load it up with as much wood as it could carry, so heavy and low in the water that the waves would wash across its deck as it made the slow journey west to Toronto.

This time, the schooner had left Pickering on a late October afternoon, weighed down by yet another heavy load. It was a short trip, but it still took hours; it was well after dark by the time the ship approached our harbour. Captain William Edwards must have been at least a little bit nervous. He planned to sail into the bay through a new and potentially treacherous entrance. When Toronto had been founded eight decades earlier, the islands weren't islands yet — they were still connected to the mainland. It was only in the 1850s that a series of powerful storms broke through the peninsula, cut the islands off from the mainland, and opened the Eastern Gap. Even now, in 1873, there was only a thin and winding route through the sand. There was no lighthouse, no concrete piers. It was not an easy passage — especially on a dark and stormy autumn night.

Twice before, the Anna Bellchambers had nearly been wrecked as it tried to make its way into the harbour. On both of those previous trips, rough waves had begun to fill its hold with water. Emergency crews had been forced to rush to the ship's aid, rescuing the sailors and saving the schooner by pumping the water out before it could sink. So, Captain Edwards was well-aware he needed to be cautious. He sent one of his men — Thomas Mansfield — out in a rowboat, armed with red lanterns to hang on the buoys that marked the entrance to the bay.

That's when things began to go wrong.

Mansfield couldn't find the buoys in the darkness. And with the wind picking up, he overshot his mark and found himself fighting the waves inside the bay, trying to row back toward the schooner but getting pushed farther and farther away, heading backwards toward the mainland instead. He was eventually forced to give up, heading into the city to wait for the rest of the crew to arrive.

The Anna Bellchambers was on its own. And now the storm was gathering strength. As the wind blew and blew, the ship was getting pushed out to the west, away from the Eastern Gap. Captain Edwards eventually gave up on that approach altogether and decided to go the long way around instead. He would sail his ship past the islands, around Gibraltar Point, head alongside what's now Hanlan's Point Beach, and come in through the Western Gap instead.

The Gibraltar Point Lighthouse has kept watch over our waters for more than 200 years. Today, it's the oldest lighthouse on the Great Lakes, the second oldest anywhere in Canada, and the oldest building in Toronto still standing on the spot where it was originally erected. Built to safely guide ships around the dangerous shallows that surround the islands, it has born silent witness to countless tragedies — from the murder of the city's first lightkeeper to the countless ships wrecked on our shores despite the lighthouse’s beacon. And on this stormy October morning, it would witness yet another.

It was when the Anna Bellchambers reached Gibraltar Point that things began to spiral out of control. The waves were now so big, they were crashing over the side of the vessel, swamping the decks, filling the hold. The small crew rushed to throw their wooden cargo overboard, but it was too late. The ship tilted way over to one side, nearly capsizing, in danger of running aground. The captain dropped anchor, trying to keep his ship afloat, but with the schooner pitched over to one side, the chain wasn't long enough to reach the lakebed.

By now, it was three in the morning. And as the wind and the waves kept up their assault, Captain Edwards knew he was running out of options. He was in danger of being swept overboard — and so were the other two remaining crew members, including his fourteen-year-old son, Joseph. "The only chance we had to save ourselves," he would later explain, "was to lay hold of the rigging... Finding a piece of line floating about, I lashed myself to the rigging, and tied my son … to my body." The father took hold of his boy and hung stubbornly from the ropes, hoping they'd live long enough to be rescued.

The final crew member, Peter Young, did the same. He was a veteran sailor, 45 years old. But he must not have tied himself in quite as tightly. Twice, the waves washed him off the rigging and twice he struggled back into place. When a third wave came, he was washed away yet again. This time for good. He disappeared into the lake, swallowed up by the storm, drowned.

Captain Edwards clung on. Hour after hour, he and his son hung there in the rigging as the tempest raged around them, pounded by frigid waves, lashed by cutting winds. Decades later, The Toronto Telegram would describe the scene, seeming to take a bit of poetic license. According to them, Captain Edwards reassured his boy as they watched the beacon of the lighthouse spinning through the chaos of that cold October night. "Bear up, Joe; it won't be long before daylight and they'll see us and take us off like they did the last time. It'll soon be light now, boy! It'll soon be light now!"

But those were long hours. And the captain's strength was failing. He would soon slip into unconsciousness. "Before I lost my senses," he remembered, "my son asked me if I was afraid to die, saying that he was not, and that he knew he was going to die, as he was so cold."

It was nearly five hours before dawn broke and the Anna Bellchambers was finally spotted by the dredge crew. A few of the workers jumped into a skiff and rushed to help, rowing as fast and as far as they could before the storm forced them ashore; then they hurried along the wet sand until they were as close to the stranded ship as they could get. It was out there in the water, still a few hundred metres from shore. But from where they were standing, they could make out the two figures lashed to the rigging. They called out to them, asked if they could throw a line toward the beach. But even if the captain heard them over the roaring wind, he was in no shape to help. They'd have to find another way.

The crashing waves made it impossible to swim, so they'd need to find a boat — something strong enough to survive the storm. First, they tried the lighthouse. But the lightkeeper, George Durnan, had already seen the Anna Bellchambers and made his own rescue attempt. He and another man risked their lives trying to reach the ship, but their small boat had been no match for the tempest. They'd only gotten close enough to see someone on board wave for help before they were pushed back toward shore.

So, the dredge crew raced off in search of our harbour's most famous hero. They headed for William Ward’s house.

No one has had more experience saving lives in the waters of Toronto than William Ward. His father had begun his career by fishing the frigid North Sea before leaving England for the Canadian colonies. He'd built a small cottage on the Toronto islands in the 1830s, back before they were islands. As Mary Jane Fairburn writes in Along The Shore: Rediscovering Toronto's Waterfront Heritage, David Ward made his living by catching fish in the lake beyond the sandbar. He'd learned from local First Nations fishermen — whose ancestors had been hunting in those waters for thousands and thousands of years — that by climbing the trees along the shoreline he could get a good view of where the schools of herring were swimming.

David Ward's descendants would live on the islands for generations; they're still remembered in the name of Ward's Island today. But the waters of Toronto Bay could be dangerous even for them. And when young William was just fourteen years old, tragedy struck. He took his sisters out for a leisurely Sunday sail, but as they headed home, a strong spring breeze kicked up. A violent gust caught the sail and the boat tipped over, spilling William and all five of his sisters into the water. They struggled to right the boat and climb back aboard, but just as they did… another gust sent them right back into the waves. William managed to save himself, but his sisters — weighed down by their wet Victorian dresses — weren't as lucky. He watched, horror-stricken, as Jane, Mary Ann, Cecilia and Rose Ellen all drowned. Phoebe was the last to go, clinging to the side of the boat as long as she could before slipping beneath the waves.

William Ward would spend the rest of his life trying to make up for it.

His first rescue attempt came just six years after his sisters drowned. When a schooner called the Jane Ann Marsh got caught in a terrible blizzard, Ward and a champion rower, the Black oarsman and boxer Richard Berry, raced out through the blinding snowstorm. They had to chip the crew out of the rigging where they'd been frozen in place by the ice, bringing them back to shore two by two until every sailor had been saved. It was the beginning of a life dedicated to keeping our waters safe, filled with one dramatic rescue after another. By the time Ward died in the early 1900s, he was credited with saving more than 160 lives.

But even William Ward had his limits. On that October morning in 1873, the waves were just too big. There was no way his small boat would be able to withstand the punishment of the surf long enough to reach the Anna Bellchambers and rescue those on board. In decades to come, newspapers would give dramatic accounts of his heroics that day — claiming he'd fought snow and ice to reach the floundering vessel. But in truth, the storm was too great; there was no help he could offer.

And he wasn't alone. While the dredge crew had raced down to Ward's house, it seems the lighthouse keeper, George Durnan, had also rushed off looking for help. He headed for Thomas Tinning, commander of the Toronto Harbour Commission's lifeboat. Tinning was no stranger to dramatic rescues himself — more than once he'd risked his own life to save the crew of a sinking vessel. But he'd spent the last hour trying to convince other sailors to join him in mission to save the Anna Bellchambers — to no avail.

Still, the dredge crew wasn't about to give up. They rushed back along the island toward the ship, finding that the storm had pushed it closer to shore. Charles Colman decided it was now near enough to risk it. He took off his jacket and waded out into the wild surf, fighting his way through to the ship. He managed to get a hold of it, briefly, only to be flung back into the water by the force of a breaking wave. But with a second effort, he hauled himself aboard and began to make his way over to the rigging where the captain and his son were waiting.

Captain Edwards was half-conscious as Colman approached; he pointed to his son and tried to speak — but no words came. And with that, it seems, he passed out again. Later, he wouldn't remember how the rescuers cut him down from the rigging and tied a rope around him, how they pulled him through the waves to the beach and took him to the lightkeeper's cottage.

That's where he woke up, about an hour later, brought around by the strong scent of the "restoratives" they'd been using on him — probably vinegar or smelling salts. And that's where they were forced to give him the terrible news.

His son, Joseph, was dead. By the time the rescuers had reached the ship, the boy had already succumbed to exposure; his father was cradling his corpse in his arms when they found him. They'd brought the body down from the rigging — grisly, awkward work made worse by the relentless waves; one of the dredge crew had been knocked off his feet, tumbling into the hold with the cadavre. Once they'd managed to get it off the ship, Thomas Tinning had rowed the body off to the morgue in his lifeboat. Another name added to the list of those killed in Toronto's waters.

It's hard to know just how many ships have been wrecked on the beaches of our islands. When the City began planning an erosion control project back in 2017, their background research found evidence of more than half a dozen shipwrecks in the area around Gibraltar Point alone. The Toronto. The Sir John Colborne. The Young Leopard. The Eliza Wilson. The Admiral. The Jane Ann Marsh. When a government yacht called the Toronto sank at Gibraltar in 1811, the wreckage was used to build a new twelve-gun frigate to fight the Americans in the War of 1812. When the Monarch ran aground in 1856, it lured another to ship to its doom; sailors mistook a light on the wreck for the beacon of the lighthouse. And when waves began crashing over the sides of the W.A. Glover in 1867, the wheat it was carrying got wet, swelled, and burst through the sides of the schooner.

What was left of the Anna Bellchambers didn’t last long after that stormy October morning. The ship was broken up by the wind and the waves, and the wreck was consumed by the hungry sands of Gibraltar Point. It's not alone down there. The islands have swallowed up countless vessels; a hidden nautical graveyard lies beneath our shifting shorelines. And every few years or so, the wreckage of at least one old vessel emerges from those sands. It's thought to be the wreck of the Monarch, but it's a reminder of all the ships that have been lost in our seas, and to the lives ended on board them.

Then, the sands shift once more… and the shipwreck disappears.

A Frustrating History of Getting Around Toronto — My New Online Course!

I thought I’d share the story of a shipwreck this week because I’ve just opened the registration for my new online course — and shipwrecks are going to be part of it!

People in Toronto are no strangers to the challenges of getting around. Those frustrations have a long history in our city, stretching all the way back to its founding and beyond. In this four-week online course, we’ll dive into some of the most fascinating Toronto transportation tales — from shipwrecks and stagecoaches to traffic jams and train derailments. We’ll learn about the warships that once sailed the waters of Lake Ontario, the exciting summer when bicycles first arrived in our city, the portage trail that gave Toronto its name… and much, much more.

The course will kick off on May 17 and be held every Wednesday night at 8pm. If you have to miss any classes, don’t worry! All the lectures will be recorded so you can watch and re-watch them whenever you like. And if you’re a paid subscriber to The Toronto History Weekly, you’ll get 10% off!

A Weird & Grisly Thank You For Paid Subscribers! An Exclusive Online Soiree!

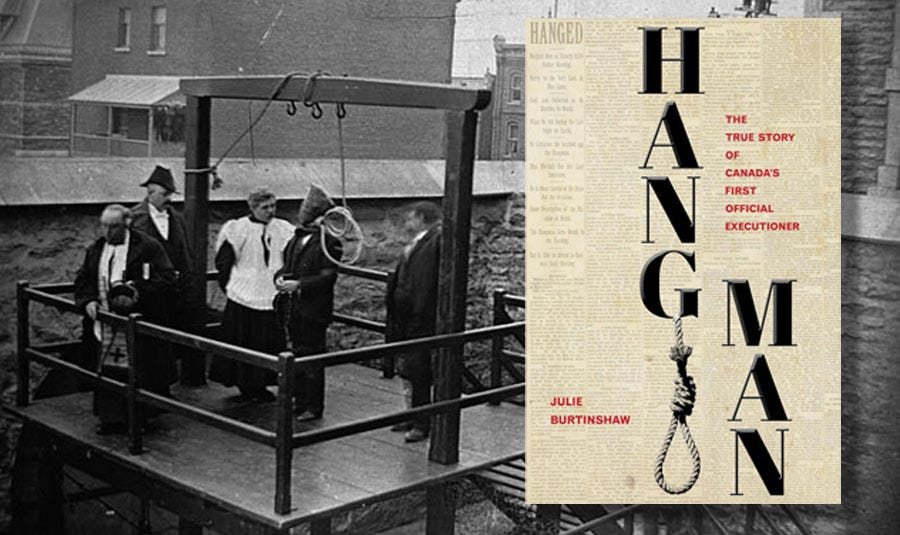

John Radclive has a gruesome place in Canadian history. In the late 1800s, he was hired to become our country’s first official executioner. He would spend decades in the role, killing scores of people. The photo above is from one of his hangings; thought to be the last public execution held in Canada. And now author Julie Burtinshaw has published a new book all about Radclive and his life: Hangman: The True Story of Canada’s First Official Executioner. Having shared a few grisly historical tales myself, I’ve been very excited to read it. And now I’m even more excited to get the chance to have a chat with the author over Zoom — and all of you paid subscribers are invited to join us!

I’ve been looking for some unique ways to thank those of who’ve been willing to support The Toronto History Weekly with a few dollars a month. It’s only thanks to you that the newsletter gets to continue! So if it goes well and we get a nice crowd, I’m hoping to organize more of this kind of event in the future.

The gruesome soiree will be held over Zoom at 8pm on the night of Monday, May 8. I’ll send out the link to all paid subscribers ahead of time.

Hope you can join us!

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber and you’d like to make the switch, all you have to do is click the button below. Not only will you get invited to exclusive events like the one above, you’ll also be supporting all my work while helping to ensure The Toronto History Weekly survives. This newsletter is a ton of work! Only about 5% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 20 other people.

The King of the Bootleggers — Now With A Nifty Map!

Last summer, I shared the dramatic tale of Rocco Perri and his mysterious disappearance. He was known as “The King of the Bootleggers” and ran much of Toronto’s boozy underground during the days of prohibition. Now, that article has been re-published by Torontoverse — along with a neat, interactive map of Perri-related locations around the city.

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

HUNGER STRIKE NEWS — The Niagara graveyard hunger strike has ended. I wrote about James Russell last week. The 76-year-old Toronto man had chained himself to a plaque demanding that the local government in Niagara-On-The-Lake restore and preserve the graves of early Black settlers. He has now ended his hunger strike, but plans another protest as the authorities promise to work toward the restoration. Read more.

SAVING THE SCIENCE CENTRE NEWS — You’ve probably heard about Doug Ford’s plan to move the Ontario Science Centre to Ontario Place, apparently as an attempt to help sell his plan to hand a huge amount public park space over to a private spa. A petition is making the rounds, calling on the premier to abandon the plan. It has more than 20,000 signatures so far. Sign it.

BASEBALL, CRICKET AND SHOOTING BIRDS NEWS — Bob Georgiou has compiled “A Quick History of Sporting East of The Don River,” which includes the unexpected story of the old shooting rounds. Read more.

THERE’S BEEN MORE THAN ONE GOLD HEIST NEWS — Millions of dollars worth of gold were stolen at the airport this week. And unbelievably, as Alex Arsenych explains, “Pearson has been the scene for a Hollywood movie-esque gold heist before – roughly 70 years ago – and it still remains a mystery to this day.” Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

TEN OF TORONTO: WHAT DO TEN NEIGHBOURHOODS TELL US ABOUT WHO WE ARE?

Until April 30 — Myseum — 401 Richmond Street West

“Toronto is vast and diverse in people, places, and experiences. With 2.8 million of us who call this dynamic city home, we explore what it means to call Toronto a ‘city of neighbourhoods’ through the lens of 10 distinct communities and themes. In Ten of Toronto, we reflect on our shared histories by looking at the forces that have shaped the city’s neighbourhoods: geography, economy, immigration, finance, urban development, culture, inequality, and social values. Join us, steal away, and stay awhile. We invite you to discover your own path through the stories and histories we’ve unearthed for this exhibit, and lend your voice – what do neighborhoods mean to you?”

Free!

I TURN MY CAMERA ON: TORONTO ALT-ROCK IN THE 1980s

Until April 30 — The Local — 396 Roncesvalles

West end bar The Local will be displaying photographs taken by Jeremy Gilbert during the golden age of Toronto alt rock.

Free presumably!

BLACK HISTORY IN ONTARIO, 1793–1965

April 27 — 7:30pm — Online — The Toronto Branch of the Ontario Genealogical Society

“Winston Anderson will be presenting a timeline of events from the passing of the Act To Limit Slavery in 1793 by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe, to 1965 when MPP Leonard Braithwaite pushed for the Separate Schools clause on segregated schools for Blacks to be officially removed from the provincial education policy. He will be discussing a number of people of Black heritage, both free and enslaved people, who shaped Toronto.”

Free!

THE DON: INMATES, GUARDS, GOVERNORS AND THE GALLOWS

April 26 — 7pm — Northern District Library (Room 224)

“Join writer and researcher Lorna Poplak as she presents facts behind the Don Jail's location and construction and shares tales about inmates, guards, governors, gangs, officials and even a pair of star-crossed lovers whose doomed romance unfolded in the shadow of the gallows. The illustrated talk will highlight the Don's tumultuous descent from palace to hellhole, its shuttering and lapse into decay, and its astonishing modern-day metamorphosis.”

Free!

ERNEST HEMINGWAY IN TORONTO

April 27 — 2pm — Brentwood Library

“Ernest Hemingway lived in Toronto during 1923 while he worked for the Toronto Star newspaper. He had moved to the city from France with his pregnant wife Hadley, as she preferred to give birth in North America. Their son, John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway, was born at Wellesley Hospital, in Toronto, on October 10, 1923. This special centennial presentation considers the role the area played in Hemingway's apprenticeship as a writer, and in his personal life.”

Free!

USING TORONTO’S ASSESSMENT RECORDS IN YOUR RESEARCH

May 4 — West Toronto Junction Historical Society

This is part two of a series about researching the history of your house, presented by Jane MacNamara of the Ontario Genealogical Society.