The Story Behind Toronto's Green Park Benches

Plus a boozy history of Toronto, an architectural mystery, and more.

This week, I’m going to share the unexpected story behind some of Toronto’s most iconic park benches, solve an architectural mystery, and more. But I want to start by sharing some exciting news: I’m offering a new online course!

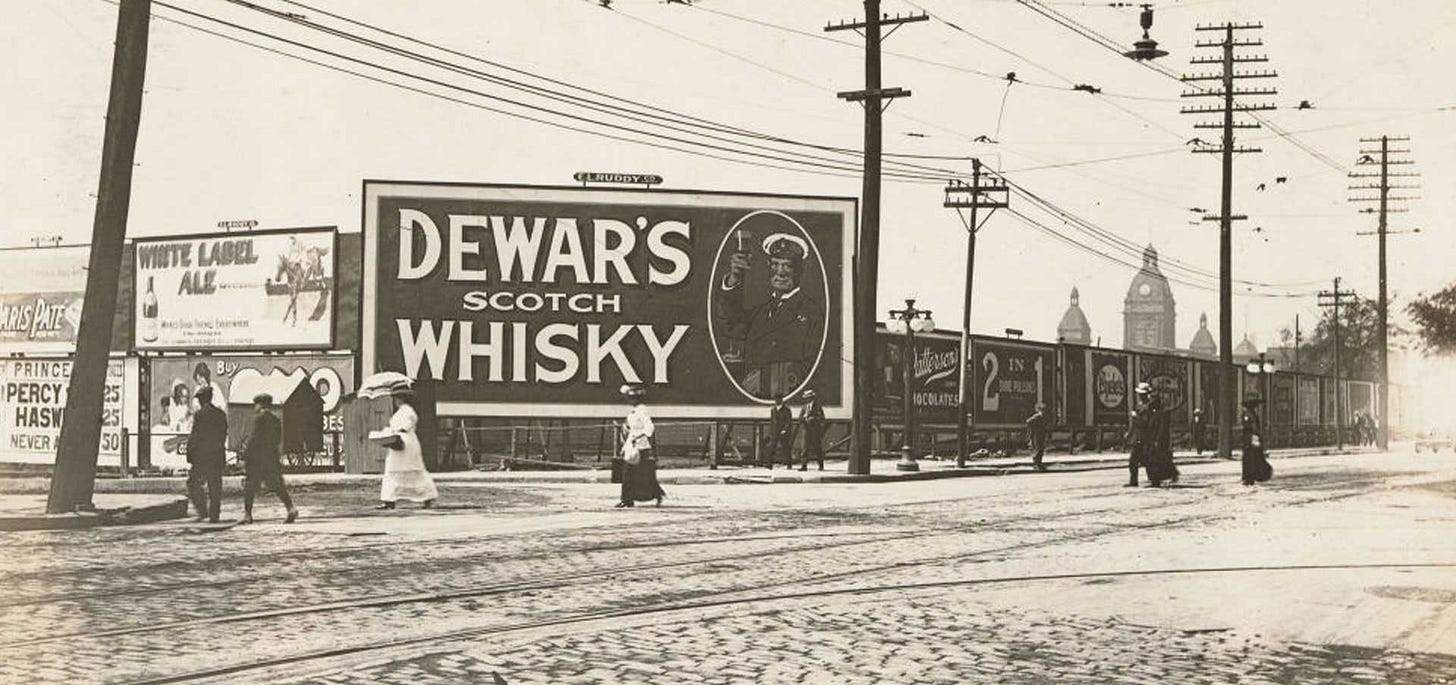

I’m calling it A Boozy History of Toronto.

Alcohol has always been a dramatic part of life in Toronto — from the days of colonial treachery to modern debates over drinking in parks. In this four-week online course, we'll meet drunken rebels, beer-bashing mayors, notorious bootleggers, and alcoholic politicians. We'll witness booze-soaked murders, prohibition-era shootouts, and the kidnapping of one Canada's wealthiest brewers — plus, the bitter fight over whether drinking should be allowed at all. To truly understand Toronto, it helps to understand how this city has been shaped by centuries of people getting drunk.

The course will kick off on July 14 and run on Thursday nights for four weeks — but if you’re not free on any of those days, don’t worry. I also record all my lecture and post them to a private YouTube page so you can watch them anytime you like. Plus, if you’re a paid subscriber to this newsletter, you’ll get 10% off!

If you’d like to switch to a paid subscription to The Toronto History Weekly so you can score that 10% discount, you can do that by clicking on this big blue button:

And it will also allow you to subscribe for free if you haven’t done that already.

THE STORY BEHIND OUR GREEN PARK BENCHES

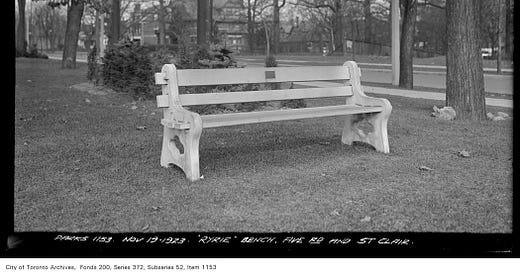

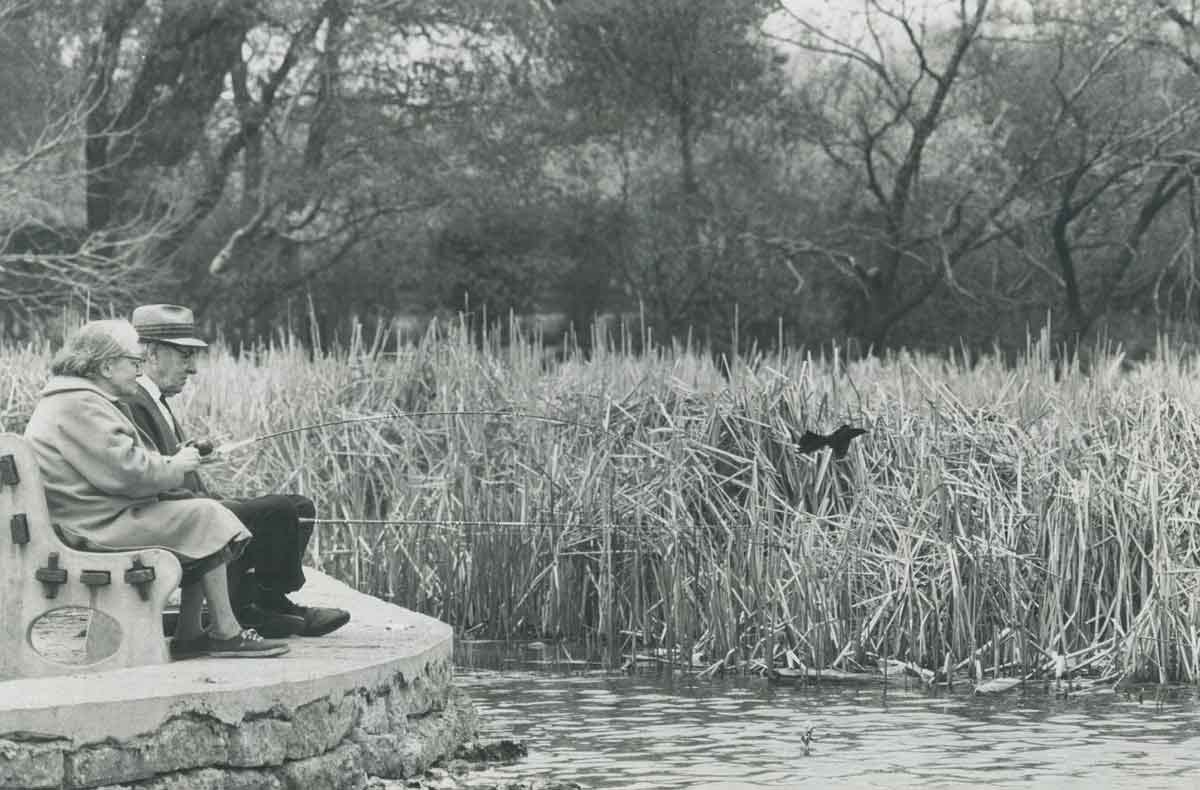

REST YOUR BONES NEWS — If you’ve spent much time in Toronto parks, you’ve likely come across one at some point: a bench made of green wood suspended between two concrete frames. They’re such a ubiquitous and mundane part of life in our city that it’s never occurred me there might be an interesting story behind them. But it turns out there is.

Stephen Wickensshared an old newspaper article on Twitter last week (originally posted in Joanne Doucette’s “Toronto’s Beaches Historical Photos” Facebook group) which traces the benches back to a man named Harry Ryrie:

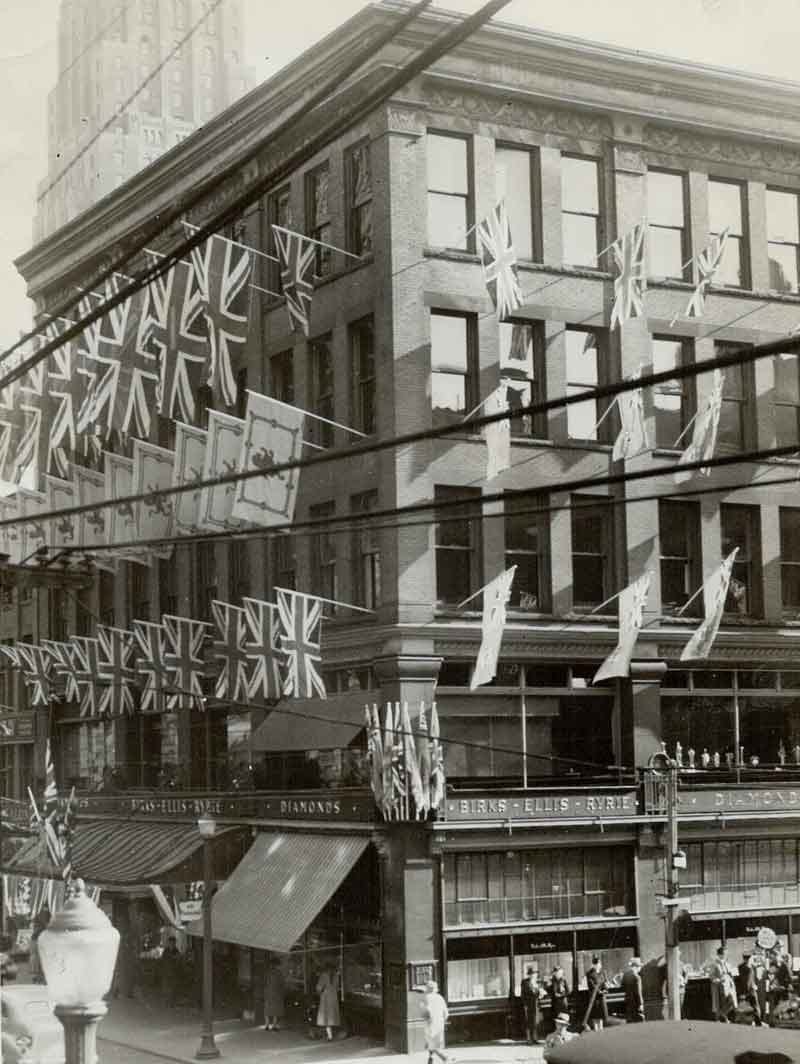

The Ryries were among Toronto’s great Victorian jewellers. It began with James Ryrie, who worked as an apprentice at a pretty little shop on Yonge Street before taking it over himself in the 1870s. That seems to have been when his partnership with his brother Harry began. And it was a very successful one.

The jewellery industry in Toronto was booming in the late 1800s. And after a few rough years filled with late nights and financial losses, the Ryrie brothers began turning a big profit. They were able to expand, first taking over the neighbouring storefront and then moving up the street to a big new home on the corner of Yonge & Adelaide.

Stained-glass windows. Domed ceilings. Chandeliers. Luxurious goods laid out in cherry wood display cases. Their new shop was hailed as one of the most attractive on the continent. And it kept expanding from there. Ryrie Brothers soon swallowed up more storefronts and launched a mail order catalogue to reach customers far beyond Toronto’s borders.

And even that was just the beginning. The Ryries would eventually strike a deal with another one of Canada’s big jeweller families. The Birks had been having similar success in Montreal — a name that’s still in the business to this day. Together, they’d open a huge new store on the corner of Yonge & Temperance.

It was known as “Diamond Hall.” It was five storeys high, with marble columns and a facade of bronze and mahogany. And since it was now 1905, they filled the building with modern conveniences. Electric lights. A telephone switchboard. Pneumatic tubes. Cash-counting machines. Even an automatic fire alarm system. Diamond Hall would be a Yonge Street landmark for decades to come.

Harry Ryrie used his fortune to become something of a public figure in Toronto. He was the president of the local YMCA, active at Jarvis Street Baptist Church (which still stands next to Allan Gardens), and the founder of an organization that cared for soldiers during the First World War. He also invested in real estate: he built the Ryrie Building at Yonge & Shuter; it’s still there today, home to Urban Outfitters.

But there was another legacy yet to come.

Harry Ryrie wouldn’t live to see the end the war. He died in 1917. And when he did, he left part of his fortune to the city to be used for the purchase of park benches. Six hundred of the “Ryrie Benches” would be placed in parks across Toronto. As the newspaper article Joanne Doucette and Stephen Wickens shared on social media explains, “The intention is to have these distributed throughout the Island, Sunnyside, and other city parks, so that the public may expect the privilege of enjoying this thoughtful and much-needed gift from one of our late citizens.”

AN ARCHITECTURAL MYSTERY ON YONGE STREET

I WAS VERY CONFUSED NEWS — As I wrote the story above, I fell down another rabbit hole. I was mystified by one small detail in the history of Ryrie Brothers. It involved Diamond Hall, their big building at the corner of Yonge & Temperance, and one simple question: Was it still standing there today?

Usually, that’s a pretty easy thing to answer. Just check streetview on Google Maps, or head down there in person, and see whether the building is still there or not.

Sometimes, getting that answer can be a little bit tougher. If the building has been renovated, you might need to look for hints in the archival photos, checking to see whether the number of storeys or the windows match the building that stands there today, or whether there are other architectural details to tip you off.

This time, none of that worked.

There is an old building standing on the south-west corner of Yonge & Temperance today. It’s now home to Sud Forno, an Italian restaurant. Their website describes it as a “heritage building” and it certainly looks old enough to be Diamond Hall. A little more digging suggests it was built in 1894. I was under the impression the Ryrie brothers built Diamond Hall for themselves in 1905 — that it was a brand new building when they moved in — but maybe I was wrong? Maybe it had been around for a decade before that? It could make sense.

But nothing else made any sense at all.

For one thing, the archival photo of Diamond Hall didn’t match the heritage building I found standing on that corner in Google Maps. It has the wrong number of windows in the wrong places. The columns don’t look the same. None of the mouldings and other details are anything alike.

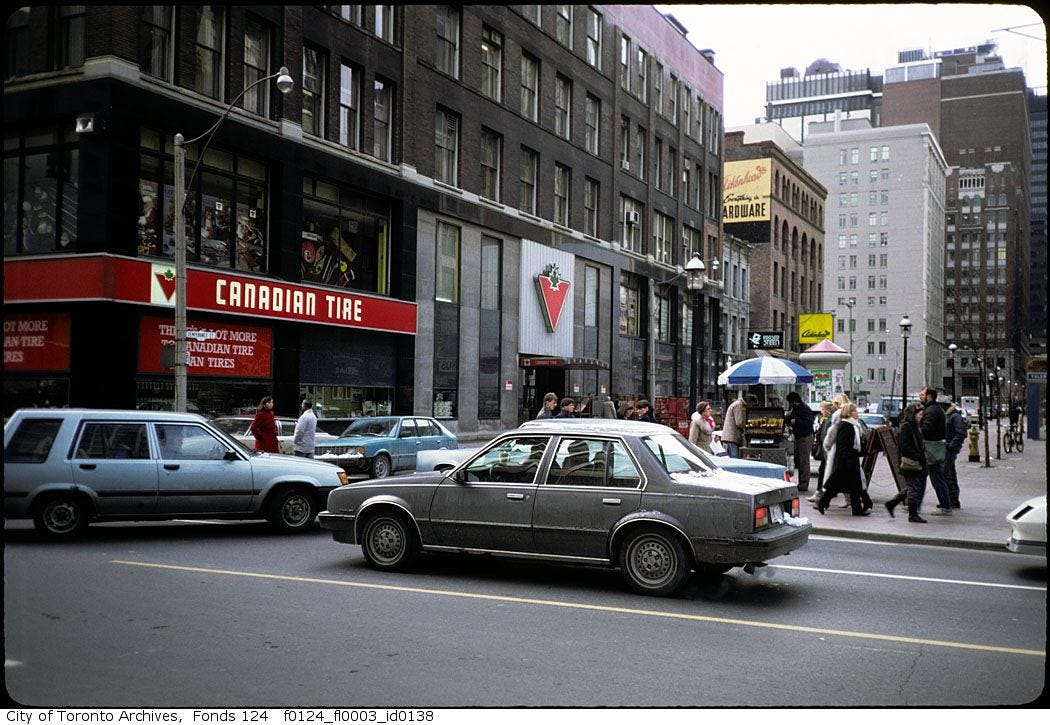

But how is that possible? Diamond Hall definitely stood on that corner from at least 1905 until the late 1980s, when it was home to a Canadian Tire — as you can see in this photograph from the City of Toronto Archives:

Given the laws of physics, how can another heritage building be standing on that same corner?

Well, I finally found my answer in a Globe and Mail article written by Dave LeBlanc just a few years ago. It is, as he puts it, “A tale of moving heaven and earth — well, actually, brick, mortar, silicone moulds and some glass fibre-reinforced concrete.”

It seems that Diamond Hall was demolished not long after that photo of the Canadian Tire was snapped. A massive new development was slated to take over much of the block.

The Bay-Adelaide Centre was designed to be one of the biggest towers in Toronto: a 57-storey behemoth that would cost nearly a billion dollars to build. A new building on the spot where Diamond Hall had previously stood became part of that development; LeBlanc says it was “an ugly, non-heritage, four-storey building that housed the massive mechanical systems for the entire complex, as well as a ground-floor retailer.”

Then, before the new tower could rise into the sky, a recession hit. The whole project stalled. The Bay-Adelaide Centre was put on hold. The only bits that did get built were the underground garage, a six-storey bunker-like stump of an elevator shaft, and the Cloud Gardens Conservatory that had been given to the city in exchange for allowing the developers to build such a tall tower in the first place.

It wasn’t until the 2000s that construction started up again; this time with a new plan for three big towers. The project would mean demolishing some more old buildings, but not all of them. While much of the block would be turned over to modern glass and steel, the corner of Yonge & Temperance would become a “heritage gateway.”

It would evolve in three parts:

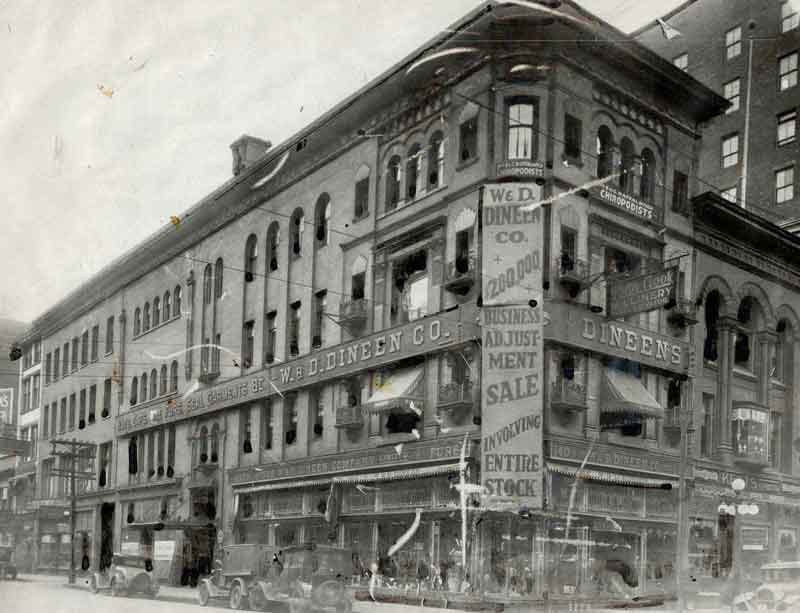

1. THE DINEEN BUILDING

Just across the street, on the north side of the corner, the Dineen Building was already being restored. Built in 1897, the beautifully curved yellow-brick structure was originally home to the Dineen Hat and Fur Company. It now houses the Dineen Coffee Co. and a couple of restaurants.

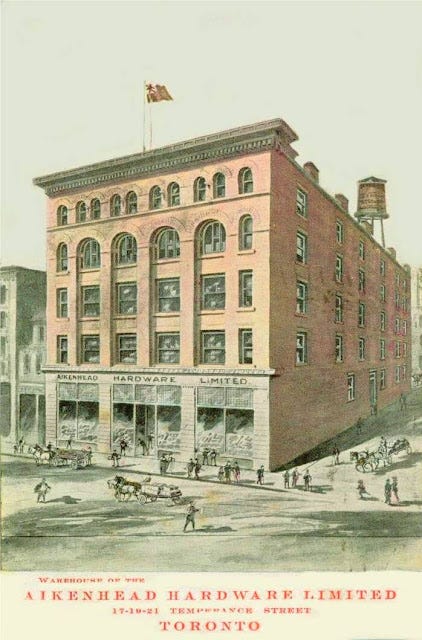

2. THE AIKENHEAD’S HARDWARE BUILDING

Meanwhile, another heritage property stood on the south side of Temperance. The Aikenhead’s Hardware building had also been built in the 1890s. It was designed by Toronto’s most famous Victorian architect, E.J. Lennox (the guy who did Old City Hall and Casa Loma), for one of the city’s oldest businesses (Aikenhead’s Hardware had originally been founded by the Ridout family all the way back in the 1830s and would eventually get swallowed up by Home Depot).

Right around the same time Diamond Hall was demolished, that old hardware building seemed to be in real danger. It was standing right in the way of the original plans for the Bay-Adelaide Centre, and Toronto had earned a reputation for thoughtlessly destroying much of its built heritage.

But that was beginning to change — at least, a little bit. Some of those big new downtown bank towers had begun incorporating facades rather than simply destroying them. And when the original plans for the Bay-Adelaide Centre were drawn up, the Aikenhead’s Hardware building was saved instead of being destroyed. The developers picked it up and moved about 40 meters down the street — to its current home: the lot next to the old Diamond Hall location — just before the recession hit and construction stopped.

3. THE ELGIN BLOCK

So, when the Bay-Adelaide Centre project was started back up in the 21st century, the developers saw an opportunity. Diamond Hall was gone, but if they found a way to put another beautiful old building on that corner — in the same place where the Ryrie brothers had once sold their jewels — it would create an elegant “heritage gateway” onto Temperance Street.

So, that’s what they did.

The Elgin Block had been standing just to the south on Yonge Street since the 1850s. And it had a rich history of its own. It was once home to William Lyon Mackenzie’s office — the old rebel mayor published a newspaper there in his later years — and Ryrie Brothers had called it home for a while, too. It was going to be replaced by the new towers, but the architects saved part of it.

They grabbed a pair of the Elgin Block’s facades — the ones on the corner of Yonge & Adelaide — and moved them a block north to become the new corner of Yonge & Temperance, taking over the place where Diamond Hall had once stood.

They even gave the “new” building a bit more length, using a silicone mould to copy over part the facade and create a “ghost building.” You can see it clearly today: a pale continuation of the Elgin Block’s facade (on the left in the photo above).

So that’s the very complicated and convoluted answer to the mystery that had me so stumped. How can one heritage building be standing on the very same corner as another heritage building?

If you move it there, of course!

I should also quickly mention that the story behind the name of Temperance Street is fascinating in its own right, deeply connected to one of the central conflicts in our city’s history: the battle over whether people should be allowed to drink. I’ll be talking about it in “A Boozy History of Toronto” — the new online course I mentioned above. You can learn more about it here.

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

WHY OUR CITY MAKES IT SO HARD TO PEE NEWS — I’ve rambled on about benches and facades for so long that I’ve run out of room in this week’s newsletter (I’m getting the warning alert from Substack telling me I’m up against the length limit), but there is one quick link I wanted to make sure I include:

John Lorinc published a three-part series at Spacing this week. “Why We Can’t Go: A Report on Toronto’s Public Washrooms” begins by exploring the history and origins of our city’s lacklustre approach to relief, much of which is tied up not only with penny-pinching, but with moral panic and homophobic. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

JUDGE GRIZZLE: CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST

JUNE 27 — 7:30pm — Online — Toronto Branch, Ontario Genealogical Society

“Stanley George Sinclair Grizzle was a Canadian citizenship judge, a soldier, a political candidate and an activist. Born in Toronto to Jamaican immigrant parents at the end of WWI Stanley G. Grizzle became a railway porter at 22, founded the Railway Porter’s Trade Union Council and was active in the labour movement throughout his life, becoming the first African-Canadian member of a trade union. Mr. Grizzle was an associate editor and columnist for Contrast, a black community newspaper and penned the book My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada. In 1959 Mr. Grizzle and Jack White became the first African-Canadians to run in an Ontario election. Mr. Grizzle has also received the Order of Ontario, Order of Canada and the Order of Distinction from Jamaica for his valuable contributions to Canadian society.”

Free with registration!

SUMMER HISTORY SERIES: THE KINGSWAY

July 21 — 7:30pm — Online — Etobicoke Historical Society

“One of Canada’s premier neighbourhoods, The Kingsway was the vision of one man, Robert Home Smith. A lawyer by training but a natural-born town planner, Home Smith took 3,100 acres of ordinary Etobicoke farmland and turned it into an elegant series of subdivisions that were deemed ‘A bit of England far from England’. Centered around the Old Mill, they offered not only a new vision of town planning but of upper middle class life in Toronto. So ‘jump on the bus’ with EHS Historian Richard Jordan for an enjoyable virtual journey through this picturesque and historic neighbourhood.”

Free for members; an annual membership is $25.

MY UPCOMING EVENTS

THE TORONTO CIRCUS RIOT: A TRUE TALE OF SEX, VIOLENCE, CORRUPTION AND CLOWNS

August 3 — 7:30pm — Online — Toronto Branch, Ontario Genealogical Society

The strangest riot in our city’s history broke out in the summer of 1855. It was sparked by a brawl at a King Street brothel, when some rowdy clowns picked a fight with a battle-hardened crew of firefighters on the most dangerous night of the year. That bizarre encounter would reverberate through the city. The circus performers had made a terrible mistake; those firefighters were members of the Orange Order, the powerful Protestant society that ruled Toronto for more than a century. And they wanted revenge. The circus grounds would soon become the scene of a bloody clash that shook Toronto to its core and laid bare the fault lines that once violently divided our city.

Free with registration!