The Notorious Lizzie Lessard

Plus my new online course starts this week, shoes, money, hair cuts, and more...

On a September morning in the year 1900, a police wagon approached Old City Hall. Back then, the building was still Toronto's new City Hall, having opened only a year earlier. The impressive stone edifice wasn't just home to our municipal government, there were courtrooms inside, too. Every weekday morning, a wagonful of accused prisoners was driven over from jail to face trial. It usually went off without a hitch. But on this particular morning, one of those prisoners had another idea.

The wagon pulled into the courtyard at the heart of Old City Hall, passing through the elegant back entrance, the click of the horses' hooves echoing off the thick stone walls. Once it came to a stop, the prisoners were unloaded and marched into the building, guarded by a quartet of police officers. That's when she saw her opportunity.

Her name was Lizzie Lessard. She was no stranger to this process. She was only in her early twenties, but she was already a veteran of the justice system. A petty criminal, she'd been in trouble with the law since the age of sixteen. She was arrested many times over the yeasr; this time, on the vague charge of "vagrancy." But she wasn't planning to stick around for her trial.

As she walked into City Hall with the other prisoners, Lessard was bringing up the rear. And she noticed there was no police officer walking behind her — no one standing between her and her freedom. She moved quick. She spun around and made a dash for the door, then slipped across the courtyard, in through another entrance, rushed across the hallway, and out onto the street. No one stopped her. Lizzie Lessard had escaped.

Now, she was on the lam. It wasn't long before the police noticed she was gone, but by then it was already too late. She'd darted across James Street and into the Eaton's department store (which stood on the same spot the Eaton Centre stands today). Then, she disappeared. The police couldn’t find her.

She doesn't seem to have gone very far, though. We don't know much about what she got up to that afternoon, but she may have spent the entire day laying low inside Eaton's. At some point, she paid a visit to the millinery department, where she admired a fine black velvet hat. In fact, she liked it so much she slipped it onto her head, leaving her own black straw hat in its place. She would later claim she bought it, thinking it would make an effective disguise and fool the police. But as she walked out of the store onto Yonge Street — six hours after making her escape — she was immediately recognized by a constable who arrested her on the spot.

A few days later, she was back at City Hall. And this time when she tried to escape, she didn't make it out of the building. She was caught and forced to stand trial for stealing the velvet hat.

Her fate rested in the hands of a man named George Denison III. The police magistrate. His family was one of the most prominent in our city's history. His great-grandparents had been among the first settlers to arrive in the late 1700s, when the British first began building their new capital on this Indigenous land. The Denisons became leading members of the Family Compact — the small group of conservative elites who ran the colony. They also enslaved a woman named Amy Pompadour — "given" to them as a "gift" by a member of the Russell family. Three generations later, George Denison III would follow in those racist footsteps.

During the American Civil War, he acted as a secret Confederate agent, supporting spies from the South who used our city as a base of operations, launching raids across the border into the northern states. Elected to municipal office, Denison was the only member of city council to vote against a motion expressing sympathy after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. And when the Confederate president Jefferson Davis moved to Canada after the war, Denison organized a cheering crowd to welcome him.

It was a decade later that Denison was talked into accepting the job of police magistrate, with the powers of a judge. He would hold the post for the next half century, all the way into the 1920s, with influence few judges in our city ever have wielded. Denison heard 90% of all the indictable cases in Toronto, thousands of them a year. He was famous for the speed with which he raced through his work, sometimes handing down dozens of judgements in a single hour. His courtroom was such a spectacle it became a noted attraction for tourists.

Lizzie Lessard was one of its most notorious stars. She appeared before Denison many times over the years — first at the old courthouse on Adelaide Street (now a Terroni restaurant; you'll still pass the old jail cells on your way to the bathroom), then at Old City Hall. She didn't find much leniency there. Denison liked to trust his gut. “This is a court of justice," he once explained, "not a court of law.” And his gut tended to favour a particular kind of defendant: the more someone fit his vision of a respectable, white, British, Protestant Toronto, the better they tended to fare. And once Denison handed down a decision, it was almost never overturned on appeal. These were the days of "Toronto The Good," when city leaders were determined to impose Victorian ideals of vice and virtue, and the new Toronto Police Morality Squad cracked down on anything they felt to be sinful.

In court, Lessard faced one sentence after another. For vagrancy. For drunkenness. For stealing an ostrich feather from Eaton's and a fur muff from the Simpson's department store. Once, it was even for "fouling the post" with a lewd letter. The Toronto Evening Star called it "obscene… one of the filthiest possible." Some historians think it may have been a love letter to another woman, though some press reports make it seem more likely to have been filled with graphic threats.

Lessard's appearances in court were often memorable — highlighted by small but dramatic acts of resistance — and the newspapers found them endlessly entertaining. It wasn't just escape attempts. The Star reported that when she was convicted of drunkenness, "She treated the Magistrate to an exhibition of profanity." When she was convicted of shoplifting, she even managed to land one the most notable courtroom kisses in the city's history. As I wrote in The Toronto Book of Love, "As she was led out of the courtroom for yet another stint behind bars… she delivered a resounding smooch on the lips to one of her fellow prisoners: a kiss so prodigious it left the Toronto Daily Star amazed.

“'There are kisses at weddings, there are kisses of farewell as the train is pulling out — but louder and more fervent than all of these was the smack to-day in court,' the newspaper told its readers. 'Some kisses are sweet as cider fresh from the bunghole, some kisses are like the report of an elephant pulling a foot out of the mud. Of the second variety was the kiss to-day in court. Smack!' The staff inspector was startled by the sound; he looked around as if a gun had just been fired. 'But there was no gun — Lizzie Lessard had simply kissed her prison companion, John Kelly, as she bade him farewell in the dock.'"

But behind the amusing headlines, there were hints that Lizzie Lessard's story wasn't a comedy but a tragedy. Despite the petty nature of her crimes, most of her convictions ended with months spent behind bars. And as a prolific repeat offender, she was soon spending more time in prison than out of it. A couple of years after her daring escape, she was back in court at Old City Hall sporting a black eye. The police claimed they didn't know where she'd gotten it; Denison ignored Lessard's pleas to investigate. Instead, he handed down yet another sentence: a $25 fine or an additional six months behind bars. Lessard begged for leniency; she'd just been released after serving time for another crime and needed time to raise the money to pay the fine. Denison refused. "Lizzie's audible grief," the Star reported, "resounded in the vaults below."

And so, Lessard was sent right back into the belly of one of the most hellish places Toronto has ever known.

The Andrew Mercer Reformatory for Women was the first women's prison to open anywhere in Canada. It stood in what's now Liberty Village — on the spot where Alan Lamport Stadium stands now — holding prisoners convicted of a wide variety of offences, everything from murder to drunkenness to the common catch-all charge of "vagrancy," which allowed the police to arrest just about anyone. It was in operation for nearly a century — from the 1870s to the 1960s — until finally being shut down in response to stories of the horrors that took place within its walls.

The women of the Mercer suffered terribly. It was a brutal place, where inmates were subjected to abuse, torture, even medical experiments. Lessard had first been sent there as a teenager in the late 1800s; over the next two decades, she was sent back over and over again. And with every visit to the Mercer, she began to resist her incarceration more and more.

"Lessard did everything in her power to subvert the dehumanization of institutional life," as historian Carolyn Strange explains, "where petty infractions such as chewing gum or speaking sullenly could put a woman on a discipline report." Lessard was punished for swearing, for breaking dishes, for destroying what little furniture she had in her tiny cell — sometimes she was reported for two infractions in a single day.

But nothing compared to her dramatic final visit.

In 1909, Lizzie Lessard was back at the Mercer once again. She was still only in her early thirties, but had already been imprisoned eighteen times. Her hard life was beginning to take a terrible toll. She was ill and her patience seems to have been wearing thin; she was lashing out more often. In her final month at the Mercer, she was punished over and over again. Sent to the "dungeon." Given only bread and water. Not allowed to leave her cell for days on end.

The final straw came when one of the Mercer's most hated wardens, Maggie Mick, punished her for making threats and using foul language, giving her two weeks of solitary confinement in the basement. That's when Lizzie Lessard decided to take her revenge.

The Mercer was founded on the idea that labour would help reform "fallen" women. Prisoners were expected to spend their days silently working at sewing machines. It can't have been hard for Lessard to get her hands on a pair of scissors. Just a few years earlier, another inmate had stabbed Mick and vowed to end her life. Lessard must have heard about that attack and taken it as inspiration, but she added her own twist.

By then, Lessard was suffering from a fatal case of syphilis. It had already begun to slowly kill her, and she planned to take Mick with her to the grave. She's said to have tainted the scissors with her disease in preparation for her own attack. When she got her chance, she plunged them into the warden's breast, aiming not just to wound her but to infect her with the syphilis. And with that final brutal act, her time to the Mercer came to an end. The assault led her to be convicted of a more serious charge and sent to the Kingston Penitentiary. That's where she passed away just two years later.

It was a tragic end to a difficult life. But while most people in her position left little evidence of their lives, Lizzie Lessard was different. She'd resisted every step of the way. Whether it was by escaping from custody, or by planting a memorable kiss on the lips of a fellow convict, or by stabbing a warden with a syphilitic pair of scissors, she'd left a blazing trail through the historical record. And so, while so many of Toronto's petty criminals have disappeared with little trace, the notorious Lizzie Lessard most definitely left her mark.

Velma Demerson was one of the women incarcerated at the Mercer Reformatory. She was sent there after falling in love with a Chinese-Canadian man and becoming pregnant with his baby at a time when that’s all you needed to get sent away. Her time there included being subjected to horrifying medical experiments; she spent the rest of her life fighting for compensation and sharing her story — including in her autobiography, Incorrigible.

I also wrote about her in The Toronto Book of Love, and Lizzie Lessard comes up a couple of times in there, too.

If you’d like to know more about the secret Confederate agents who were operating in the Canadian colonies during the American Civil War, they’ll be one of the things we talk about in our next big two-part episode of Canadiana, which you can subscribe to for free on YouTube.

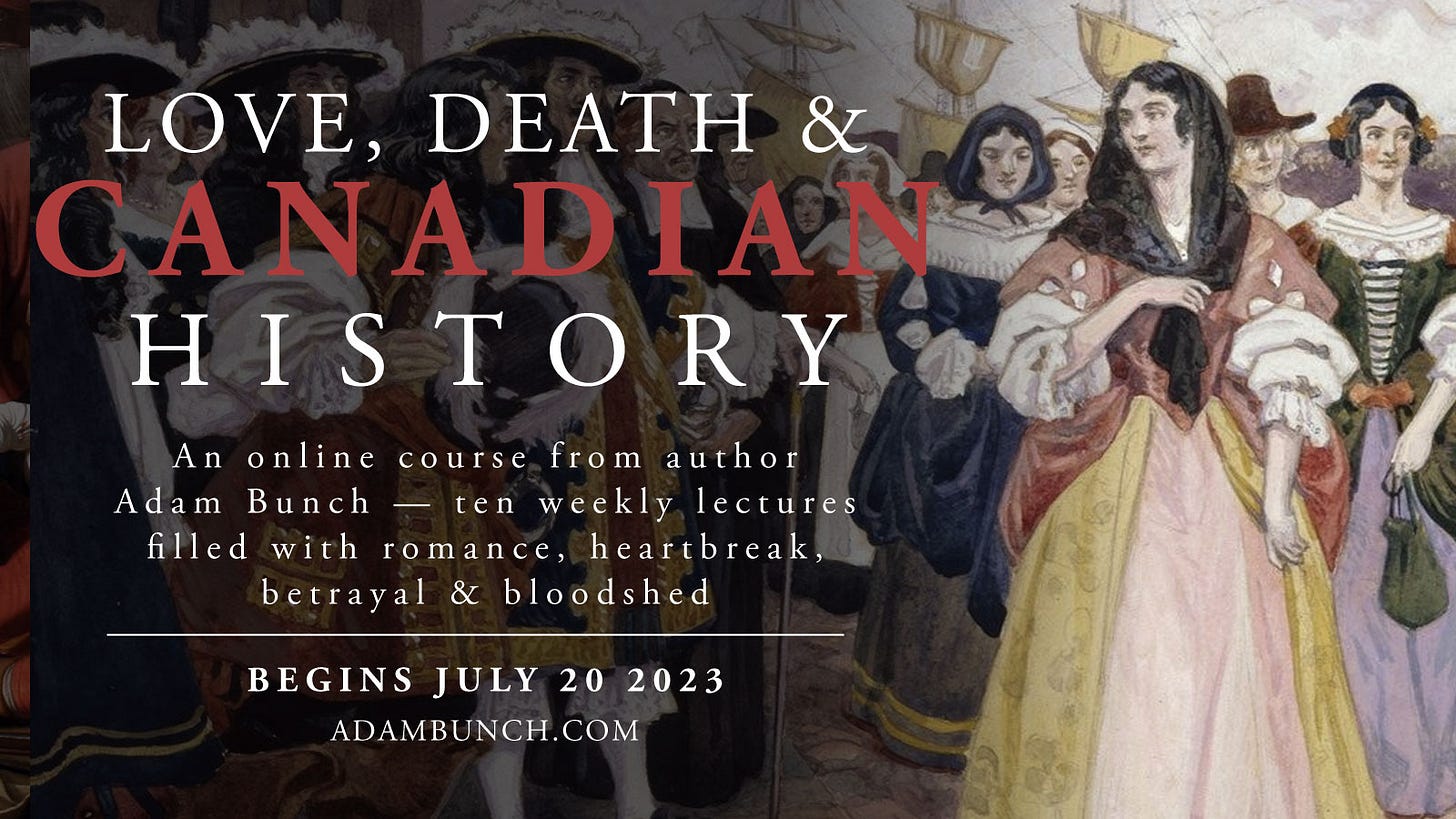

My New Online Course Starts This Week!

Canadian history is much more than dry lists of dates and events. It's filled with gripping tales from the lives of historical figures who were people much like us — who fell in love, suffered broken hearts, were fascinated by death and devastated by loss. Those stories of love and death have a lot to teach us about our country. In this ten-week online course, we'll explore the history of this place from time immemorial to the recent past, uncovering torrid affairs and shocking scandals, duels, murders and executions. And we'll discover the ways in which those passionate and morbid tales have shaped the country we live in.

The course will kick off on the night of Thursday, July 20. And if you’re interested but concerned you might have to miss some classes, don’t worry — all the lectures will be recorded and posted to a private YouTube playlist so you can watch them whenever you like. Oh, and paid subscribers to the newsletter get 10% off!

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber to the newsletter and you’d like to make the switch, all you have to do is click the button below. This newsletter is a ton of work! Only about 4% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 25 other people — in addition to getting perks like 10% off my online courses:

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

WHERE DAVID BOWIE GOT HIS HAIR CUT NEWS — Toronto’s planning and housing committee is recommending that City Council give heritage protection to five buildings at the corner of Yonge & Isabella, including the old premises of the House of Lords hair salon (where everyone from David Bowie to The Rolling Stones to Alice Cooper is said to have gotten a trim). It sounds like it’s an attempt to get the facades incorporated into the new tower planned for the site. Read more.

NEWSLETTER NEWS — This is one I’ve been meaning to mention for quite a few weeks now: Jamie Bradburn, who you’ll know if you’re a long-time subscriber since links to his history writing often appears in this section, has a new newsletter! You can read more here or subscribe here:

WEIRD MONEY NEWS — Irish Mae Silvestre shares the odd tale of Canada’s old twenty-five-cent bills, introduced at the same time the government was buying up American coins and shipping them out of the country. Read more.

SHOE NEWS — The Bata Shoe Museum got some international love last week, with a big piece from Radio Prague International. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

ON THE EDGE OF A CITY: TORONTO IN 1833 WALKING TOUR

August 19 — 10:30am — Meet at St. James Cathedral — Town of York Historical Society

“In this walking tour, explore the surviving built environment of the original 10 blocks of Toronto and discover how the Town of York, which started with a population of a couple hundred residents, became the City of Toronto in 1834, with a population of just under 10,000.”

$17.31 for non-members; $11.98 for members

DEATH, VIOLENCE & SCANDAL IN YORK WALKING TOUR

August 19 — 2pm — Meet at St. James Cathedral — Town of York Historical Society

“In this walking tour, explore the scandalous side of Little Muddy York as we walk through the surviving built environment of the original 10 blocks of Toronto and learn about the intriguing stories that would have been the gossip of the day.”

$17.31 for non-members; $11.98 for members

MR. DRESSUP TO DEGRASSI: 42 YEARS OF LEGENDARY TORONTO KIDS TV

Until August 19 — Wed to Sat, 12pm to 6pm — 401 Richmond — Myseum

“The TV shows of your childhood hit closer to home than you might think. From 1952 to 1994, Toronto was a global player in a golden era of children’s television programming. For over four decades, our city brought together innovative thought leaders, passionate creators and unexpected collaborations – forming a corner of the television industry unlike any other in the world. Toronto etched itself into our collective consciousness with shows like Mr. Dressup, Today’s Special, The Friendly Giant, Polka Dot Door, Degrassi, and more. Journey through Toronto’s heyday of children’s TV shows in this playful exhibition.”

Free!

ROOT OF THE TONGUE BY STEVEN BECKLY

Until August 27 — Wed to Sun, 11am to 5pm — Montgomery’s Inn

“Root of the Tongue is an exhibition of new artworks by Steven Beckly. Situated within Montgomery’s Inn, it consists of evocative images, sounds, and sculptural objects inspired by the Chung family, Chinese market gardeners who resided there in the 1940s. Considering their intimate roots to the site as well as the racism and xenophobia they faced during that time in Canada, Root of the Tongue explores the vegetable garden as fertile grounds for rituals of care and cultivation, ripe with symbolism and queerness.”

Free!

Hi Adam,

True story: my paternal grandfather's second wife, Bessie Carrol, was responsible for the death of Maggie Mick in 1925. I've been wanting to write about her life so I've been collecting articles etc. and doing genealogical research. What a coincidence to read your story about Lizzie Lessard and her attempted murder of Maggie Mick.