The Man Who Risked His Life for the Eclipse

Plus strange and shocking murders, a weird Mother's Day tour, and more...

Toronto was brimming with anticipation. The city was about to find itself in the path of a solar eclipse. On a winter morning in 1925, it would be in the full shadow of the totality — a rare celestial moment only made possible by one of the most incredible coincidences in the solar system: that our moon is exactly right size and exactly the right distance away to block out the sun while leaving a spectacular view of the corona.

In the days leading up to the eclipse, Toronto's newspapers were filled with advice on how best to view the astronomical marvel. Thousands of tinted glasses and smoked films were being sold as people excitedly made their plans. Parks, bridges and the waterfront all promised to be particularly popular. At least one hotel was offering customers a rooftop breakfast party.

Many local employers planned to give their staff time off to witness the event. "We wouldn't be able to keep our employees inside the store if we wanted to," one explained. The big downtown department stores of Eaton's and Simpson's would open an hour later than usual. Bank towers would let staff up onto their roofs. Even jewelry stores were going to allow their workers to watch — but only in carefully orchestrated shifts, just in case any local burglars were planning eclipse-inspired heists.

But when that January day finally did roll around, Toronto woke to disappointment. That winter morning was dreary and overcast. A thick blanket of cloud hung above the city. It completely blocked the view. A few people would catch momentary glimpses of the partial eclipse through the shifting cloud, but not of the climactic moment itself; no one on the ground in Toronto would get to witness the totality.

One man, however, wasn't ready to give up. He was determined to do everything he possibly could to see the eclipse, clouds be damned. And if that meant a daredevil mission that might put his own life in danger… well, so be it.

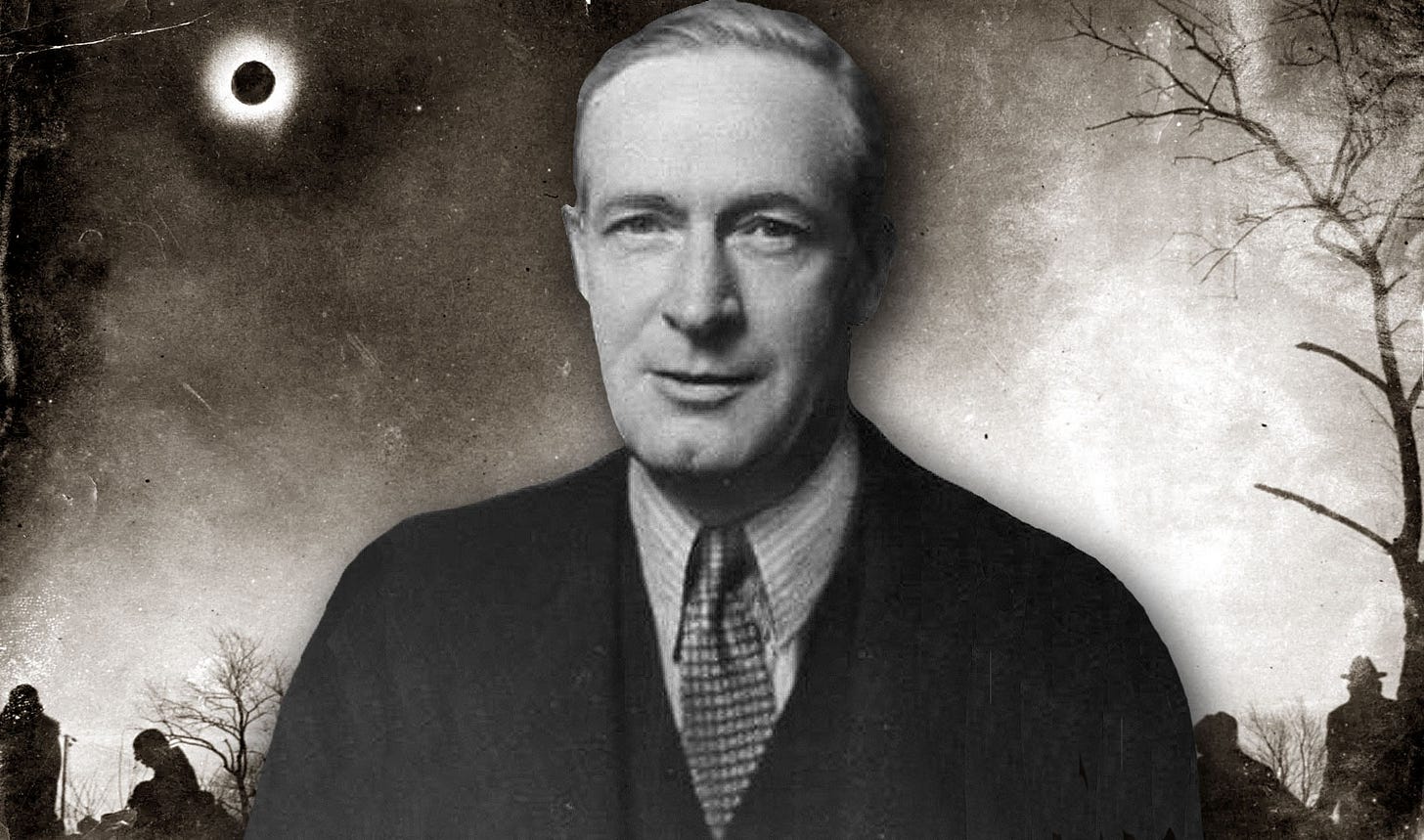

His name was Fred Griffin. He was a reporter at The Toronto Daily Star; one of the legendary old ink-stained scribes from the days when Ernest Hemingway and Morley Callaghan had desks in the newsroom. And while everyone else in the city was doomed to miss the eclipse, he had a plan to see it.

The newspaper had convinced the Royal Canadian Air Force to take Griffin up in one of their airplanes, hoping to fly so high they'd break through the clouds and come out the top with a clear view of the heavens. They could snap a photograph for the front page and get an eye-witness account from Griffin to publish alongside it. Torontonians might not be able to see the spectacular phenomenon for themselves, but at least they'd be able to hear it about from one of their own.

The morning of the eclipse, Griffin woke before dawn. He'd spent the night at Camp Borden, north of the city, where a pair of biplanes was being prepared for his mission. One would carry the reporter; the other, an air force photographer with a camera. When Griffin had gone to sleep the night before, the sky had been clear and full of stars. But even in the pre-dawn darkness, he could tell that a thick layer of cloud had rolled in. He must have known instantly that his role in the day's proceedings had just become vitally important. His mission was Toronto's only hope.

It wouldn't be easy to pull off. Airplanes were still a remarkably new invention. It had only been about twenty years since the Wright Brothers' first flight; even less since the first Canadian airplane had made a rickety take off in Cape Breton. Our country's first commercial airline was still more than a decade away. The biplane Griffin would be riding into the sky couldn't fly much higher than ten thousand feet — and that might not be enough. The experienced airmen at Camp Borden figured the ominous bank of clouds might very well reach higher than that. And there was a threateningly strong wind blowing, too.

Griffin's pilot was worried. He'd done a quick test flight that morning and it hadn't gone well. His plane might not be up for the challenge. "She's spitting like a devil," he reported. As they prepared for takeoff, he asked the ground crew to get another airplane ready — a backup just in case the weather forced them down out of the sky prematurely.

He was right to be concerned.

Still, Fred Griffin wouldn't be deterred. He was willing to go to great lengths to get his story. During the Second World War, he would risk his life reporting from some of the most notorious battlefields on earth. This was nothing. At eight o'clock sharp — as soon as everything was ready; the oil warmed, the engine tuned — the biplane roared down the runway and lifted off into the sky with the reporter aboard. The plan was simple: they would fly south to Toronto, getting higher and higher until they broke through the clouds and bore witness to the marvel above.

Things didn't get off to a promising start. "The sky was overcast and cheerless," Griffin wrote. "There was not a sign of the sun anywhere. On all sides there was nothing but overhanging clouds." The wind was slowing them down and forcing them to fly low. The air was bitterly cold. He was bundled up against it so tightly he could barely move. A fur-lined coat and cap. A facemask and a big scarf. Countless sweaters. Four pairs of socks and two pairs of mittens (one wool, one fur). He kept taking them off to try to take notes, but struggled in the cold and the wind.

"When we got up in the air the country stretched on all sides of us white and grim, with dark patches of bush and swamp and with the fences cutting irregular black lines on the surface. To the south and west the horizon was hidden in blue-black clouds, which hung low and menacing, cutting off the sight. It was a cold, dreary, and utterly depressing landscape from the air. But the plane went along singing gaily, the note of its tune only changing with a shift of the wind, and its stays vibrating like living chords."

They soared above Alliston and Bradford and the Holland River, making slow progress as they flew against the wind. Griffin eventually caught sight of faint touches of orange in the clouds above, a hint the sun was out there somewhere. The sky was full of mirages that day, but eventually he could tell the light was beginning to dim. The eclipse was underway. The moment of totality was drawing near.

That's when disaster struck.

Suddenly, the engine began to misfire. A connecting rod was broken and had smashed through one of the cylinders. The engine stuttered ominously… and then, it died.

They were still sailing through the air a thousand feet above the frozen ground, but now there was nothing keeping them up there. The plane began falling from the sky.

"We're through," the pilot reported.

The hunt for the eclipse had just become a life-threatening ordeal.

Thankfully, that pilot was an experienced flyer. Flight lieutenant Roy Grandy had fought in the First World War, flying dangerous missions over the front lines of France. Legion Magazine recently listed him among the greatest Canadian aviators of all-time. He knew how to bring his plane down safely. He banked it to one side, and then the other, drawing a big curve through the sky as they descended from the heavens. A moment later, they were making a rough landing in a snowy farmer's field a few kilometres north of Newmarket.

Griffin still didn't give up. They held out hope they'd be able to get back up into the sky if they could contact Camp Borden and get them to bring another plane. Together, they trudged through the snow for more than a kilometre before reaching the nearest farm with a telephone. It took them a while to get through; the operators had to patch them in via Barrie. "Gradually," Griffin wrote, "the minutes slipped away."

They'd missed their chance.

In the end, when the climactic moment came, they were standing under a tree at the edge of a valley, with a sweeping view of the snowy fields and the overcast sky. "It was a lonely scene of winter desolation," Griffin told the readers of The Star. "At last, the eclipse such as it was came, a mere flash of darkness." They hadn't even reached the path of the totality.

And so, it was all down to the second plane — the one with the photographer. Griffin had watched it soar past them during their flight. It had a more powerful engine, so even though it was weighed down by the heavy camera, it was faster and flew higher. He'd watched it disappear into the clouds not long before the emergency landing.

That second plane had flown straight down Yonge Street as it headed toward the city. Its pilot was another notable figure: George Brookes would go on to command Canada's bomber group during WWII. At first, he kept low to avoid being slowed down by the wind. But as they reached Richmond Hill, he began to climb. "We hit the clouds very suddenly," he told The Star, "and lost the earth entirely… Those clouds were thicker than we had ever expected. It was nearly eclipse time, and we kept on climbing, against time."

When they reached an altitude of eight thousand feet, they were still lost in the clouds somewhere high above Toronto. That's when the light began to fade. It was beginning. They kept climbing and climbing, desperately racing to break free from the clouds, but it all happened so quickly. It took less than a minute before they were plunged into total darkness. It was so dark, Brookes couldn't even read his controls.

The totality had arrived. But the clouds still hadn't given way.

And so, the second plane missed the moment too.

It wasn't until the darkness began to recede that they finally got their first glimpse of the eclipse. "Just as we were back to daylight once more we came into a little semi-circular patch of cloud," Brookes remembered. "It wasn't absolutely clear — we saw, sort of through a film, [a] very, very faint streak of the sun. Just a slender crescent, but glowing very clearly and distinctly. Really an impressive sight."

The photographer sprang into action. Alan Murfee was no stranger to stressful situations, either. He, too, had fought in the First World War; he would go on to become the first pilot in the world to have a woman give birth during one of his flights. As the biplane banked and put the sun behind them, he spun around in his seat, half-kneeling on it as he began to shoot.

By then, they were reaching the upper limits of the plane's capabilities, more than nine thousand feet in the air. It would be a long drop if he slipped. But for the next few precious minutes, he focused on the task at hand — firing off a shot every time he could get a brief glimpse through the clouds. He managed to get half a dozen photographs before they were finally swallowed up again and they began their descent to land on the ice of Toronto Bay.

The four men on board those two planes had done everything they could to give Torontonians a look at the spectacular event taking place above their city. They had stubbornly pushed the outer limits of what was possible. But try as they might, the eclipse had defeated them. They'd missed the totality and never quite cleared the clouds to get a completely clean shot.

So, in the end, this is the photograph that appeared on the front page of The Toronto Daily Star — the city's best view of the eclipse:

I also shared a shorter version of this story as part of my Weird Toronto History radio segment this week on Newstalk 1010. You can listen to that here.

In that interview, I also talked about how Toronto has been visited by Halley’s Comet three times since the city was founded, sparking terror and chaos. I wrote about that in the newsletter here.

And if you’d like another dramatic tale from the early days of Toronto aviation, I shared one in the newsletter last summer. You can read “A Lovestruck French Aristocrat in the Skies Above Toronto” here.

Looking Back At A Memorable Home Opener

This Monday is one of the biggest days on Toronto’s baseball calendar: the Blue Jays’ home opener at the SkyDome. And so, this seems like the perfect time to share a snapshot from a particularly memorable home opener held more than half a century ago. This photograph was taken on opening day at Maple Leaf Stadium back in 1961.

The Leafs played in the International League — one of the big minor leagues — and it really was international. The Toronto team had opened that season on the road in San Juan, Puerto Rico. And for a while, there was a team in Havana, Cuba, too. It meant the Leafs didn't play at home that year until the first week of May, though it still managed to snow during their practice the day before.

The cold weather doesn’t seem to have cooled off their bats. They took on the amazingly-named Jersey City Jerseys and crushed them 15–3. The victory came on the strength of a ten-run outburst in the 8th inning that included two grand slams. One of them was hit by switch hitter Ellis Burton who also hit a second home run that inning — one from each side of the plate!

"We never scored that many runs in a week last year," quipped second baseman Sparky Anderson (the future Hall of Fame manager). Guest of honour Branch Rickey called it, "Unbelievable."

Rickey’s presence at the game, however, was a reminder that the Leafs’ days were numbered. He was the former general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers; the man who recruited Jackie Robinson and helped break the colour barrier. He knew the Leafs’ owner very well. Jack Kent Cooke was an eccentric millionaire who had teamed up with Rickey in a plan to create a new major league to rival the American and National Leagues. The Continental League would have included a team from Toronto — our first big league club. But less than a year before this photo was taken, the plan had fallen apart and the proposed league was disbanded.

Cooke had long been determined to bring big league baseball to Toronto, but his patience was clearly running out. By the end of 1960, his gaze had begun turning toward the United States.

So, on the eve of that home opener in 1961, the future of baseball in our town was looking dim. The night before the game, they held a big "Meet The Ball Club" dinner at the Royal York Hotel. The guest of honour at the banquet was Jackie Robinson, who appeared alongside fellow Hall of Famer Lefty Grove.

Robinson gave a speech that night, taking it as an opportunity to talk about the elephant in the room. “When you lose a ballclub,” he cautioned, “you lose part of a city.”

Cooke doesn’t seem to have been listening. That same year, he left Toronto for the United States, where he’d go on to own the LA Lakers and Kings, the football team in Washington, evne the iconic Chrysler Building in New York. He soon sold the Leafs. They struggled on for a few more seasons after that, kept alive by diehard fans who invested their own money in the team, but by the end of the 1960s the club had left for Kentucky.

For a decade, Toronto had no big local ball team. It wasn’t until this day in 1977 that professional baseball finally return with the first ever Jays home opener. And with that snowy April day 47 years ago, a new era in the city’s baseball history began.

So, whether or not the Blue Jays can hit a lick this year, the home opener is always a moment to be celebrated. It’s a day that shouldn’t be about the owners or the brass, but about the dedicated fans who’ve made our city a baseball hotspot for the last 150 years.

Two More Events Added To The Festival of Bizarre Toronto History Line-Up!

Last week I told you all about the first two events I’ve added to the line-up for this year’s Festival of Bizarre Toronto History. On the Saturday afternoon, we’ll be taking A Bizarre Tour of the Necropolis Cemetery with Chantal Morris of Toronto Cemetery Tours. And on the Friday night, I’ll be sharing my own brand new lecture about The Body Snatchers of Toronto and how they once stalked our city’s graveyards.

This week, I’m very excited to announce two more events that will be part of the festival this year:

A Night of Strange & Shocking Murders!

Toronto's past is filled with chilling crimes that have a lot to teach us about the history of the place we call home. On the festival’s opening night, we'll dive into some of those grisly cases with three authors who've written about some of the strangest and most shocking murders in our city's history.

Nate Hendley is the Toronto-based author of several history books, including The Beatle Bandit: A Serial Bank Robber's Deadly Heist, a Cross-Country Manhunt, and the Insanity Plea that Shook the Nation and The Boy on the Bicycle: A Forgotten Case of Wrongful Conviction in Toronto. Carolyn Whitzman is a writer, researcher and Invited Professor at the University of Ottawa. Her most recent book is Clara at the Door with a Revolver: The Scandalous Black Suspect, the Exemplary White Son, and the Murder That Shocked Toronto. Adam Selzer is a tour guide and historian in Chicago and New York as well as the author of more than twenty books, including H. H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil.

Monday, May 6 at 8pm — held over Zoom

A Weird Toronto Mother’s Day Walk

The festival’s final day will be Mother’s Day. So what better time to take a tour filled with some strange stories about moms from the history of Toronto. We’ll explore everything from William Lyon Mackenzie’s elderly mother facing down soldiers during his infamous rebellion, to Mary Pickford’s mom raising a family filled with scandalous child stars.

I’ll be leading this tour myself!

Sunday, May 12 at 1pm

I’m still hard at work putting together the full line-up, so I’ll have lots more details to announce in the weeks to come!

GET YOUR FESTIVAL TICKETS HERE

Even if you can’t attend the festival, you can still support my work. The Toronto History Weekly needs your help! The number of paid subscriptions is verrrry slowwwwly creeping up, but since this newsletter involves a ton of work every week, it’s only by growing the number of paid subscriptions that I’ll be able to continue doing it. Thank you so, so much to everyone who already has — and if you’d to make the switch yourself, you can do it by clicking right here:

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

ICON NEWS — A new documentary about Jackie Shane — who wasn’t just one of the greatest soul singers in Toronto during the 1960s, but also a Black trans woman who spoke openly about her sexuality on stage — is getting its Toronto premiere at Hot Docs! I’ve already got my tickets and will post the full details as part of the event listings below. Read more.

LOST RIVERS MAP — The CBC’s Jaela Bernstien and Emily Chung have an incredible new interactive piece that looks at the hidden waterways buried beneath Canadian cities, including Toronto. Read more.

MEGA SPA NEWS — The group fighting to save Ontario Place’s west island from the Therme mega spa development won a legal victory in court last week. Ontario Place For All filed a court application late last year trying to require the provincial government to conduct an environmental assessment of the incredibly precious wildlife habitat. The government tried to get the case thrown out, but failed. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

A SLICE OF TORONTO HISTORY: HOW ETOBICOKE HELPED POPULARIZE PIZZA 1950–1990

April 18 — 7:30pm — Montgomery’s Inn — Etobicoke Historical Society

“Pizza is far more than its constituent parts of dough, sauce, and cheese; it is used by Alexander Hughes as a lens to explore the history of immigration, business, labour, urbanization, gender, culture, economics, consumption, and food in Toronto. The commodification of pizza, the development of pizza industries, and the culture of consumption in Canada paralleled currents of postwar life in Toronto. How did culture, ethnicity, immigration, and urban economies shape the commodification of pizza, an ethnic food once confined to the food ways of Italian immigrants? And what role did Etobicoke play in shaping the commodification of pizza?”

Free for members; annual memberships at $25

NEW DISCOVERIES DOWN BY THE BAY AT THE ASHBRIDGE ESTATE

April 24 — 7pm — The Beaches Sandbox — The Beach and East Toronto Historical Society

The Beach and East Toronto Historical Society in partnership with the Beaches Sandbox present Dena Doroszenko, senior archaeologist with the Ontario Heritage Trust, for a talk about new discoveries made down by the bay at the Ashbridge Estate.

Free!

THE TORONTO PREMIER OF “ANY OTHER WAY: THE JACKIE SHANE STORY”

April 27 (9pm) & April 28 (8:45pm) — The TIFF Lightbox — Hot Docs

“Once you’ve heard Jackie Shane sing, you’ll never forget it. Yet, after shattering barriers as one of pop music’s first Black trans performers, this trail-blazing icon vanished from the spotlight at the height of her fame. From modest beginnings in Nashville, Shane soon recognized her talents and, in her late teens, made her way to Boston and Montreal, working the nightclub circuit while taking the stage with Frank Motley, a musician known for playing two trumpets at once. Her arrival in Toronto during its 1960s music explosion made her a highly sought-after headlining act who seemed destined to take her place among the R&B stars of the era. Blending her music with never-released phone conversations and soulful animated re-enactments, Any Other Way: The Jackie Shane Story brings Shane back to life in her own words, finally providing the recognition she so rightly deserves and introducing her to a generation fighting for their right to be their true selves.”

$17.70