The Man Who Mailed Himself Out Of Slavery

Plus the city's strange hockey roots, my baseball course is back, and more...

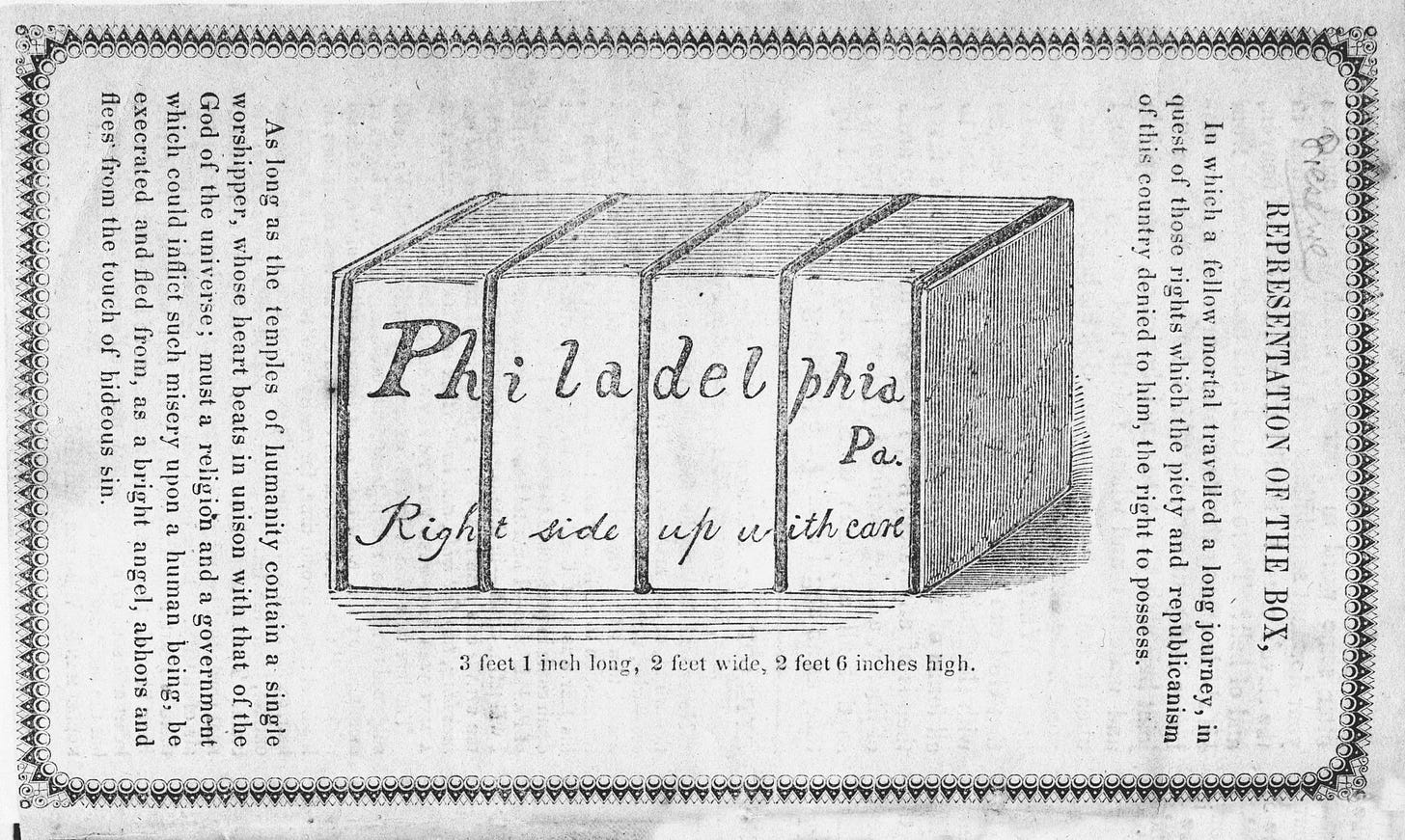

It wasn't a very big box. A wooden crate just three feet across, two feet deep and two-and-a-half high. It had been nailed shut. It was labelled as dry goods and marked "Philadelphia, PA: This Side Up With Care." It looked like quite an ordinary postal shipping container. The only clue there was something unusual within it seems to have been a trio of small holes drilled through the wood — the air holes that would keep the man inside from suffocating during the harrowing journey to come.

His name was Henry Brown. He'd been born into slavery on a plantation in Virginia. He grew up there over the course of the early 1800s, eventually getting permission to get married and start a family of his own with his wife, Nancy. But one of the men who enslaved her was particularly cruel. Despite the fact he'd been extorting Brown for money, demanding monthly payments in return for a promise not to "sell" Nancy and the children, that's exactly what he did.

Brown was in his early thirties when it happened. He watched in horror as his family was taken off to North Carolina as part of a bleak procession: hundreds of enslaved people on a forced march through the streets of Richmond, the adults in ropes and chains, his eldest child calling out for him as they were taken away. As Nancy passed the spot where he was standing, Henry couldn't hold back. He stepped forward to take her hand and walked by her side for a few miles. Neither of them said a word; they were both too overcome to speak. "When at last we were obliged to part," he later wrote, "the look of mutual love which we exchanged was all the token which we could give each other that we should yet meet in heaven." She was pregnant with their fourth child. They would never see each other again.

That's when he became determined to escape. He began to spend much of his time thinking about freedom and how to reach it. He wasn't sure how he would manage it, but he became more and more convinced that it was only a matter of time before he did.

The idea finally came to him out of the blue. One day, he felt compelled to pause his work and pray. "I felt my soul called out to heaven to breathe a prayer to Almighty God," he explained. "I prayed fervently… when the idea suddenly flashed across my mind of shutting myself up in a box, and getting myself conveyed as dry goods to a free state."

He would mail himself to freedom.

It was an incredibly risky plan, absurdly dangerous, but his mind was made up. "I was willing to dare even death itself rather than endure any longer the clanking of those galling chains," he wrote. With the help of a friend and a sympathetic white shopkeeper who was paid for his assistance, Brown fleshed out his plan and began the preparations. He bought a box from a carpenter. Found someone in Philadelphia willing to receive the package. And then he used sulfuric acid to burn his finger to the bone so he could ask for time off to recover; it would give him a few days before his disappearance aroused any suspicions. With that, he was ready.

It was before dawn on a March morning in 1849 that Henry Brown climbed into his box. With him, he carried a bladder of water and a small drill — something he could use in case those three air holes weren't enough. Then, his friends nailed down the lid and took him off to the post office.

The next 27 hours would be torture. The label declaring "This Side Up With Care" was immediately ignored; Brown tumbled upside-down inside the box as it was loaded into a wagon and taken to the rail depot; then, he was pitched onto his side, roughly tossed onto a waiting train. Next, he was loaded onto a steamboat and shipped up the Potomac River. He found himself upside-down yet again, this time stuck in that position for more than an hour. The pain of it was nearly overwhelming, but he was determined to push through, to keep quiet, to keep going.

"I was resolved to conquer or die," he later remembered. "I felt my eyes swelling as if they would burst from their sockets; and the veins on my temples were dreadfully distended with pressure of blood upon my head.… I felt a cold sweat coming over me which seemed to be a warning that death was about to terminate my earthly miseries, but as I feared even that less than slavery, I resolved to submit to the will of God."

His prayers were finally answered after 90 minutes. When a couple of passengers got tired of standing, they rolled his box over and sat down on it. He was finally right-side-up. He listened, amused, as they wondered aloud what might be inside the crate. It was the mail, they figured. Brown would later joke that it was indeed a male, just not the kind they were thinking.

When the steamboat reached Washington, the box was loaded onto another wagon, taken to another train. Two workers debated whether to heed the "This Side Up" warning. One figured it didn’t matter if they broke whatever was inside, the railway company would pay for it. "No sooner were these words spoken," Brown wrote, "than I began to tumble from the wagon, and falling on the end where my head was, I could hear my neck give a crack, as if it had been snapped asunder and I was knocked completely insensible."

He came to just in time to get thrown onto the train, upside-down once again for a while before his box shifted. But now, he was finally on the last leg of his journey. Before long, he heard the words he'd been waiting for: "We are in port and at Philadelphia." His heart leapt for joy. He was in Pennsylvania. A free state. He'd made it.

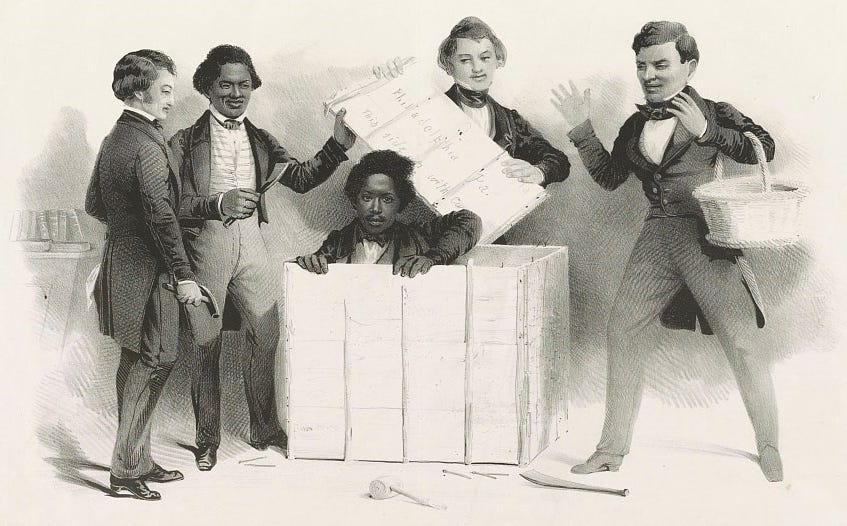

It had taken more than a full day and a voyage of hundreds of kilometres, but now all he had to do was wait. He sat silently in his box until the man he'd been mailed to came to pick up the package. Passmore Williamson was a merchant, a Quaker and a dedicated abolitionist, a member of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee — part of the Underground Railroad. Williamson took the box home and carried it into his house, where a small group of supporters gathered around the crate unsure of how to proceed.

Eventually, one of them knocked on the wood. "Is all right within?" he asked tentatively. "All right," came the reply. As they broke open the box, Henry Brown stepped out into the light — and into freedom. "My resurrection," as he put it, "from the grave of slavery."

“How do you do, gentlemen?” he's said to have casually asked — and then, promptly fainted.

It would be many years before Brown moved to Toronto. His extraordinary tale made him instantly famous. Now calling himself Henry Box Brown in honour of his escape, he spent the rest of his life as a performer touring across the United States, Canada and Britain.

His shows were a eclectic blend of memoir, advocacy, and spectacle. He loved to perform magic tricks and illusions, lectured on mesmerism and hypnotized audience members. His reputation as an escape artist had, of course, already been well-established. According to historian Martha J. Cutter his stage act was "an ever-changing, innovative performance art that melded theatre, street shows, magic, painting, singing, print culture, visual imagery, acting, mesmerism, and even medical treatments."

But while he drew big crowds on the promise of entertainment and sensationalism, Brown also used his shows as a chance to confront his audience with the realities of slavery. He toured with a panorama called Henry Box Brown's Mirror of Slavery: forty-nine scenes painted on an enormous canvas scroll, towering eight or ten feet high. He spoke and wrote about his experiences. At least once, he even re-enacted his journey as part of a tour — carried from town to town inside a replica of his box so he could dramatically emerge at the beginning of his performance.

It wasn't until the end of his life that he settled down in Toronto, a town with its own history of slavery. In the years after our city was founded, local families like the Russells and the Jarvises enslaved families like the Pompadours here. It would take decades for slavery to be phased out in what's now Ontario; it wasn't abolished until the 1830s. Toronto would then become an important stop at the end of the Underground Railroad. People like Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, who'd escaped slavery themselves, worked hard to make the city a more welcoming place for those who followed in their footsteps.

Brown arrived in the 1880s. By then, he was an old man. He had never been reunited with Nancy and their children, but he had been able to start a new family with a new wife; he even incorporated them into his act. He moved into Corktown, living in one of the handsome Victorian row houses on Bright Street; it's still standing there now. He would spend the final decade of his life in our city. We don't know much about those years, but it seems likely he continued performing. He listed his profession in city records as "Lecturer," "Traveller" and “Professor of Animal Magnetism."

Even then, his performances would have been powerful acts of resistance. Despite attempts by Black Torontonians to have them banned, racist minstrel shows were still popular. White performers regularly donned blackface in our city, perpetuating hateful stereotypes and romanticizing slavery. As Cutter explains, Brown's shows might have been sensational, but they were also a reminder of the reality of slavery — a Black performer speaking in his own words about his own experiences.

Henry Box Brown finally passed away in Toronto in 1897, half a century after he made his dramatic escape. He was laid to rest in the Necropolis Cemetery in Cabbagetown, where you'll still find him today. And last week, he was officially honoured by his adopted home. The City of Toronto has named the alleyway that runs behind his old house as Henry Box Brown Lane.

For a long time, it seems people weren't sure what had happened to Henry Box Brown at the end of his life. It was historian Martha J. Cutter who tracked down the evidence that he'd spent his final years here in Toronto. She shared her findings in a fascinating article about his performances — and the meaning and symbolism behind them — called "Will The Real Henry Box Brown Please Stand Up?" You can read it here.

Thank you so much to everyone who supports The Toronto History Weekly with a few dollars a month! The newsletter has nearly 3,200 subscribers, but only 117 people have made the switch to a paid subscription — so I very much appreciate those of you who have! It’s a ton of work putting this together every week, so it’s only thanks to your support — and by continuing to grow that number — that I’m able to continue doing it. If you haven’t already made the switch but would like to, you can do it by clicking right here:

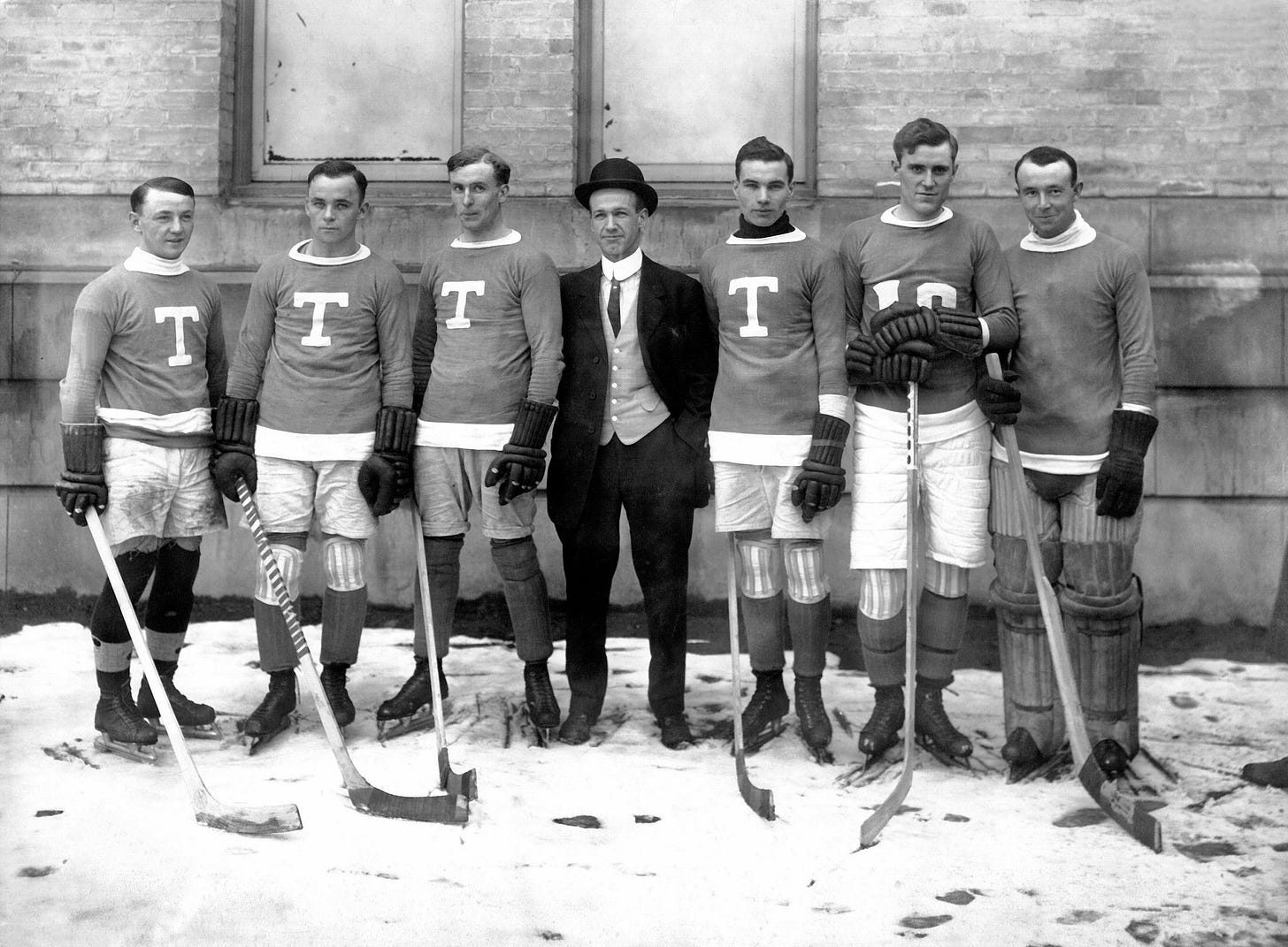

The Strange Roots of Hockey in Toronto

With the NHL All-Star Game in town this week, I thought I should fill my “Weird Toronto History” radio segment with some of the strange hockey stories from the city’s past — all of them from our Toronto sports history exhibit at Myseum (which you can learn more about here if you haven’t already checked it out). Most of the weird tales I shared are from more than a century ago, an era before the Maple Leafs existed — including the story of how the NHL was founded out of hatred for the owner of Toronto’s big hockey team at the time, The Blueshirts.

You can listen to my “Weird Toronto History” segments on Newstalk 1010’s The Rush every Tuesday afternoon at 3:20pm. And you can listen to last week’s strange hockey stories right here:

My Baseball Course Is Back!

There are still a few weeks left before our Toronto sports history exhibit closes at Myseum — and with the Blue Jays’ spring training also about to kick off, we’ve decided the best way to celebrate is by bringing back my online course about the history of baseball in Toronto.

We’re offering it as a Myseum Masterclass called The History of Baseball in Toronto: From Sandlot to SkyDome with Adam Bunch. It’ll begin on February 20 and run every Tuesday night at 7pm on Zoom until March 12. Registrations are $75 (plus Eventbrite fees) and will help support Myseum in all the amazing work they do.

Here’s the full course description:

Baseball was being played in Toronto more than a century before the Blue Jays were born.

In this online course, we'll explore the game's evolution in our city — from the days when it was a working class sport played by "undesirables" to Joe Carter jumping for joy in front of 50,000 screaming fans.

Along the way, we'll meet everyone from con artists and kidnappers to eccentric millionaires and feminist icons — the people who've made Toronto baseball what it is… and helped transform our city in the process.

I’ve Got Four Upcoming Talks!

I’ve got a busy couple of months coming up, including a few talks that I’m giving for local historical societies. They’re all open to the public, so I thought I’d let you know all the details in case you’d like to check any of them out…

THE TORONTO BOOK OF LOVE & THE CITY’S ROMANTIC PAST

Saturday, February 10 — 1pm || I’ll be talking about The Toronto Book of Love for the York Pioneer & Historical Society at Friends House (10 Lowther Avenue). Tickets are $25 and there will be a light lunch provided, too. Learn more.

THE TORONTO BOOK OF LOVE & THE CITY’S ROMANTIC PAST

Wednesday, February 21 — 7pm || I’ll also be talking about The Toronto Book of Love for the North York Historical Society a couple of weeks later at the North York Central Library (5120 Yonge Street). It’s free with registration. Learn more.

UNVEILING TORONTO’S ARCHITECTURAL TAPESTRY

Thursday, March 7 — 6pm || I’ll be part of this year’s annual fundraiser for the Town of York Historical Society and Toronto’s First Post Office, sharing some of my favourite stories about artists and architects from our city’s past. The event will also include presentations from artist Summer Leigh and architect Alessandro Tersigni, along with a silent auction, a pop-up stationary shop with local vendors, a pop-up art exhibition, and food and drink for sale. It’s being held in the Great Room of St. Lawrence Hall (157 King Street East), which is a spectacularly beautiful space. Learn more.

TORONTO’S FOUNDING DOG & HOW HE ALMOST GOT EATEN

Thursday, March 14 — 7:30pm || I’ll be delivering the 2024 Howland Lecture at Lambton House (4066 Old Dundas Street) for Heritage York. It will be a talk about our city’s founding canine, Jack Sharp, and how the big Newfoundland got himself into some very deep trouble. Learn more.

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

CLANG CLANG WENT THE TROLLEY NEWS — Grade 11 student Luka Jovanovic has created a neat interactive map that shows us what Toronto’s streetcar network looked like back in 1945. Kimia Afshar Mehrabi interviewed him for blogTO. Read more.

CITY OF THE DEAD NEWS — Jonsaba Jabbi shares stories about some of the Black Torontonians buried in the Necropolis Cemetery, including the Blackburns and Albert Jackson. Read more.

JUST ONCE BEFORE I DIE NEWS — The seven living members of the last Maple Leafs team to win the Stanley Cup were honoured at the NHL All-Star Game this week. Dave Stubbs talked to them about their memories of that championship run. Read more.

ALREADY A QUARTER OF A CENTURY AGO SOMEHOW NEWS — Nadia Sule takes a look back at the club scene in Toronto back around the turn of the millennium. Read more.

PEOPLE’S PRINCESS NEWS — Global News has a report about Casey And Diana, the new play from Soulpepper about Princess Di’s visit to the Casey House AIDS hospice back in 1991. Watch it.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

THE STORY OF WINDERMERE UNITED CHURCH — A SWANSEA LANDMARK FOR MORE THAN A CENUTRY

February 7 — 8pm — Online & In-Person at Swansea Town Hall — Swansea Historical Society

“Windermere United Church has played an important role in the life of the Swansea community ever since the congregation was founded in 1912, as Windermere Methodist Church. When the United Church of Canada was created in the 1920s, Windermere Methodist became Windermere United. For many decades, the congregation grew and prospered, and in recent years it was noted for its outreach initiatives. In 2023, as the membership was shrinking, the decision was made to merge with Runnymede United. We are pleased that the landmark building at the corner of Mayfield Avenue will be preserved as a hub for community-oriented activities, now known as the Windermere Campus of Runnymede United Church.”

Free, I believe!

JOSHUA GLOVER: ESCAPED SLAVE & ETOBICOKE PIONEER

February 15 — 7:30pm — Montgomery’s Inn — Etobicoke Historical Society

“Joshua Glover was born a slave in the American South. Sold in St. Louis, Missouri in 1850, he escaped and lived as a free man in Wisconsin for two years. When his former owner tried to reclaim him, a riot ensued as Abolitionists partially demolished a jail to free him. Joshua Glover then rode the Underground Railroad to a new life in Canada, establishing himself in the Township of Etobicoke. He worked for farmer Thomas Montgomery at Montgomery’s Inn and would marry twice. This is an account of slavery and the Abolitionist movement in the United States, the Underground Railroad and the life of a Black man in Etobicoke in the 1800s. Finally, we’ll look at how Joshua Glover has been remembered both in the United States and in Canada.”

Free for members; annual memberships are $25

LORNA POPLAK ON THE DON: THE STORY OF TORONTO’S MOST INFAMOUS JAIL

February 28 — 7pm — The Beaches Sandbox — The Beach & East Toronto Historical Society

“Conceived as a ‘palace for prisoners,’ the Don Jail never lived up to its promise. Although based on progressive nineteenth-century penal reform and architectural principles, the institution quickly deteriorated into a place of infamy where both inmates and staff were in constant danger of violence and death. Its mid-twentieth-century replacement, the New Don, soon became equally tainted.”

Free!

THE CURIOUS EVOLUTION OF RIVERDALE AVENUE

February 28 — The Riverdale Historical Society

Bob Georgiou of teh Scneexplores the history of the east end street.

Contact the Riverdale Historical Society for more info

ATROCITY ON THE ATLANTIC: THE LONG WAKE OF A FORGOTTEN WAR CRIME AGAINST A CANADIAN HOSPITAL SHIP

February 29 — 8:15pm — Toronto Reference Library

“On the evening of June 27, 1918, an unarmed, clearly marked Canadian hospital ship called the Llandovery Castle was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland by a German U-boat. Sinking hospital ships violated international treaties, so the submarine commander tried to kill the survivors to conceal his war crime. ... This presentation will discuss the attack, the survivors and the deceased, why the attack was forgotten, and the long aftermath of an atrocity that continues to impact military conduct and international law today.”

Free!

PRINTING MARY ANNE SHADD’S NEWSPAPER AT MACKENZIE HOUSE

Until February 29 — Various times daily, Wed to Sun — Mackenzie House

“Join Mackenzie House for a tribute to the life and work of Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the first Black woman to publish a newspaper in North America. In 1854, she was publishing her newspaper, The Provincial Freeman, on King Street in Toronto. Visitors are invited to print a copy of Mary Ann's newspaper on the 1845 press, customized with their name!”

Free!

BLACK DEFENDERS OF UPPER CANADA TOUR AT FORT YORK

Until February 29 — Various times daily, Wed to Sun — Fort York

“Discover the contributions made by Richard Pierpoint, and the Coloured Corps, in the defence of what is now Ontario during the War of 1812. Learn about the connections between global trade, global consumption and the African Diaspora through an exploration of ingredients used in the historic kitchen.”

Free!

LORNA POPLAK ON TORONTO’S DON JAIL

March 6 — 8pm — Swansea Town Hall & Online — Swansea Historical Society

“Lorna Poplak is a Toronto-based writer, editor, and researcher. She is the author of two award-nominated non-fiction books: — The Don – The Story of Toronto’s Infamous Jail, and Drop Dead – A Horrible History of Hanging in Canada. With these and other publications, Lorna is establishing herself as an authority on the history of crime and punishment in Canada. Her presentation will include many fascinating stories about people associated with the Don Jail – the inmates, the staff, the governors, people who escaped from the Don, and people whose lives ended there at the end of a rope.”

Free, I believe!

THE LIFE & TIMES OF ALFRED LAFFERTY

March 21 — 7:30pm — Montgomery’s Inn — The Etobicoke Historical Society

“In 1869 Alfred M. Lafferty, M.A., Richmond Hill, was a witness to the marriage of William Denis Lafferty, a black farmer who lived in Etobicoke. Who was the man with the same surname and a university degree? Hilary J. Dawson’s research uncovered the story of the Lafferty family, and the successes, challenges, and tragedies they faced. The Lafferty parents arrived from the United States in the 1830s as freedom-seekers and their two older sons later farmed in Etobicoke. The youngest son, Alfred, won prizes for excellence at both Upper Canada College and the University of Toronto. Alfred M. Lafferty would be the first black High School Principal in the province. Later, he became the first Canadian-born black lawyer in Ontario.”

Free for members; annual memberships cost $25