The Canadian Coronation Arch That Accidentally Landed A Blow Against The British Empire

Plus a fight over horse manure, one of the most expensive Canadian paintings ever, and more...

London was buzzing. It was the summer of 1902 and a new king was about to be crowned. Queen Victoria had died and her debaucherous party boy of a son, Bertie, was ascending to the throne as King Edward VII. His coronation would be even more extravagant than his mother's, with world leaders gathering from all over the globe, thousands of guests invited to the ceremony at Westminster Abbey, and tens of thousands of soldiers preparing to march lockstep through the streets. The centre of London was draped in fabric, flags and bunting. Businesses erected huge signs applauding the new king. The capital had gone all out, loudly proclaiming its love for its monarch and its empire.

And right at the heart of those celebrations stood one of the most spectacular sights of all: a massive new Canadian monument erected to profess our country's passionate devotion to the British Empire and to promote our own brand of colonialism. A gargantuan archway that was about to do the exact opposite of what it was designed to do. This towering mountain of Canadian kitsch was about to deliver a bloody blow against British imperialism.

The Canadian arch soared four storeys into the air, decked out in brilliant red and gold, capped by a pair of towers and an opulent crown-shaped dome. It was erected right in the middle of the coronation procession route — on Whitehall, the street that runs from Trafalgar Square to the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey, lined by government ministries. The arch commanded the middle of the road, spanning nearly its entire width, easily big enough to allow traffic to pass beneath it — horses, cyclists, pedestrians, even marching rows of soldiers. Flags fluttered from its heights. At night, it lit up with a magnificent glow. On coronation day, the carriage carrying the new king and queen would pass right through it. It promised to be one of the centrepieces of the event.

The arch was a very big deal for Canada. It was a physical manifestation of our country's optimism as the 1900s got underway. The prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, would soon give a speech at Massey Hall declaring that "the twentieth century shall be the century of Canada... For the next seventy years, nay for the next hundred years, Canada shall be the star towards which all men who love progress and freedom shall come." And the arch over Whitehall wasn't just meant to reflect that vision of the future, it was designed to help bring it about.

Just a few decades earlier, Canada had signed one of the biggest land deals in history — buying millions of square kilometres of land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, including the great plains at the centre of the continent. The federal government had spent much of the time since trying to push the Indigenous nations who'd been living there for thousands of years off that land. Residential schools were built. Tuberculosis was allowed to run rampant. Food was withheld. Plains bison were hunted nearly to extinction, until there wasn't a single one left alive in Canada. Indigenous traditions were banned. When people like Louis Riel resisted, troops were sent west. And European settlers flooded in, tasked with turning the great plains into the farmland of the Prairies.

The man responsible for attracting those settlers was Sir Clifford Sifton. He was the Minister of the Interior and Superintendent General for Indian Affairs, famous for aggressively pushing settlement on the plains — what his department called "The Last Best West." Advertising campaigns were rolled out. Immigration agents searched for potential new Canadians. Touring exhibitions touted the advantages of life out west.

Since Sifton had taken office, immigration into Canada had already quadrupled. But he wanted to keep it growing from there. So, his ministry came up with a plan. They would seize the opportunity presented by the coronation to erect a massive temporary monument right in the heart of the imperial capital. It wouldn’t just be a celebration of Canadian patriotism and a spectacular ode to the new king and queen, it would also serve as a giant advertisement for the colonization of the Prairies.

One side of the arch was emblazoned with a slogan in big bold golden letters:

CANADA

BRITAIN'S GRANARY

GOD SAVE OUR KING & QUEEN

And on the other side:

CANADA

FREE HOMES FOR MILLIONS

GOD SAVE OUR ROYAL FAMILY

The arch wasn't just decorated with portraits of the new monarch and his wife, but also with idealized scenes of life on the Canadian Prairies. And to top it all off, the monument was adorned with the bounty of those plains: covered in golden wheat and corn shipped in from Manitoba.

Thanks to its massive dimensions and its prominent location, the arch was impossible to miss. Anyone passing through Whitehall couldn't help but see it — and the message it carried. The arch was hailed as a resounding public relations success. The Globe called it "one of the most effective advertisements that Canada has had in Great Britain in her history… It has been described at length and in most glowing terms in practically every leading newspaper in Great Britain, it has been photographed by thousands upon thousands of kodak fiends, it has been gazed upon by the admiring eyes of millions, it has occupied a leading place in the illustrated journals of the great metropolis…"

But the arch would soon be making very different headlines — denounced as a life-threatening hazard after nearly killing one of the colonial authorities it was meant to impress.

It all began with a bit of bad luck for the king.

Queen Victoria had lived into her eighties, so King Edward was in his late fifties by the time she died and he ascended to the throne. As a prince, he'd earned a scandalous reputation as a hard drinker, heavy smoker, and wild partygoer. He even ordered the construction of a "love chair" to facilitate his desire to sleep with multiple women at once, and had it kept at his favourite Parisian brothel. That salacious lifestyle had taken a toll. His first few months on the throne were plagued by poor health. But when he fell seriously ill just two days before his coronation, it seems to have simply been an unlucky coincidence.

There had been signs something was wrong for a couple of weeks at that point. He'd been running a fever, pale, tired and grumpy. A slight ache in his stomach became a terrible, crippling pain. The king tried to avoid getting treatment, insisting he carry on with preparations for the coronation — even after a fortune teller told him he would die while accurately predicting her own death in the process, which came just a few days later. But in the end, the king was given no choice. His appendix had ruptured. One of his own doctors refused to follow his commands and demanded they operate. The risky surgery saved the king's life, but it meant the coronation couldn't possibly go ahead as planned. It would be delayed indefinitely.

But that extra time wouldn't be entirely wasted. With so many heads of state gathered in London, a big Colonial Conference was being held. It featured high-ranking government officials from across much of the British Empire, including the leaders of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland (still a separate colony back then), and South Africa's Cape Colony and Colony of Natal. Canada's delegation was led by prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier himself.

The meeting was being run by a guy named Joseph Chamberlain, the father of future prime minister Neville Chamberlain. He'd begun his political career as a radically liberal anti-imperialist before swinging to the right and allying himself with the Tories. As Secretary of State for the Colonies, he was the man responsible for managing the Empire. He's one of the key figures in the entire history of British imperialism, one of its most forceful champions.

Chamberlain had spent the last few years overseeing a brutal colonial war in South Africa. The Boers — descendants of Dutch settlers — had moved out of the British colonies there to establish their own independent states. The British were determined to take those new colonies for themselves, along with all the gold and diamonds inside them. And as the Great Boer War got underway with a series of stunning British defeats, Chamberlain called upon the colonies to send troops in support of the Empire.

Canada still saw itself as a deeply British country. It had been decades since Confederation, but it would still be more than half a century before we even got our own flag. While there was plenty of opposition to the war, especially among Irish-Catholics and in Québec, the vast majority of people living in cities like Toronto had British heritage. Many of them weren't just willing to fight for the Empire, they were eager. Thousands of Canadians answered Chamberlain's call.

The war was so deeply associated with the minister, some would call it "Joe's War." And in its later stages, it would take an especially horrifying turn. Thanks in part to those Canadian troops, the tide of the war had turned. Eventually imperial troops occupied the colonies with the Boers adopting guerrilla tactics to continue the fight. The British responded by targeting civilians with a scorched earth campaign and by opening more than a hundred camps where Boers and Black South Africans were held in deadly and dehumanizing conditions.

The authorities came up with a new name for these makeshift prisons: they called them “concentration camps.”

More than a quarter of the Boers who were held in the camps died there — nearly 28,000 of them, almost all children under the age of sixteen. In the camps for Black South Africans, at least another 23,000 people died. Future British prime minister David Lloyd George denounced it as "a policy of extermination." By the time the settlers were forced to surrender, the Great Boer War — more accurately called the South African War since it engulfed so many Black South Africans, too — had claimed more than 100,000 lives.

By then, the Canadian soldiers had already come home. In Toronto, they were met by a hero's welcome. There was a parade down King Street with cheering crowds and a canyon of buildings draped in bunting and the Union Jack. Even today, one of our city's most prominent monuments is dedicated to those who fought the Boers: the South African War Memorial stands in the middle of University Avenue at Queen, right outside Osgoode Station.

The war had ended just weeks before King Edward's coronation was scheduled to take place. And with his war over, Joseph Chamberlain was able to turn his attention on the Colonial Conference. He was using it as a chance to push for his dream of a more united British Empire, with an imperial parliament made up of representatives from across the colonies, free trade between them, and a unified defense force.

But his plans were about to receive a bloody setback thanks to the Canadian arch.

One evening about a week into the conference, Chamberlain climbed into a little horse-drawn hansom cab outside the House of Commons. He was on his way to one of the most prestigious gentlemen's clubs in London, the Athenaeum. Its members have included many of the most famous Britons in history, including Darwin, Dickens and Churchill. Even Sir John A. Macdonald was an honourary member, having downed more than a few drinks there during his frequent visits to England.

The club was just a short drive from parliament, a few blocks up Whitehall and around the corner. Which meant Chamberlain would be passing right through the Canadian arch. It must have only been a couple of minutes after the cab lurched into motion that it reached that towering behemoth of wheat, corn and patriotism. And that's where something went terribly wrong.

As the cab passed beneath the arch, the horse was spooked by the elaborate decorations — what one of Chamberlain's biographers called the "tinkling gewgaws." And since that summer day had been dry and hot, the street had been watered down to keep dust from kicking up. When the horse shied away from the arch, its hooves slipped on the wet pavement. The beast went down. The cab was suddenly pitched violently forward — and so was the politician inside it. Chamberlain was thrown forward. His head crashed against the front window, smashing the glass. It sliced a three-inch gash across his forehead with a second cut beneath his right eye, and shards of glass embedded in his flesh.

He stumbled out of the cab, deeply shaken, blood pouring down his face. As a crowd of concerned onlookers gathered, a police officer came to his aid, wrapping a handkerchief around his head and hurrying him off to the hospital. The wound was deep. Some reports suggest the glass cut all the way down to the bone and that the impact left a dent in his skull. In the hours to come, he would maintain his good humour — "I never knew I had so much blood to lose," he joked, filling his hospital room with cigar smoke — but the doctors thought he was in shock. It would be two days before they released him, and they ordered him to stay in bed for at least another two weeks beyond that. Some friends believed he never truly recovered from the accident.

He'd be back on his feet before long, disobeying the doctors, but at least for a while he was in no shape to host a series of highly stressful international negotiations. Thanks to the attack of the Canadian arch, the Colonial Conference had to be postponed.

It would pick up again in a couple of weeks, but Prime Minister Laurier and the other colonial leaders used the time to coordinate among themselves, presenting Chamberlain with a united front when the negotiations resumed. The colonies rejected his ideas. Instead, they would adopt a Canadian proposal for reduced tariffs. For Chamberlain, the conference was a bust — and the accident has been cited as one of the reasons he may have failed to achieve any of his big aims. His dream of a united British Empire would never come to pass.

In the wake of the accident, the Canadian arch came under plenty of public criticism. The commissioner of the London police force denounced it as a traffic hazard. The Canadian government was forced to try smooth things over by donating $250 to the police orphanage fund. But the monument still had plenty of fans. Just days later, the wheat and corn were removed in order to re-decorate it in honour of Lord Kitchener. The famous military commander who'd first proposed the concentration camps was returning from South Africa; the Canadian arch would hail him as a "HERO IN WAR AND PEACE". And when the grain was taken down, a rowdy crowd gathered to claim the crops as souvenirs, along with shrubs meant for the new display.

So the monument was still standing a few weeks later when King Edward had finally recovered enough to go ahead with the coronation. And as the royals' golden carriage travelled to and from Buckingham Palace — the same one Charles used to leave the abbey this weekend — they passed through the notorious Canadian arch as crowds cheered and waved.

Despite the controversy, the monument was declared a success. Sir Clifford Sifton's Prairie settlement scheme continued to gather momentum. By the time he resigned a few years later, immigration to Canada had doubled yet again — nearly ten times what it had been when he first took office. Alberta and Saskatchewan were added as provinces just three years after the coronation arch was raised over Whitehall.

In the decades that followed, many Canadians would continue to see themselves as proud subjects of the British Empire — even as that empire was being dismantled and its legacy widely questioned. It wasn't until the 1960s that Toronto erected a statue in honour of King Edward VII, who'd once paid a visit to our city as a prince. His monument is still there in Queen's Park, a park he opened, standing outside our provincial legislature. It's an equestrian statue that originally stood in Delhi, but was taken down after Indian independence. It was left to rot along with other imperial monuments in a forgotten corner of that city's Coronation Park — where the crowning of British monarchs was once celebrated — before eventually being shipped around the world to take a place of honour in our city instead.

More than a century after the coronation of King Edward VII, his statue still stands in the heart of Toronto — an object of colonial nostalgia, a target for anti-colonial protest, and a reminder of another monument that once stood in the heart of the imperial capital itself.

We shot a whole episode of our Canadian documentary series about the statue of King Edward VII. You can watch it here. We’ll also have a future episode that will touch on the story of Sir Clifford Sifton and the Prairies — I have to thank one of my co-creators, Kyle Cucco, for first telling me about him. If you’d like to learn more about the federal government’s campaign to push Indigenous people off the Prairies, I highly recommend Clearing The Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life by James Daschuk.

Two Strange Toronto Connections to Queen Victoria’s Coronation

This is my favourite image from Queen Victoria’s coronation. It shows us the moment when an elderly lord tripped on the steps up to her throne and rolled back down them, with the new queen leaping to his aid. But that isn’t even the strangest story involving the aptly named Lord Rolle. A couple of decades earlier, he’d faced off against the founder of Toronto in a struggle to determine who would lay claim to a huge amount of horse manure. It’s one of the stories I wrote about when I headed off to the UK in search of some Torontonian history back in 2014. You can read about the infamous horse manure here.

And that wasn’t the only tangential Toronto connection to Victoria’s coronation. A young soldier named John Henry Lefroy played a very small role in the proceedings that day, long before moving to our city to build a magnetic observatory and become the subject of one of the most valuable paintings in Canadian history. I wrote about that story here.

I’m Offering A New Walking Tour Next Weekend!

Spring is here! Which means it’s walking tour season again! I had a blast exploring the city with you last year, so I’ll be offering lots of historical walking tours again in 2023 — probably about one a month between now and December. To kick things off, I’m creating a brand new tour all about the history of the Toronto islands.

Our islands haven’t always been a peaceful place. They’ve witnessed many of the city’s most dramatic events — from deadly shipwrecks and heroic rescues to heart-breaking disaster and bone-chilling murder. We’ll meet on a Saturday afternoon to explore the hidden history of the islands on a walk from Hanlan’s to Gibraltar.

When: Saturday, May 13 at 4:15pm

Where: Meet at the Hanlan’s Point Ferry Deck — on the island. If you take the 4pm ferry to Hanlan’s Point, you’ll be there on time and we won’t leave without you! The tour will last about 1.5–2 hours and end at Gibraltar Point. Once we’re done, you can either retrace our steps to the ferry or continue on to enjoy the rest of the islands!

Price: Pay what you can

My New Online Course Begins Soon!

As I’m sure you’re painfully aware, people in Toronto are no strangers to the challenges of getting around. Those frustrations have a long history in our city, stretching all the way back to its founding and beyond. In my new four-week online course, we’ll dive into some of the most fascinating Toronto transportation tales — from shipwrecks and stagecoaches to traffic jams and train derailments. We’ll learn about the warships that once sailed the waters of Lake Ontario, the exciting summer when bicycles first arrived in our city, the portage trail that gave Toronto its name… and much, much more.

The course will kick off on May 17 and be held every Wednesday night at 8pm. If you have to miss any classes, don’t worry! All the lectures will be recorded so you can watch and re-watch them whenever you like. And if you’re a paid subscriber to The Toronto History Weekly, you’ll get 10% off!

This Monday Night — An Exclusive Online Soiree For Paid Subscribers!

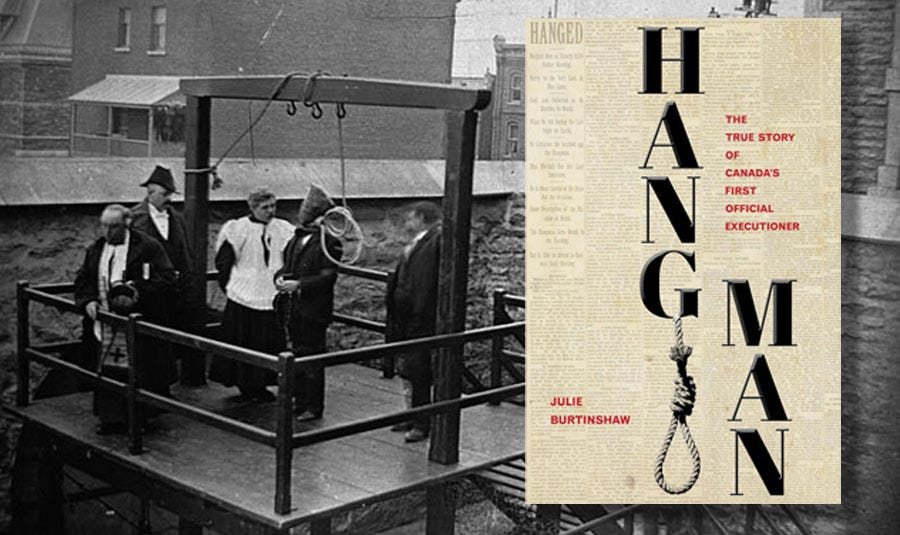

John Radclive has a gruesome place in Canadian history. In the late 1800s, he was hired to become our country’s first official executioner. He would spend decades in the role, killing scores of people. The photo above is from one of his hangings; thought to be the last public execution held in Canada. And now author Julie Burtinshaw has published a new book all about Radclive and his life: Hangman: The True Story of Canada’s First Official Executioner. Having shared a few grisly historical tales myself, I’ve been very excited to read it. And now I’m even more excited to get the chance to have a chat with the author over Zoom — and all of you paid subscribers are invited to join us!

I’ve been looking for some unique ways to thank those of who’ve been willing to support The Toronto History Weekly with a few dollars a month. It’s only thanks to you that the newsletter gets to continue! So if it goes well and we get a nice crowd, I’m hoping to organize more of this kind of event in the future.

The gruesome soiree will be held over Zoom at 8pm on the night of Monday, May 8. I’ll send out the link to all paid subscribers ahead of time. And it will be recorded, so anyone who has to miss it can watch it whenever they like.

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber and you’d like to make the switch, all you have to do is click the button below. Not only will you get invited to exclusive events like the one above, you’ll also be supporting all my work while helping to ensure The Toronto History Weekly survives. This newsletter is a ton of work! Only about 5% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 20 other people.

QUICK LINKS

I’ve already used up the entire Substack length limit thanks to the lengthy story of the Canadian arch, so I don’t have room for my usual round-up of local heritage news, but the Quick Links section will return next week!

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

MASS CAPTURE: CHINESE HEAD TAX AND THE MAKING OF NON-CITIZENS

May 8 — 7pm — Toronto Reference Library (Beeton Hall)

“Professor Lily Cho joins us to discuss her award-winning book, Mass Capture: Chinese Head Tax and the Making of Non-citizens. Through extensive archival research on C.I.9 certificates, Canada's first mass use of photo identification, the book delves deep into the history of surveillance and exclusion against Chinese migrants in the country.”

Free!

AFRICAN-CANADIANS IN THE U.S. CIVIL WAR: EXPLORED THROUGH HISTORY AND POETRY

May 12 — 6:30pm — North York Central Library (Auditorium)

“This year is the 160th anniversary of Black troops entering the Union Army. Join the Society and Recreation department for a discussion about African-Canadians and their journey crossing the border and their contributions in the war against slavery. No registration required.”

Free!

GOOD AND EVIL: THE TRUE STORY OF CANADA’S FIRST HANGMAN

May 15 — 7pm — Riverdale Library

“Author Julie Burtinshaw will present her biography of John Radclive, Hangman: The True Story of Canada's First Official Executioner. She will discuss the research and writing process, Radclive's personal and professional life and the questions the story raises about Canadian attitudes towards capital punishment.”

Free!

&

HANGMAN: THE TRUE STORY OF CANADA’S OFFICIAL EXECUTIONER

May 16 — 7pm — Queen/Salter Library

“Author Julie Burtinshaw will present her biography of John Radclive, Hangman: The True Story of Canada's First Official Executioner. She will discuss the research and writing process, Radclive's personal and professional life and the questions the story raises about Canadian attitudes towards capital punishment.”

Free!

As a Toronto-native, I'm SO thrilled to have found a Toronto-based history stack. Instant subscribe!