The Bloody Burlington Races & the War for Lake Ontario

Fighting the Americans on the water, plus Toronto's oldest bar, a talking pineapple, and more...

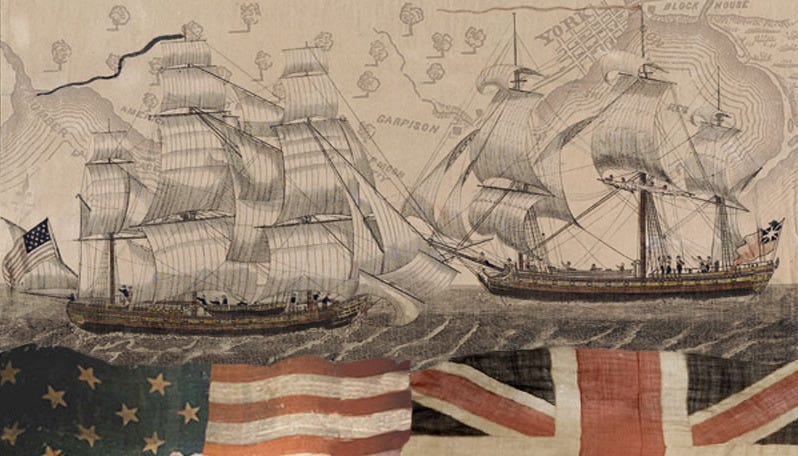

With my new course beginning on Monday — all about cross-border tensions between our city and the United States — this seems like a good time to share a chapter from The Toronto Book of Dead. One of the War of 1812’s big naval battles broke out in the waters off our shores just months after the Americans attacked our city during the Battle of York. On that day, they had hoped to capture a partially-built ship at the foot of Bay Street, HMS Sir Isaac Brock. A massive explosion at Fort York had killed their general and the British had burned the ship rather than allowing it to be taken. The Americans took revenge by occupying the town for the next six days, burning buildings, terrorizing the townspeople, finally leaving weighed down by all the loot they’d pillaged…

This time, they came at dawn. Just a few months after the Battle of York, as a black September night gave way to the light of day, the American fleet was spotted again, far out in the water south of Toronto. In April, they had come to capture one ship. Now, they wanted the entire British fleet.

York was in the middle of an arms race. The Great Lakes were one of the most vital battlegrounds in the War of 1812. Controlling the water meant you could move your troops and supplies wherever you wanted — while keeping the enemy from doing the same. That advantage might decide the fate of the entire war.

Both sides rushed to build the most powerful fleets possible. Some of the biggest warships in the world were being hammered together in the shipyards on either side of Lake Ontario. They had crews of hundreds of men; they bristled with dozens of guns. They turned the lake into the scene of countless horrors. When warships met in battle, the results were so gory that some crews spread sand across their decks to keep them from getting too slippery. Others painted them red so the blood would blend in.

HMS Sir Isaac Brock would have been the second-biggest ship on Lake Ontario if it had been completed. And even though the Americans had failed to capture it during the invasion of York, the burning of the vessel had been a terrible blow to British hopes. In the months after, the advantage on the Great Lakes swung dramatically toward the Americans. In early September, they won a stunning victory on Lake Erie. They captured the entire British fleet on that lake, giving them complete control of it. Now, they just needed Lake Ontario: “the key to the Great Lakes.” If they won it, they would be able to pull off their grand plan: ship troops down the St. Lawrence River and besiege Montreal.

So now the Americans sailed back toward Toronto, where the British fleet was waiting. This would be a bloody day, with the potential to change the entire course of the war.

The American in charge was Commodore Isaac Chauncey. He was from Connecticut, but had first made a name for himself fighting pirates off the coast of Tripoli. Back in April, he’d been in charge of the American ships invading Toronto. Now, he was commanding his fleet from the deck of a brand new flagship: the USS General Pike (named after the American general blown up at Fort York). The Pike sailed at the head of a squadron of ten ships, some towed behind the others for extra firepower. The Americans had bigger guns with longer range than their British counterparts. But their ships were also slower and harder to manoeuvre.

The British squadron was smaller: just six ships. It was commanded by Commodore Sir James Yeo, an Englishman who had been welcomed to Upper Canada as a hero — one of the rising stars of the most powerful navy on the planet. He sailed aboard his own brand new flagship, HMS General Wolfe (named after yet another dead general: the one who died fighting the French on the Plains of Abraham). The Wolfe was the sister ship of the burned Brock, and had been built in Kingston at the same time as the Brock had been under construction at York.

As dawn broke over Lake Ontario that morning, the Wolfe and the rest of the British fleet were just to the west of York — not far from Port Credit. When they spotted the Americans, they were still about a dozen kilometres away.

The battle got off to a slow start. With all that distance between the two squadrons, Commodore Yeo and his men had enough time to sail over to the harbour at Toronto, sending a small boat ashore with an update. Meanwhile, the Americans patiently stalked their prey: they sailed up to a spot south of the peninsula [now the islands] and waited.

It wasn’t until mid-morning that Yeo turned his squadron around and left York, sailing south out into the lake. The Americans followed, chasing the British with the wind in their sails. They were steadily gaining. It wouldn’t be long now. Both fleets shifted into single-file lines: battle formation.

It was Yeo and the British who made the first move. A little after noon, the Wolfe suddenly swung around, heading back toward the Americans, trying to run by the Pike and open fire on the middle of the enemy line.

Commodore Chauncey and the Americans countered. The Pike began to turn, too, trying to cut the Wolfe off, drawing closer and closer and closer... until there were only a few hundred metres between them. But until it had fully swung around, the Pike’s formidable bank of guns wouldn’t be pointing in the right direction. The American flagship was exposed.

The Wolfe opened fire. The British guns roared smoke and iron, cannonballs whizzing through the air between the two ships, smashing into the vulnerable Pike. One British volley after another tore into it.

Slowwwwwwly, the great bulk of the Pike continued to swing around. Now, the might of its broadside was finally facing the Wolfe. Fourteen American cannons burst to life: a wall of white smoke and fire.

Back and forth, the two great flagships thundered. Wood burst into splinters. Sails were ripped and torn. Blood spilled onto the decks. On board the Pike, a mast snapped, toppling into the sails below.

And then: catastrophe for the British. One of the masts on the Wolfe came crashing down, pulling a second mast, sails, rigging, and weights down with it — they tumbled onto the deck and then over the side into the water. Without them, the Wolfe was in serious trouble.

At that moment, it seemed as if everything was lost. The Pike was closing in, the American sailors were reloading their guns, the end was drawing near. “In the battle for control of Lake Ontario,” the historian Robert Malcomson wrote in his history of the campaign, “this instant may have been the most pivotal.” The Americans were about to win the day — and with it, the entire lake. The whole war might follow.

It was the Royal George that saved the day. It was the second ship in the British line — and it had finally turned around, too. It rushed into danger, sailing right into the line of fire, putting itself between the Americans and the wounded Wolfe and then opening fire. Again and again and again, the Royal George’s guns roared, sending a hail of iron death flying into the Pike, buying enough time for the rest of the fleet to join the fight. Ships on both sides fired volley after volley, smashing into wood and skin and bone. All was smoke and chaos.

On board the Wolfe, the British crew rushed to recover. They dumped their dead overboard, carried the wounded below deck, cut away at the tangle of debris. And they did it all quickly. Fewer than fifteen minutes after the Wolfe’s masts tumbled into the water, the ship was ready to go.

But the danger wasn’t over yet. Without a full complement of sails, the Wolfe was still vulnerable. The fate of Lake Ontario still hung in the balance. So Commodore Yeo turned his flagship around, let the wind fill what was left of the tattered sails, and raced west as fast as he could go. The rest of the British fleet turned and followed. They headed straight for the end of the lake, toward Burlington Bay, toward safety.

It was a decisive moment for Commodore Chauncey and the Americans. Two of the British ships were momentarily exposed — they could be captured. The master commandant of the Pike, Arthur Sinclair — great-grandfather of the American writer Upton Sinclair — begged the commodore to forget about the Wolfe and take the other ships instead. Capturing even one or two of the British vessels would be a major victory.

But Chauncey had a bigger prize in mind. Immortality was within his grasp; he could taste it. This was the day he was going to defeat the entire British fleet on Lake Ontario. He wasn’t going to be distracted. “All or none!” he cried, ordering his fleet to sail west, to chase down the British squadron and defeat them.

The race was on.

For the next hour and a half, all sixteen ships sailed west as fast as they could, speeding across the water south of where Oakville is today.

As the afternoon wore on, a storm gathered. The sky darkened. The waves got bigger. The wind was picking up, blowing in hard from the east, filling the sails of the ships, pushing them ever faster as they raced toward the western end of the lake.

From shore — not just along the Canadian beaches, but also far over on the American side — people strained to follow the movements of the distant ships as they jockeyed for position. Some joked that it was like watching a yacht race. That’s how the battle got its name: the Burlington Races.

The Wolfe was in rough shape, but the ship was still fast. So was the rest of the British fleet. The Americans struggled to keep up. It was only the Pike that managed to stay close enough to keep the British within the range of its guns. They echoed out across the lake, blasting away at the British vessels. But the Pike was badly wounded, too. Masts were damaged. Sails were torn. Rigging was cut to pieces. Some of the guns were completely useless. And the ship was leaking: the hull had been hit beneath the waves; there was water coming in below deck. The American sailors scrambled to pump it out as fast as it was coming in.

“This,” Master Commandant Sinclair later remembered, “was the most trying time I ever had in my life.”

Then, suddenly, the most deadly moment of the entire battle: one of the big guns near the front of the Pike exploded. The deck was torn apart in an instant. Iron shards flew in all directions, slicing through wood, sails, and flesh. The deadly debris was flung all the way back to the stern of the ship. More than twenty American sailors were killed or wounded in the blast.

Still, the injured Pike and the rest of the American fleet sailed on, chasing the British fleet, cannons roaring. But try as they might, the Americans weren’t catching up. They were running out of time. There wasn’t much lake left. They were getting closer and closer to Burlington Bay, closer to shore, closer to safety for the British ships.

There are two different stories about what happened next.

The most recent evidence seems to suggest that Commodore Yeo picked a spot to make a stand. He had the British fleet drop anchor near shore — just to the east of Burlington Bay (which we call Hamilton Harbour today). Bunched together with their backs protected by the land, they presented a daunting target. Their cannons were ready. On shore, there were even more friendly guns nearby.

With the British in such a strong defensive position and the Pike already badly damaged — maybe even in danger of sinking — Commodore Chauncey realized it was all over. If he fought on, he risked beaching his ships in enemy territory. He’d missed his chance. The American fleet turned and sailed away into the storm.

But that’s not the story we’ve been told for most of the last two hundred years. In the most famous version of the tale, Commodore Yeo and the British fleet kept sailing straight for Burlington Bay. If they did, it was a daring move. The waters at the mouth of the harbour were shallow; the Wolfe would be in danger of running aground, stranded and helpless as the Americans swooped in. But at the very last moment, riding the crest of the storm surge, they say the Wolfe swept into the bay and to safety. The Americans had no choice but to turn away.

That fabled moment has been immortalized in paintings and textbooks; it was even printed on the historical plaque that stood overlooking the bay until it was updated just a few years ago.

Either way, the British fleet survived.

That night, anchored safely inside the harbour, the tired sailors got to work. In the cold, wind, and rain, they rushed to repair the Wolfe and the other battered ships as quickly as possible. The injured men were treated for their wounds. The dead — those who hadn’t already been tossed overboard — were sewn inside their hammocks and buried at sea. The work continued all through the next day and into the following night. One man climbing the mast of the Wolfe lost his footing and tumbled to his death. And still the crews worked: it would be another two days before the fleet was ready to return to the lake.

Of course, there were more terrible, bloody days to come. Thousands of people died on both sides of the war. Others returned home wounded, many deeply scarred by the things they had seen and done. Just a week after the Burlington Races, Tecumseh — famed leader of the First Nations confederacy — was killed in battle against the Americans. That same day, Commodore Chauncey and his American fleet captured five British ships far on the other side of Lake Ontario. They burned a sixth.

But winter was coming. The sailing season was soon over. The British fleet had survived another year and the Americans still didn’t control Lake Ontario. Without free reign on the water, their invasion down the St. Lawrence ended in humiliating defeat.

The very next summer, shipbuilders in Kingston built a new warship, one that changed everything. It took more than five thousand oak trees, two hundred men, and nearly ten months to make HMS St. Lawrence. It was by far the biggest thing that had ever sailed on the Great Lakes, boasting more than a hundred guns and a crew of seven hundred. It was bigger even than the flagship Admiral Nelson had used to beat Napoleon’s navy at Trafalgar. The St. Lawrence was so big and so powerful that the ship’s guns never had to fire a single shot. The Americans immediately gave up trying to conquer Lake Ontario. Commodore Chauncey and his fleet were stuck at home for the rest of the war.

It didn’t last much longer. At the end of 1814, the peace treaty was signed. The War of 1812 was finally over. The American invasion of Canada had failed.

You can learn more about The Toronto Book of the Dead here. It’s available from all the usual places, including your favourite local bookstore (like Queen Books or the Spacing Store) or directly from my publisher at that link.

Toronto vs The United States: A History of Cross-Border Tensions (My New Online Course!)

With threatening news making headlines just about every day right now, I’m feeling more than a little unsettled. So I thought I’d follow up my History of Hope & Resistance in Toronto with another online course created in response to today’s events, devoted to the long, long history of tensions between Canada and the United States…

Course Description: Toronto hasn’t always gotten along with our neighbours to the south. Originally founded as a home for refugees from the American War of Independence, our city was created in direct contrast to the United States. And in the centuries since, cross-border tensions have deeply shaped our history.

Generations of Torontonians have stood strong against invasion and threats of annexation while working hard to make our city a safe haven for those fleeing hardships south of the border. In this online course, we'll explore those stories in four weekly lectures — from the War of 1812 to the Underground Railroad to the draft dodgers who refused to fight in Vietnam. Faced with our own unsettling times, we'll take a look back at the Torontonians who have lived through frightening eras before us — and how, in the process, they made our city into the place it is today.

When: The course begins at 8pm on March 24 and runs every Monday night for four weeks.

Where: Over Zoom. All lectures will also be recorded, so if you have to miss any of them you can watch them whenever you like. The recordings will remain available for the foreseeable future.

Cost: Pay what you like!

Secrets of the PATH — A New Walking Tour

There are strange tales hidden beneath our city, found in the most unlikely places. The PATH is filled with them: from pirates and curses to dead whales and mysterious disappearances. So, we’ll spend an afternoon searching for those bizarre histories in the nooks and crannies of our subterranean mall. And we’ll be joined by a special guest: Toronto Star reporter Katie Daubs, who once spent two weeks living in the PATH!

When: Sunday, March 23 at 3pm.

Where: Meet inside the Eaton Centre — outside Treehouse Toys (near Queen Subway Station). The tour will last about 2 hours and end not far from the intersection of Bay & Queen’s Quay.

Price: Pay what you like!

Thank you so much to everyone who has made the switch to a paid subscription! It’s only because of the heroic 4% of readers who support the newsletter with a few dollars a month that The Toronto Time Traveller is able to survive. If you’d like to make the switch yourself, you can do that right here:

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything new in Toronto’s past…

FINAL NEW BIOGRAPHIES NEWS — The Dictionary of Canadian Biography has published the final pair of Natasha Henry-Dixon’s new entries about people who were enslaved in Upper Canada.

She wraps up the series by writing about John Baker. He arrived in the town of York (now Toronto) in 1795, was freed when the man who enslaved him drowned in a shipwreck, joined the miltiary, fought against the American invaders during the War of 1812 and Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, and by the time he passed away in 1871 it was thought he might have been the last surviving person to have been enslaved in our province. Read more.

The other one of the final entries is about George Martin. He was the son of Peter Martin — the subject of another one of the biographies and witness to Chloe Cooley’s resistance as she was sold across the Niagara River. Peter was eventually able to buy George’s freedom, and the son would also go on to fight against the Americans during the War of 1812 before spending the final years of his life in poverty. Read more.

DRUNKEN DESIGNATION NEWS — Toronto’s new Chief Planner, Jason Throne, shares the news on Bluesky that our city’s oldest bar, the Wheatsheaf, was approved for heritage designation by the Planning & Housing Committee. Which is something I am definitely surprised it didn’t already have! View on Bluesky.

BROCKTON MAP NEWS — Eric Sehr continues his project about the history of Brockton Village by mapping Black families in the west end in the 1860s. Read more.

ANANAS NEWS — For Defining Moments, Jamie Bradburn takes a look back at the history of teaching French via television, from talkign pineapples to separatist hobo clowns. Read more.

TRAILER PARK NEWS — At Spacing, Ian Darragh shares a fascinating story from the current City of Toronto Archives exhibit “If These Walls Could Talk: Researching the History of Where You Live”: the trailer park that used to stand on University Avenue (where Sick Kids is now) and how City Council tried to shut it down. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

REMEMBERING RAP CITY: THE LEGACY OF CANADIAN HIP HOP TELEVISION

March 22 — 1pm — Art Gallery of Ontario

“On the occasion of its 35th anniversary, Roots Rhymes Collective (RRC) and the AGO celebrate the legacy of MuchMusic’s ground-breaking and innovative hip hop television program, RapCity. Launched in September 1989, RapCity has been credited with platforming Canadian hip hop talent from coast to coast, as well projecting what has been dubbed the ‘Canadian Hip Hop Nation’ to international audiences outside of Canada’s borders. Join us for a discussion with some of RapCity’s creators and legendary personalities as we celebrate RapCity’s contributions to the history of Canadian and global hip hop landscapes. Conversations will reflect on RapCity’s early days, its power as platform for hip hop culture and its practitioners, and its challenges and triumphs as the show took its place in Canadian television history.”

$15 for members of public; $13 for annual passholders; $10 for members.

NEWSGIRLS: GUTSY PIONEERS IN CANADA’S NEWSROOM

March 25 — 2pm — Mount Pleasant Library

“Toronto author, freelance writer and former Toronto Star reporter, Donna Jean Mackinnon, documents the lives of 10 leading female reporters who started their careers during newspaper's Golden Age. MacKinnon's fascinating, often amusing, presentation includes a slew of vintage photos and intimate anecdotes. Trailblazers in their fields, these adventurous 'newshens', as they were once called, covered every beat from art openings, fashion, crime, politics to major social issues of the day.”

Free with registration!

OUT FROM THE SHADOWS: WOMEN AND THEIR WORK IN 19th CENTURY TORONTO

March 25 — 2pm — Morningside Library

“Author Elizabeth Gillian Muir discusses her book, An Unrecognized Contribution: Women and their Work in 19th-century Toronto, which details the work that women did in the city that has not been recognized in early histories. While women did own factories, taverns, pubs, stores, market gardens, butcher shops, brickyards, and other commercial ventures, their contributions to these industries have been hidden for decades. The presentation will include photos and time for a Q & A.”

Free!

WHEELING THROUGH TORONTO: A HISTORY OF THE BICYCLE AND ITS RIDERS

March 25 — 6:30pm — Yorkville Library

“Cities around the world, including Toronto, are embracing the bicycle as a response to the climate crisis. This is not the first time the bicycle has come to our rescue, proving itself a loyal friend during times of crisis, including the world wars and the COVID pandemic. In ‘Wheeling through Toronto, A History of the Bicycle and Its Riders’, author Albert Koehl takes the audience on a 130-year ride through the rich history of the bicycle in Toronto. By understanding how we got here, we can begin mapping a way forward, one in which the potential of cycling is maximized.”

Free!

IF THESE WALLS COULD TALK — RESEARCHING THE HISTORY OF WHERE YOU LIVE

Until March 27 — Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm — City of Toronto Archives

“Every home has a story to tell. No matter the location or the income or origin of its residents, there are stories to be discovered in the traces buildings leave behind in the archival record. This new exhibit from the Toronto Archives explores the unique stories of 11 homes from across Toronto, ranging from a Georgian house in the downtown core to a strip mall in the inner suburbs. Each property features a variety of archival resources used to plot key points on its timeline – the building blocks used to assemble the home’s history. As you’ll discover, you don’t need to be an archivist or a historian to do this kind of research. Your starting point is an address and your own curiosity.”

Free!

UNSOLVED CRIMES: MYSTIFYING MURDERS AND BAFFLING CASES

March 27 — 6:30pm — Toronto Reference Library

“Interested in true crime? Toronto Reference Library is hosting a monthly True Crime Series of panel discussions with some of Canada's top crime writers. This month panelists: Kevin Donovan offers insights about the high-profile Sherman case based on his Toronto Star reporting and his book, The Billionaire Murders: The Mysterious Deaths of Barry and Honey Sherman. Robert Hoshowsky discuss several Toronto-based cases from his book, Unsolved: True Canadian Cold Cases. Moderator: Nate Hendley, renowned and award-winning author of The Beatle Bandit and other true-crime books.”

Free!

Great issue Adam!