Today is Simcoe Day in Toronto. So I thought it would be a good time to share the story of the man who our August long weekend is named after — and of his strange and complicated relationship to slavery, since he was an avowed abolitionist who once fought a war to preserve it.

John Graves Simcoe was the founder of Toronto. He was a British soldier who’d made his name fighting against the American revolutionaries during the War of Independence. In the wake of that war, the British created a new colony as a home for American refugees — those who’d stayed loyal to the crown and were no longer welcome in the new United States. The British called their new colony Upper Canada (what’s now known as southern Ontario). And they picked Simcoe to run it.

By then, Simcoe had already made it very clear that he was an abolitionist. Back home in England as a member of parliament, he gave anti-slavery speeches in the House of Commons. And when he was chosen to become the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, he declared that he saw no place for the practice in his new colony. “The principles of the British Constitution,” he wrote, “do not admit of that slavery which Christianity condemns. The moment I assume the Government of Upper Canada, under no modification will I assent to a law that discriminates by dishonest policy between natives of Africa, America or Europe.”

And indeed, one of the very first things Simcoe did when he got to Upper Canada was to pass a law against slavery.

His direct inspiration came from the story of Chloe Cooley. She was a Black woman enslaved at Niagara who had long carried out acts of resistance: refusing work, disappearing for period of time, stealing things, generally making her enslavement as inconvenient as possible for the man who enslaved her. And during Simcoe's first winter in Upper Canada, that man “sold” her to someone on the American side of the border, tying her up with rope and forcing her into a boat to be carried across the river. She resisted yet again, screaming and putting up a fight.

Peter Martin saw it all happen. He was a Black soldier, a Loyalist who'd fought on the British side of the war. A week later, when Simcoe’s Executive Council met for the first time, Martin appeared before them to tell them the tale.

Simcoe saw his chance. He used Cooley's story as an opportunity to push for abolition in Upper Canada. In July 1793, the “Act Against Slavery” became the very first law against slavery ever passed anywhere in the British Empire. And so, to this day, Simcoe is celebrated as the man who ended slavery in our province — more than 40 years before it was abolished across the British Empire and 70 years before the Emancipation Proclamation in the United States.

But things weren’t quite as simple as that makes it seem.

For one thing, Simcoe’s law wasn’t as groundbreaking as it sounds. By the time he came to Canada, slavery had already effectively been ended inside England by a court decision fifteen years earlier. So by that standard, the Canadian colonies were actually behind the times. Hundreds of people were enslaved in Upper Canada, many of them brought north to the new province by those Loyalist refugees who fled the United States. The British government had encouraged the practice, promising new Canadian settlers they could bring the people they enslaved with them.

So, while slavery inside England had already ended, if Simcoe wanted to get rid of slavery in Upper Canada he would need to pass a new law actively abolishing it. And that wouldn’t be easy.

Simcoe would need support. The bill would have to pass through the Legislative Assembly and then through the Legislative Council. Both of those bodies were full of slaveholders. And that was thanks, in part, to none other than John Graves Simcoe.

The Legislative Assembly was an elected body. But the members of the Legislative Council were hand-picked by Simcoe himself — it worked a bit like the Senate does today. And Simcoe had packed his Council full of slaveholders. At least five of the nine members were either slaveholders themselves or from slaveholding families. They formed a majority. Simcoe, determined to abolish slavery in Upper Canada, had made it almost impossible to do.

So, he was forced into a compromise — the exact thing he had promised never to do. “The Act Against Slavery” law didn’t abolish it immediately; instead, it would be gradually phased out. People who were enslaved could no longer be brought into Upper Canada, but anyone who was already here could be enslaved for the rest of their lives. Their children would be born into slavery, too; they wouldn’t be free until they turned twenty-five. Finally, anyone who wanted to free someone they enslaved was discouraged from doing so: they would be forced to provide financial security to ensure the newly freed resident wouldn’t be a drain on the resources of the state.

The bill was passed just a few weeks before Simcoe founded Toronto. And so, the foundations of our city were laid, in part, by slave labour. During the early years of the new town, there were fifteen Black people enslaved within its borders — and another ten just across the Don Valley.

Some of Toronto’s slaveholders are still familiar names today. The Jarvis family is remembered by Jarvis Street. James Baby’s old estate on the Humber River is still called Baby Point. The Denisons gave their name to Denison Avenue and Denison Square. Peter Russell — a gambing addict ex-con who Simcoe put in charge of many of the colony’s financial matters — enslaved a woman named Peggy Pompadour and her three children: Jupiter, Amy and Milly. He brutally punished them for their acts of resistance: Jupiter was once bound and strung up in the window of a storehouse as a painful public humiliation. Russell is still remembered in the names of Peter Street and Russell Hill Road.

And that was just the beginning of Simcoe’s strange relationship to slavery. It only got more complicated after he left Toronto. In 1796, ill-health forced him to sail home to England. And just a few months later — while still officially serving as Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada — Simcoe was sent to Haiti. There, the avowed abolitionist was asked to put down the biggest uprising against slavery since Spartacus.

Haiti was a French colony back then; they called it Saint Domingue. The leaders of the French Revolution had abolished slavery, but French royalists still controlled Haiti, where half a million people were enslaved.

When those people rose up in a revolution led by François Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture, the French royalists asked the British for help. Thousands of British troops were sent to the island, hoping to crush the uprising, restore slavery, and secure the island’s sugar riches for themselves. By the time Simcoe arrived, they’d been fighting for years without making any real progress. His job was to turn things around. He was appointed as commander of the British forces in Haiti — a man who hated slavery fighting a bloody war to preserve it.

The Haitian Revolution was a long and brutal struggle. It raged for thirteen years and claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. Countless atrocities were committed. Simcoe’s attempt to keep his own men in check — an order to halt all “cruelties and outrages” — was ignored. His army pushed Toussaint’s forces back, but were stalled by a counterattack. His men were dying by the thousands: some in battle, still more of yellow fever.

Simcoe only lasted a few months before he seems to have gotten tired of fighting for a cause he didn’t believe in. He was sick of the war, sick of a lack of support from his superiors, sick of literally being sick. He left Haiti and sailed home to England, where he tried to convince the government to withdraw from the war; he was nearly arrested for desertion. He spent his most of his remaining years helping to lead the battle against Napoleon.

The British kept fighting in Haiti for a year after Simcoe left, and the French kept fighting long after that. In the end, the Haitian Revolution was successful — it led to the establishment of a new, independent, slavery-free country in 1804.

But while slavery was now over in Haiti, it was still part of life in Toronto. The numbers of people enslaved here gradually decreased, but it was decades before slavery was finally and fully abolished in Upper Canada — and across the rest of the British Empire, too — on August 1, 1834.

So Simcoe Day isn’t the only holiday we commemorate today. It’s Emancipation Day, too.

By the time slavery was abolished here, Toronto was already beginning to gain a very different reputation. Black families like the Abbotts, the Blackburns and the Augustas worked with white allies like George Brown to make Toronto a more welcoming place, struggling to turn it into a relatively safe haven for those fleeing slavery in the United States. They organized anti-slavery societies, secured housing for new arrivals, and raised funds to help them get started in their new city.

Half a century after Simcoe’s chilling compromise, Toronto had become an important stop at the end of the Underground Railroad. And that story became the one Torontonians like to tell ourselves. But Simcoe Day and Emancipation Day provide us with a reminder that there are other stories, too. Stories too often forgotten or ignored. Stories of those who were enslaved here — and of the complicated truth behind Simcoe's famous law.

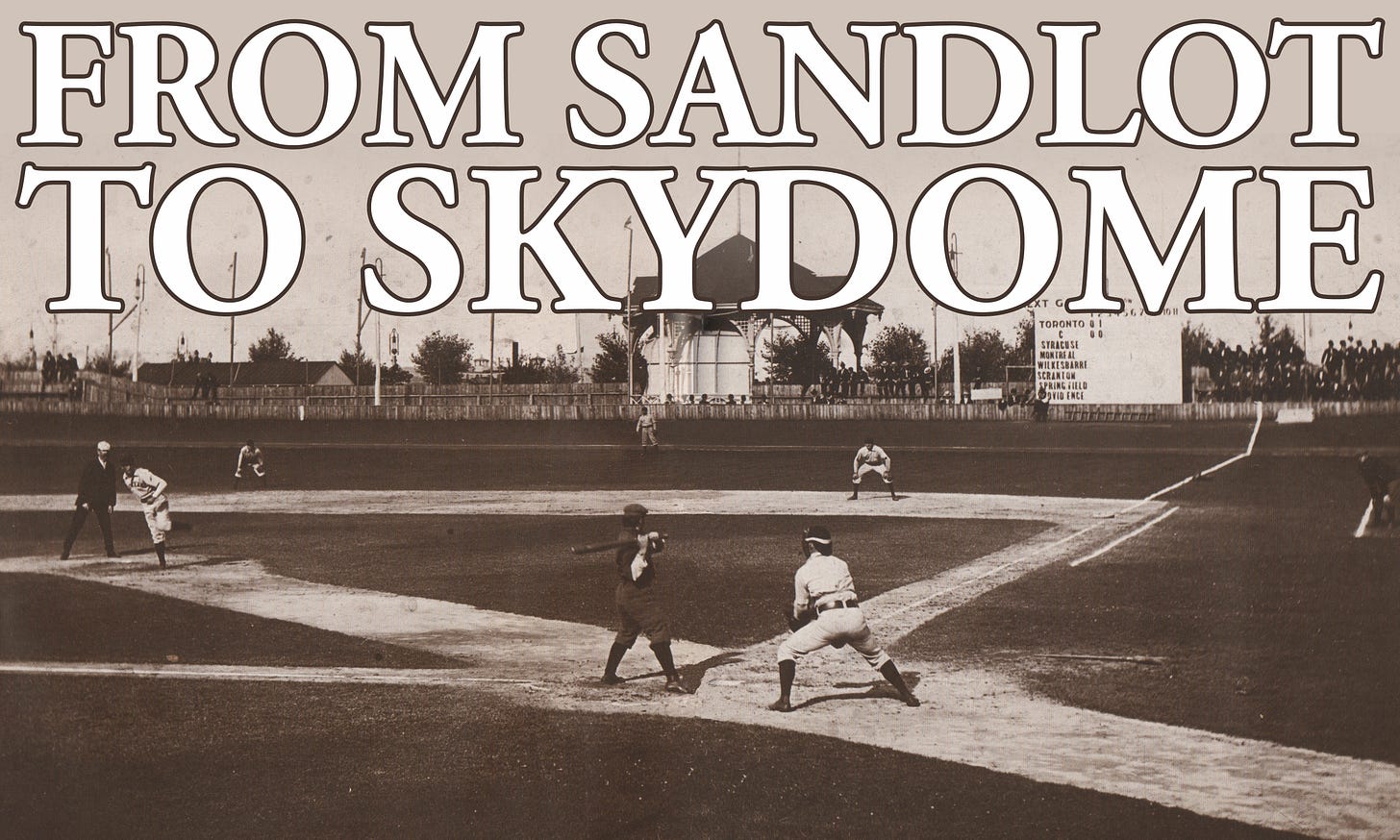

EXPLORING TORONTO’S BASEBALL HISTORY

My Toronto baseball history course is back! It was a big hit when I first offered it last year, and a few of you have been asking when it would return, so I’ve resurrected it for another go!

Baseball was being played in Toronto more than a century before the Blue Jays were born. So over the course of four lectures, we'll explore the game's evolution in our city — from the days when it was a working class sport played by "undesirables" to Joe Carter jumping for joy in front of 50,000 screaming fans. Along the way, we'll meet everyone from con artists and kidnappers and polygamists to feminist icons — the people who've made Toronto baseball what it is… and helped transform our city in the process.

The course will be held online over Zoom — and even if you can’t make all the dates, don’t worry! All the lectures will be recorded and posted to a private YouTube page so you can watch them whenever you like.

Paid susbscribers to this newsletter will also get 10% off the course as a thank you for your support! The Toronto History Weekly will only survive if enough of you make the switch, so I’m incredibly grateful to all of you who do. And you can do it by clicking right here:

A FREE TALK ABOUT TORONTO’S STRANGEST RIOT

This year’s Toronto History Lecture is being held on Wednesday — and I’m giving it! It’s 100% free to attend, all over Zoom, so if you’re looking for something to do that evening, I hope you’ll join us! Here are all the details…

THE TORONTO CIRCUS RIOT: A TRUE TALE OF SEX, VIOLENCE, CORRUPTION AND CLOWNS

August 3 — 7:30pm — Online — Toronto Branch, Ontario Genealogical Society

The strangest riot in our city’s history broke out in the summer of 1855. It was sparked by a brawl at a King Street brothel, when some rowdy clowns picked a fight with a battle-hardened crew of firefighters on the most dangerous night of the year. The bizarre encounter would reverberate through the city that night and into the following day. The circus performers had made a terrible mistake; those firefighters were members of the Orange Order, the powerful Protestant society that ruled Toronto for more than a century. And they wanted revenge. The circus grounds would soon become the scene of a bloody clash that shook Toronto to its core and laid bare the fault lines that violently divided our city.

Free with registration!

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

WASAGA BEACH WAR NEWS — The Beanery Gang was one of Toronto’s most notorious gangs in the late 1940s. Lorna Poplak wrote about them for TVO this week, including their vicious battle with another Toronto gang at Wasaga Beach, “breaking bones and leaving trails of blood behind.” Read more.

TRANSIT TIMEWARP NEWS — Trevor Parkins-Sciberras is, in his words, “obsessed with transit history.” And so, he puts together then-and-now photo comparisons of Toronto’s transit past, and shares them in his “Transit Timewarp: Toronto & Beyond” Facebook group. Briony Smith interview him for The Toronto Star this week. Read more.

EATON’S NANNY NEWS — Peggy Fitzgerald grew up in Ireland during the Great Depression, but eventually found herself living in Toronto and serving as a nanny of one of the wealthiest and most powerful families in Canada: the Eatons. Tracy Wong takes a look at her life in The Toronto Star. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

DIS/MANTLE EVENING: MRS. PIPKIN’S MANOR

August 5 & 6 — 6pm — Spadina House

“Louisa Pipkin was a freedom seeker, who escaped enslavement in the United States and came to Canada where she worked as a laundress in the 1870s for the Austin family, the founders of the Dominion Bank of Canada and the homeowners of Spadina. Dis/Mantle is inspired by the real Mrs. Pipkin and the efforts of Black abolitionists. … This evening is a reimagining of Spadina Museum utilizing an Afrofuturistic narrative where Mrs. Pipkin is the homeowner and the house is a haven for those who travelled safely to southern Ontario via the Underground Railroad. It is an immersive experience using portraiture, decorative arts, performance and sound to bring forth the under-represented history of Black people in Toronto and is inspired by the efforts of Black abolitionists.”

Free with registration!

SUMMER HISTORY SERIES: ETOBICOKE’S HISTORIC LAKESHORE

August 18 — 7:30pm — Online — Etobicoke Historical Society

“Mimico, New Toronto and Long Branch share many things, including the streetcars of Lakeshore Boulevard West and the beautiful shores of Lake Ontario, but they have very different histories. Mimico is an older town, once the home of palatial estates. New Toronto had its start as a gritty industrial suburb. And Long Branch began as a gated, upper class cottage community and resort in Victorian times. Join EHS Historian Richard Jordan as he travels back in time on this virtual historic tour of Etobicoke’s three lakeshore communities.”

Free!

WALKING TOUR — 1813: TERROR IN THE TOWN OF YORK

August 18 — 7pm — Meet at Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Explore the Town of York on foot with one of our expert historians! In this walking tour, join us as we explore the Battle of York while we walk the original 10 blocks of the early city. Tours start and end at Toronto’s First Post Office. Tours run rain or shine, and may cover rough ground, so please dress accordingly. All ages are welcome. Dogs and bicycles are welcome as we walk, though portions of some tours may include indoor areas where they are restricted.”

$16.93 for non-members; $11.62 for members.

RAILWAY TECHNOLOGY IN THE CANADIAN FIRST WORLD WAR EFFORT

August 18 — 7pm — Online — Toronto Railway Museum

“Explore the complexities of transportation and logistics in the forward areas of the Western Front during the First World War. Join us and presenter Andrew Iarocci on Thursday, August 18 at 7:00 PM (EST) for a free online lecture. Learn about how railway technologies and expertise were gradually integrated into the British (and Canadian) transportation system, in an effort to streamline and rationalize the movement of ammunition, supplies, and personnel.”

Free with registration!

NEIGHBOURHOOD TOUR: HUNGRY FOR COMFORT

August 20 & 21 — Various times — Mackenzie House

“Mackenzie House’s Hungry for Comfort Neighbourhood Tour explores the influence of the Black community on food culture in Toronto from the 1830s- 1860s. From grocers, to caterers, to purveyors of fine dining, each of the individuals included represents a different aspect of foodways. The walking tour begins at the Northeast corner of King & Church Streets and ends at Mackenzie House with a tasting of Trinidadian snacks by Pelau Catering.”

Free with registration!

WALKING TOUR — ON THE EDGE OF THE CITY: TORONTO IN 1833

August 27 — 10:30am respectively — Meet at Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Imagine a Toronto where the tallest building is only three stories high, where Lake Ontario reaches Front Street, where the wagon wheels grind through the muddy roads, the air smells of smoke and animal, and the surrounding lands is farms, fields, and forests. This was what the neighbourhood looked like in the early 1800s. In this walking tour, explore the surviving built environment of the original 10 blocks of Toronto and discover how the Town of York, which started as a colonial outpost with a couple hundred residents, became the City of Toronto in 1834, with a population of just under 10,000.”

$16.93 for non-members; $11.62 for members.