Michael Snow's Venice Dream

Plus: From Hogtown To Downtown is back, an American highway on Canadian soil, and more...

If you live in Toronto, you know Michael Snow’s work — even if you don’t know his name. He’s the artist who created Flight Stop (the Canada geese who soar through the air inside the Eaton Centre), The Audience (the giant bronzed baseball fans peering down at the city like gargoyles from the side of the SkyDome) and Lightline (the strip of purple light that runs up and down a downtown skyscraper). But when Snow died this week at the age of 94, the legacy he left behind was about far more than just adorning public buildings. “Michael Snow was undoubtedly the most influential postwar Canadian artist,” the Power Plant gallery’s Adelina Vlas told The Globe. “One can hardly imagine the history of Canadian contemporary visual arts without his work.” And not only did Snow help transform the Canadian art world, he changed our country and our city with it.

Snow was born in Toronto at the end of the 1920s, a city that was still considered to be a notoriously conservative and boring place. But even as a kid growing up in the sheltered streets of Rosedale, he still managed to find his way to the most thrilling influences of the age. He fell in love with jazz music, spending long hours listening to the likes of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton, formed a band and smoked pot with his fellow musicians, argued about clarinets until the sun came up. He gigged as a pianist as a young man, playing jazz clubs at night while dedicating his days to his other passion: art.

He studied at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD) at a deeply exciting time, influenced by the generation of groundbreaking modernist rebels who’d recently revolutionized art — from Pablo Picasso’s audacious cubism to Marcel Duchamp’s satirically provocative urinal. And it wasn’t long before Snow began to make a name for himself in the local art scene, ruffling some feathers himself in the process.

He was just 26 when he and another artist opened an exhibition of their work at Hart House. It proved to be so controversial, the mayor stepped in. Nathan Phillips demanded that three nudes be taken down off the walls while criticizing Snow for calling his painting of a woman holding a rooster, Woman With Cock In Her Hand.

By the time he turned 30, Snow had already been given his first solo show at the city’s most promising new art gallery. (Avrom Isaacs’ gallery would also help launch the careers of William Kurelek, Snow’s soon-to-be wife Joyce Wieland, and many others). And he’d been hired by George Dunning, the future of director of Yellow Submarine, who sparked his interest in film. Soon, Snow would gain a reputation as a daring multimedia artist, breaking down barriers between painting, film, sculpture, and sound. When the country’s gaze turned to Montreal for Expo 67, Snow’s Walking Woman motif was the centrepiece of the Ontario pavilion.

His impact extended far beyond the borders of our own country, too. His experimental film, Wavelength, isn’t for the faint of heart — it’s a single, 45-minute zoom shot in which very little happens — but it’s also been repeatedly listed as one of the greatest and most influential films of all-time. Snow was the first Canadian to have a solo show at MOMA, and his work has been displayed in galleries all over the world.

Still, there were few bigger honours than the one that came in 1970. Snow was chosen to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale — the world’s oldest international art festival. The list of those who’ve been chosen to display their work inside the elegant Canadian pavilion includes some of the biggest names in our country’s artistic history: Emily Carr, Alex Coville, Sorel Etrog, Frances Loring, Stanley Douglas, General Idea… But Snow was the first Canadian to be chosen alone, invited to Italy as a single artist rather than being presented in a group, his photographs and sound installations taking a central place upon one of the art world’s most prestigious stages.

It was a big enough deal that the CBC sent a film crew to Venice for the occasion. They arrived in time for the opening of his show and were still there the next day, following along as Snow headed out into the city to create a new work.

Venetian Blind is a series of selfies taken decades before that term was coined. Snow photographs himself in front of famous Venetian landmarks. But instead of giving the audience a view of one of the world’s most beautiful cities, he obstructs it. The frame of each photo is largely filled by the artist’s own blurry face, his eyes closed shut so that not even he is taking in the sights. He’s blinded, the audience is blinded, the camera is blinded, and in a way he’s even playing the role of a blind himself, obscuring the view of Venice like the slats of a venetian blind might obscure the view out a window, thus completing the title’s pun.

Snow had been interested in blindness since he was a kid. His father had been caught in an explosion while working in a tunnel as an engineer. One of his dad’s eyes was blinded instantly; the other was filled with dust that gradually eroded what was left of his vision. Venetian Blind is one of Snow’s most dramatic explorations of that theme. But it also resonates beyond it.

Snow’s visit to Venice came at an unsettling moment in history. The Sixties had just ended and the Seventies were already off to a rough start. “The tragic spring of the Kent State killings and the invasion of Cambodia were not easy memories to erase,” the CBC explained over footage of a Biennale gala. The Cold War was very much at its height and Snow admitted it weighed on his mind and influenced his work. “I often think that the end of the world, or the end of human life on earth, is fairly near. And so obviously, one should do something to attempt to prevent that. Believe it or not, I think that an artist should continue to produce art towards that end.”

According to Snow, simply leading the life of an artist was a vitally important act. “I think the artist’s life is exemplary,” he explained with a chuckle. “It’s perfectly obvious that in the last five years what kids have really been involved in is taking things from the bohemian tradition.” An easy claim to make during the days of hippies, pot smoke and peace protests. “A lot of things have risen to the surface that have been part of [the] artist’s lifestyle for many, many years and they now are more and more popularly accepted.”

And while he worried it was a lost cause, he believed an artistic approach offered a more promising path forward for the world. “What is needed as a goal is a new kind of attitude to what is important in life… Personally, I feel I have experienced living in that way, with that kind of attitude, a little better than [most] — and I think a lot of artists have, too.”

Venice was the perfect setting for those thoughts. The beautifully decaying city has been inspiring artists for centuries, a place where it’s easy to contemplate the end of things. “Venice is a museum,” Snow told the CBC, “a relic of a great past… Basically what you’re in is a frame.” And that frame provides an opportunity.

Watching the CBC’s footage of Snow creating Venetian Blind can be a touching and inspiring experience. Here’s a Canadian artist at the height of his powers, the day after the opening bash for his show at one of the world’s most distinguished events, wandering around one of the most beautiful cities on the planet with a simple polaroid camera, making a strange and silly and serious little art piece that will still be talked about half a century later, collaborating with his wife and fellow artist Joyce Wieland, knowing he’s failing to get the effect he wants each time he closes his eyes, shakes his head into a blur and snaps a pic, attracting small groups of confused passersby who stop to watch what he’s doing, a TV crew trailing along and asking him questions as he stands surrounded by a crumbling metropolis that is quite literally sinking beneath his feet, all of it a quiet act of hope and defiance in the face of a world so hellbent on hate and exploitation that it threatens to end itself, an artist reminding us that in some ways the act of making art is even more important than the art itself.

Maybe I’m just being overly romantic and naive, but I don’t know… It means something to me. And in it, I recognize an approach I’ve tried to adopt in some of my own work.

I started writing about the history of Toronto back in 2010, with a strange little art project of my own. The Toronto Dreams Project is a series of postcards, each one featuring a short story I’ve written about a figure from our city’s past — a fictional dream I imagine they might have had. I place the dream cards in public places connected to that person’s true history, leaving them for strangers to find… a hook, I hope, to pique people’s curiosity about the city’s past.

Just before the pandemic hit, I took Michael Snow’s example. I headed to Venice in the autumn of 2019 as part of The Toronto Dreams Project’s Grand Tour of Europe, leaving dreams about figures from Toronto’s past in foreign cities connected to their lives. I created a dream for Michael Snow ahead of that trip, leaving copies in places where he exhibited his work: outside the Pompidou Centre in Paris; on La Rambla in Barcelona; at the Canadian Pavilion of the Venice Biennale.

The day after visiting the Biennale (that year’s Canadian representative was the Inuit art collective Isuma), I rushed around the city recreating Venetian Blind. It was a deeply silly act; I knew I was being ridiculous as I squeezed my eyes shut on one bridge after another, collecting odd glances from tourists and locals as they passed by. But it was also a strangely enlightening experience. You can’t help but ponder the implications of Snow’s original piece as you close your eyes to take a photo of yourself obscuring a view of the Rialto Bridge or the Grand Canal. And to think about the meaning Venetian Blind has in our current age, the way it foreshadowed ideas about selfie culture — how in a lot of ways artistic approaches to life have indeed become more widespread, as Snow hoped, but have also been swallowed up by capitalism and turned everyone’s lives into products to be consumed on their own social media feeds. Not to mention what it has to say about modern, selfie-driven tourism and the impact its had on Venice — the urge to see the city before it disappears (and to be seen in it) helping to speed up the city’s destruction. At the same time, as I always do when I’m exploring the history of a place, I felt strongly connected to the past — and to Michael Snow, recreating in some small and ridiculous way the experience he’d had in Venice half a century earlier.

Of course, I’m far from the only one who’s been inspired by him. Snow grew up in a Toronto that was notoriously boring, repressed and repressive. The fact our city is now a more vibrant, artistic and exciting place (though it still has a way to go, of course) is in part thanks to his work — as well as those who’ve been inspired to follow in his footsteps.

The Globe’s obituary quotes an old magazine profile that declares Snow “single-handedly transformed Toronto from a Group of Seven-worshipping, landscape-loving hayseed backwater into a hub of high-stakes, high-concept art.” And his influence isn’t limited to the confines of galleries or art history lectures. His major public pieces, like Flight Stop and The Audience, have become so familiar to us in the decades since they were installed that they almost blend into the background. But the simple fact they exist makes our city a little easier to fall in love with, to care about, to cherish and work hard to improve — even in the face of austerity-driven decay. And the fact Michael Snow lived the life he did, not just the life of an artist, but the life of a successful Canadian artist makes it easier for others to imagine such a thing is possible.

It’s no coincidence that one of the most beloved cultural institutions to come out of one of Toronto’s most optimistic eras — the early-2000s Torontopia era of David Miller, Spacing and Trampoline Hall — took its name from Snow’s most famous film. The Wavelength music series is where acts like Broken Social Scene, Peaches and The Hidden Cameras got their start. And we’ll never known how many others have been inspired, in ways great and small, directly and indirectly, by the work Snow produced over the course of a 70-year career. Nor will we ever know how many more will be inspired in years to come, even now that he’s gone.

He might have been an avant-garde artist celebrated by art snobs, aficionados and collectors, but in many ways we’re all living in Michael Snow’s Toronto.

WATCH THE CBC’S REPORT FROM VENICE

READ THE GLOBE & MAIL’S OBITUARY FOR MICHAEL SNOW

—

I’ll share the dream I wrote for Michael Snow below. But I’ve also been very busy already this year, so I’ll quickly share a couple of other bits of news first…

FROM HOGTOWN TO DOWNTOWN IS BACK!

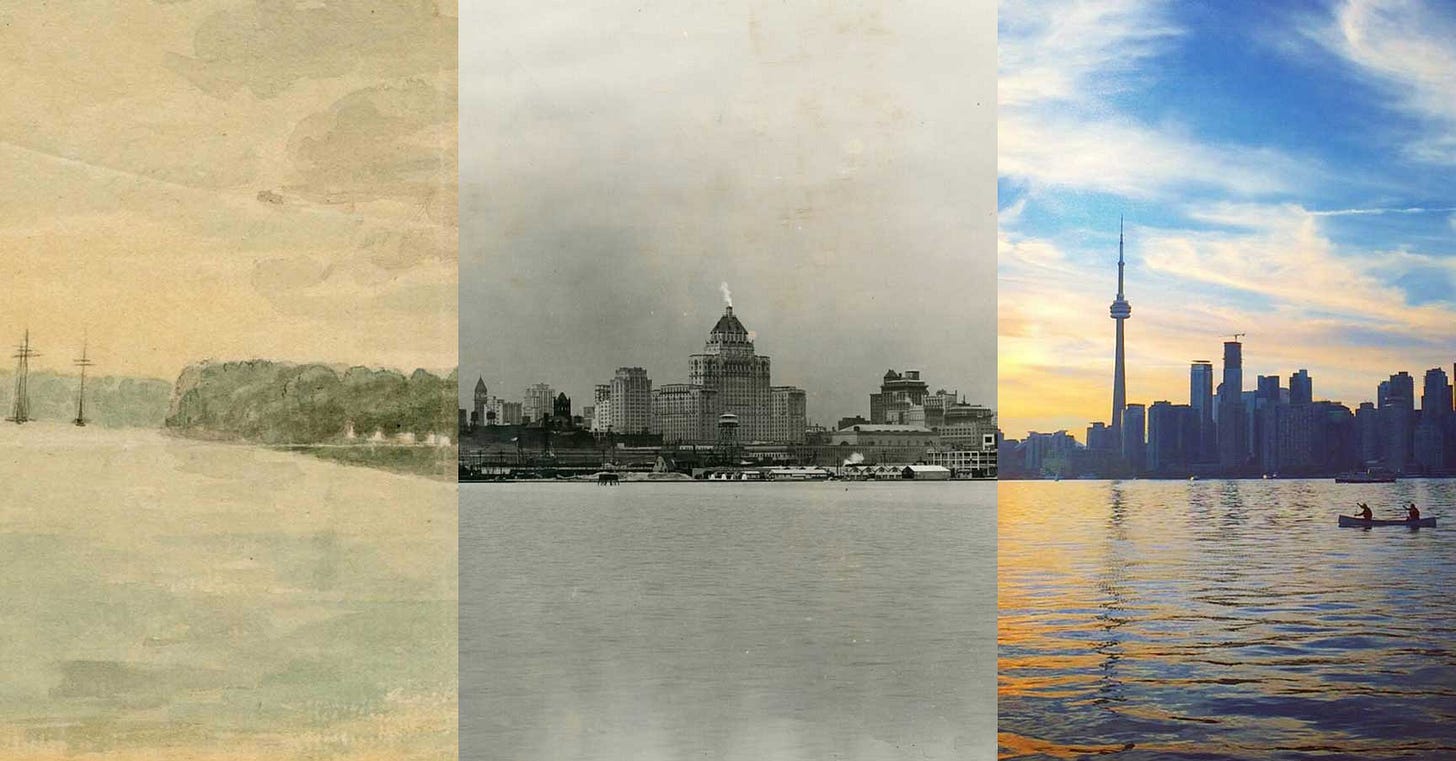

I’m kicking off 2023 by bringing back the biggest and most popular of all my Toronto history courses. From Hogtown To Downtown: The History of Toronto in 10 Weeks is an overview of the whole history of the city in ten weekly lectures. Here’s the course description:

The history of Toronto is filled with fascinating stories that teach us about ourselves and our community. In this ten-week online course, we'll explore the city's past from a time long before it was founded, through its days as a rowdy frontier town, and all the way to the sprawling megacity we know today. How did Toronto become the multicultural metropolis of the twenty-first century? The answer involves everything from duels to broken hearts to pigeons.

It will kick off on the night of Sunday, January 22. And if you’re interested but concerned you might have to miss some classes, don’t worry — all the lectures will be recorded and posted to a private YouTube playlist so you can watch them whenever you like.

It should be a fun way to spent some Sunday nights during the coldest time of the year. Hope some of you can join us!

If you’d like to get 10% off the course — or just want to support The Toronto History Weekly and ensure it can keep going — you can to switch to a paid subscription by clicking the button below. Only about 5% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 20 other people, as well as support all the work I do in sharing stories from our city’s past:

THE AMERICAN HIGHWAY BUILT ON CANADIAN SOIL — AND HOW IT HELPED WIN THE WAR

This is one of my favourite photos of me — in fact, it’s the one I use as the main image on my website. I’m standing at Soldier’s Summit in the Yukon’s Kluane National Park. This is the place where the Alaska Highway was officially opened.

It’s one of the most spectacular roads in Canada, running for more than 2,000 kilometres, from northern B.C. through the Yukon and then across the border into Alaska. It’s also one of the most fascanting roads in the country, with a bizarre and unlikely origin story. This Canadian highway wasn’t built by Canadians. It was built by the American military, created to defend against the Japanese Empire and assist the Soviet Union in its fight against Germany.

My collaborator, Ashley Brook, snapped this photo while we were in the Yukon filming a new episode of our Canadiana documentary series — a short video all about the highway and its remkable history.

The episode was released this week — and as always, you can watch it free on YouTube:

THE TORONTO DREAMS PROJECT: “THE ELECTRIC SLEEP” (MICHAEL SNOW, 2002)

The artist dreamed Yonge and Dundas Square was filled with beds. They stretched out row after row, an expanse of pillows and polka dot sheets. Members of the public — shoppers, tourists, passersby — were invited to lie down on the cots. To close their eyes surrounded by skyscrapers and billboards. To drift off. To sleep.

Each bed was outfitted with a headset: a strange metallic bowl brimming with wires. These bizarre scientific contraptions could read your thoughts as you slept; they could detect and document your dreams. And those wires, snaking their way across the pavement toward the edges of the square, were plugged directly into the flickering video billboards that loomed overhead.

So, as the people of Toronto slept below, their dreams and nightmares were broadcast in brilliant LED colour. The billboards lit up with people flying through the clouds. Falling from cliffs. Running scared from the monsters of their minds. And as they did, crowds gathered to watch, laughing and applauding, waiting for their chance to lie down and plug in.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE TORONTO DREAMS PROJECT

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

CITY HISTORY AT ITS VERY BEST NEWS — There was more sad news in the world of Toronto history over the holidays. Sarah Gibson was the author of several books about local history, including Inside Toronto: Urban Interiors 1880s to 1920s which sits on my own bookshelf. It was none other than Jane Jacobs who called Gibson’s debut, More Than An Island: A History of the Toronto Island, “city history at its very best.” Read more.

DIS/MANTLE — The Dis/Mantle exhibit at Spadina House (which I’ve mentioned a few times before) didn’t close as planned on New Year’s Eve… which is wonderful news for me because I’ve somehow still not made it out to see it. It reimagines the history of the house, centering it around the story of Louisa Pipkin (a Black woman who worked there as servant to the wealth Austin family). It’s been extended to May 28, and just in time for Steve Paikin to write about it for TVO. Read more.

DRUNKEN CHRIMSTAS NEWS — Jamie Bradburn looks back at Christmas in Ontario 100 years ago. One of my favourite tidbits? “At Toronto’s police court, sentences of 10 days in jail for drunkenness if offenders couldn’t pay the $10 fine were reduced on Boxing Day to five days to, according to the Toronto Daily Star, “enable the crowd of tipplers to start the new year afresh.” Read more.

NEW YEAR’S EVE ATTACK NEWS — And he also shares a post from his archives, about a hateful attack on the TTC on New Year’s Eve 1967. “Carson, who had fought in the Second World War and Korean War and worked as a counsellor at the Don Jail, told the Star that he had “never seen hate in the eyes of men as I did on the subway train that night.” Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

DAVID A. ROBERTSON: RECONILIATION, REPRESENTATION, AND THE POWER OF TRUTH

January 12 — 7pm — Lilian H. Smith Library

“An acclaimed author, David A. Robertson is now also the editorial director of a new children's imprint at Penguin Random House, dedicated to publishing works by Indigenous writers and illustrators. His lecture concerns the disastrous effects of misrepresentations of Indigenous peoples in popular culture, both on their self-perceptions and on the perceptions of non-Indigenous people. While depictions of Indigenous peoples have improved in recent years, there is still work to be done. What are the impacts of this negative representation on all segments of the population, both historically and from a contemporary perspective? How can accurate representations, particularly through own-voice literature, change this country within the context of reconciliation?”

Free!

CURATOR’S TALK: LEONARD COHEN: EVERYBODY KNOWS

January 20 — 6pm — AGO

“Join exhibition curator and the AGO’s Deputy Director and Chief Curator, Julian Cox for a talk describing his research and exploring the themes of Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, a landmark exhibition dedicated to the life and times of iconic Canadian artist Leonard Cohen.”

$10, or $5 for members

LIVING IN INTERESTING TIMES: TWO LOYALIST

January 23 — 7:30pm — Both online & at Lansing United Church — Toronto Branch of the Ontario Genealogical Society

“While building out his family tree, Rick Hill was surprised to discover a 3rd great-grandmother who could have boasted that three of her four grandparents were United Empire Loyalists—and she had a Loyalist great-grandfather, too! During the American Revolutionary War, these UEL ancestors—Henry Dennis, his son John, John’s wife Martha (née Brown), and Lawrence Johnson—all fled Pennsylvania. Three of the four made it out of the future USA, first to Nova Scotia, and ultimately to York Township and the Town of York in Upper Canada. Their stories include the Battle of St. Lucia, the Quaker religion, losing a husband at sea, founding a settlement that banned slave masters, shipbuilding in Kingston, ill-starred actions in the War of 1812, a house at the corner of King & Yonge, a Methodist bishop, and the first customer of a new burial ground.”

Free, I believe!

Holocaust Remembrance Day Recollections: Renate Krakauer

January 25 — 12pm — Online — Toronto Public Library

“While Holocaust Remembrance Day commemorates the murder of six million Jews by the Nazis, it also reminds us what can happen when an evil regime takes power with little or no opposition. Explore the history of the Holocaust and the attitudes and social forces that enabled one of the darkest periods of human history to occur. Meet Holocaust survivor, Renate Krakauer, and listen to her testimony, ask questions, and gain a better understanding of the impact of the Holocaust at a personal level. Introduction provided by Daniella Lurion from Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center for Holocaust Studies (FSWC).”

Free!

THE LEGACY OF THE SLAVE TRADE IN CANADA

February 2 — 7pm — Gerrard/Ashdale Library

& Feburary 15 — 12:30pm — City Hall Library

“Author Andrew Hunter presents a reading and conversation about his new book "It Was Dark There All The Time: Sophia Burhen and the Legacy of Slavery in Canada". Joining the author will be Karen Harkins (Toronto Culture Division), Adrienne Shadd (author; "The Underground Railroad: Next Stop, Toronto!") and Charmaine Lurch (artist/educator) as they discuss the book and provide an examination and reflection on the history of chattel slavery and its legacy of racism in Canada.”

Free! Registration is encouraged for the February 15 event.