Heartbreak on Humber Bay — A Deadly Night for the Junction

Plus weird island history, my chat with The Toronto Star, and more...

It was a dark and stormy night. July 1907. A police officer was patrolling the shores of Humber Bay, walking along the lakefront at Sunnyside, when he heard sounds floating to him across the water. It was late, long after midnight, and the weather was miserable — it had been raining on and off for hours. But someone was still out there on the bay. It sounded like a group of young men, singing and having fun, loud enough to be heard over the rattling hum of their boat engine.

But now, the weather was beginning to worsen. The wind was suddenly picking up, big menacing gusts, and the rain began to fall in torrents. As the officer peered out into the darkness, trying to spot the men, their singing turned into cries of panic. Terror. The officer called out to them, trying to make some contact across the growing waves, but there was no response. Something had gone wrong, but there was nothing he could do stranded on the shore by himself. There was no emergency equipment nearby. No lifeboat. No radio. Nothing.

He rushed off for help. But by the time it arrived, it would be far too late.

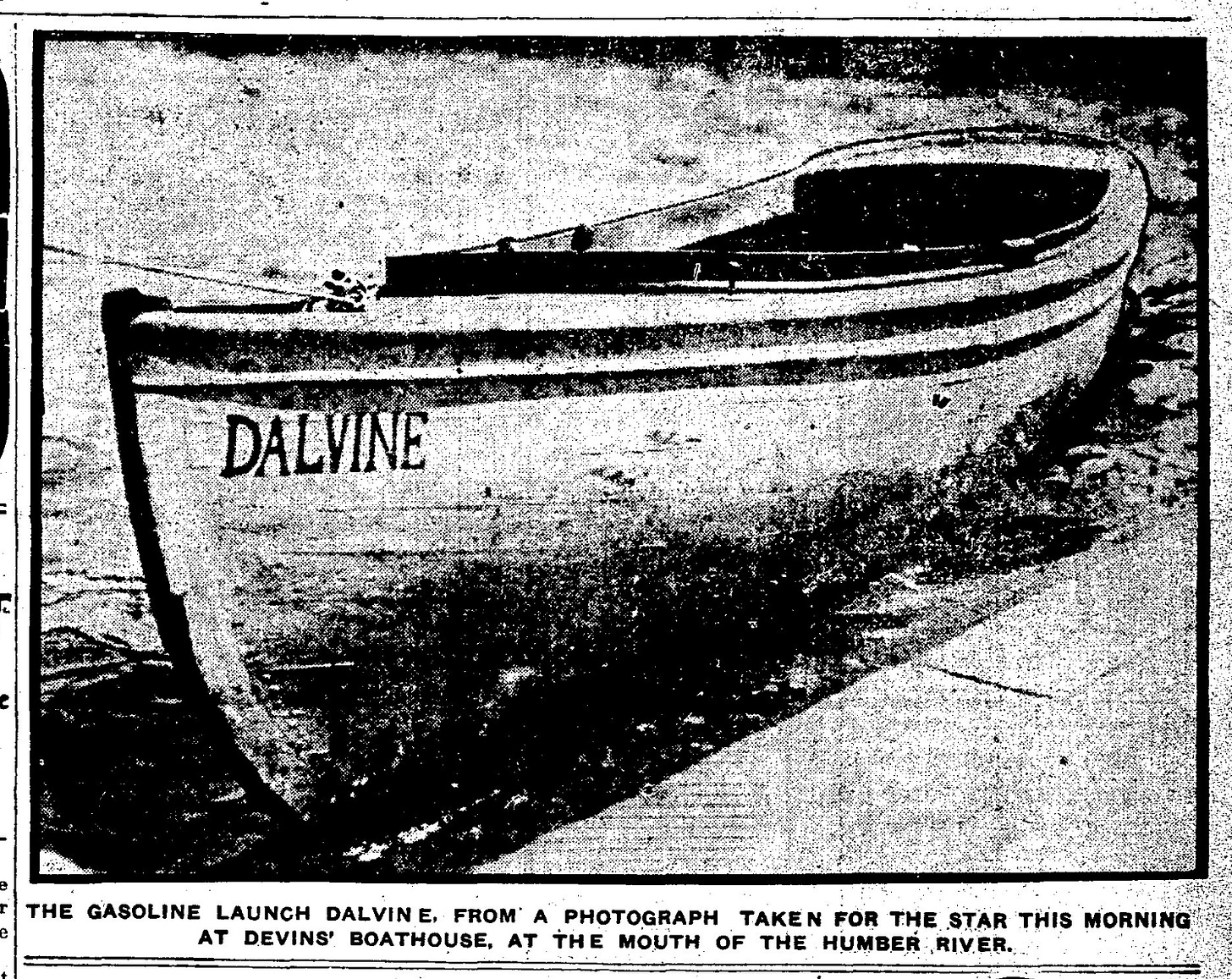

There were ten young men out there in the storm, each about nineteen or twenty years old. They were all from the Junction; it was still its own town back then, a little west of Toronto. Most of them worked on the railroads that gave the community its name. Just a few weeks earlier, a couple of them had bought their own little boat. They called it the Dalvine — a combination of their last names: Daly and Irvine — and strapped a motor to the back. It was a loud and unreliable thing. "It was a cranky engine," according to The Toronto Star, "and again and again it had caused laughter at the Humber by its noisy workings, and frequent balkings." But the boys were proud of it. That group of friends had spent as much as time as possible out on the water that month — including that fateful summer night.

They set out around ten o'clock, leaving the Humber River to sputter their way across Humber Bay, bound for the island. They came ashore at Hanlan's Point an hour later, where the big attractions were already shut down for the night. The amusement park sat dark, the baseball stadium empty, the hotel quiet. But the Junction boys made their own fun. They took shelter from the rain under the roof of a big pavilion. One of them had a harmonica; he started playing as the others sang along. A couple of them even danced a waltz. And as the downpour continued deep into the night, they lay down to get some rest until the weather passed, falling asleep to the sound of the falling rain.

It wasn’t until after midnight that they were roused from their slumber. A night watchman and a police officer came by to let them know the rain had stopped and it was clear to go home. And so, the ten young men piled back into the Dalvine and set out toward home. They got off to a bit of an uneasy start — the engine briefly stalled, and the officer called out to them with a friendly warning to sit down so they wouldn't tip over — but they were soon on their way, singing and laughing as they went.

It wasn't until they reached Humber Bay, out in the water south of High Park, that things began to go wrong. The lake had been calm when they left the island, but now the weather was turning — and it was turning quickly. The waves were picking up. And as they did, the boat began rocking back and forth dangerously. An inquest would later find the Dalvine was poorly built, without a wide enough hull, not designed to ply the wild waters of our lake. One expert claimed, "You couldn't get a better design for a rocker for a cradle." As the boat was tossed about in the waves, some of the boys grew worried; they couldn't swim.

That's when the engine died. The Dalvine was now at the mercy of Lake Ontario. The boat was battered by the waves; they crashed into it broadside, relentless, overwhelming. Within seconds, the Dalvine had tipped over, fully capsized. All ten men were thrown into the choppy water.

George Shields was one of them. He found himself fully submerged beneath the boat, fighting his way back to the surface. As he got his head above the water, he could see some of the others being tossed about in the waves. "Hang to the boat!" one of them cried. And so, Shields did. "I hung on the back of the launch for all I was worth," he later remembered.

Four of the other boys managed to do the same. But the lake wouldn't ease up; it kept pounding away, throwing the Dalvine back and forth. Shields' memory would be hazy, so the details are a bit unclear, but it seems that they eventually managed to keep the boat steady enough to crawl up on top of it. They sat on the keel for a while, but it was slippery and unstable and the waves kept coming. One boy fell off; another swam after him and pulled him back. But as the minutes ticked by, it would get harder and harder to keep touch with the boat.

They called out for help, but when the police officer at Sunnyside called back from the shore, they couldn't hear him over the sound of the storm. There were other people nearby who heard their cries, too, but assumed they were just horsing around. "So many people yell on the bay," one explained, "and some of them even yell for help when they do not need it."

No one would come to their rescue. And so, one by one, over the course of the next half hour, the young men lost their grip, slid off into the water, and were gone. Eventually, Shields was the only one left clinging to the side of the boat.

"The next thing I remember is striking the sand of the shore," he told the inquest. "I lay there for a while." He was exhausted, soaked through, his chest cut and bruised. He wasn't sure what had happened to the others. He couldn't see much in the pitch black night. He assumed his friends had all swum ashore. He thought it was odd they hadn't waited for him, but figured they'd all gone home.

After resting there on the beach for a while, recovering, he headed home himself. He made the long walk through High Park before finally reaching the Junction. It was four in the morning by the time he stumbled in through the door of his family's home. He was so tired he could barely speak; he mumbled something about his friends having drowned, and then feel into a deep sleep.

The next day would prove to be one of the most sombre days in entire history of the Junction.

As the sun rose above Humber Bay, the police found the first of the bodies. It was Walter Dundin. He was half buried in the sand, sprawled out in the shadow of a willow tree not far from where the Dalvine lay washed up on the beach. His body wouldn't be the last body found that day.

At first, it wasn't clear who had lived and who had died. Even Shields still believed at least some of his friends must have made it ashore. Rumours ran rampant. "Like all tidings of grief and disaster," The Star reported, "the news of the catastrophe spread like wildfire… [It] flew from lip to lip and before noon the entire town knew it. People poured out into the streets and stood around discussing the calamity. Railroad men asleep after a night's work were awakened and told of the news… When the extra edition from the city arrived, the newsboys were besieged. They simply handed out the papers and took anything in the line of money they were offered."

As the rumours spread and the evidence began to mount, heartbreaking scenes of worry and grief were played out in homes across the Junction.

Two of the young men were brothers: Leonard and Frank Daly. The Star found their mother with tears streaming down her cheeks, neighbours trying in vain to comfort her. "Oh my boys, my boys!" she cried. "I know they're lost!" Gordon Laroque's mother lay weeping on a sofa in her kitchen, still trying to convince herself her son would come home safe. Joseph Irwin's father, fearing the worst, was heading to the morgue. Reginald Miller's brother rushed down to the waterfront, where people had begun to gather by the thousands. They watched with grisly curiosity as the authorities began dragging the lake. At least two more bodies were found that afternoon, both floating in the water. It would take all weekend before the last of the dead was recovered.

By then, the terrible truth was painfully clear. Nine of the ten Junction boys who had headed out onto the lake that night never came home. George Shields was the sole survivor.

The people of the Junction were no strangers to loss. But it had never hit them quite like this. As one resident explained to The Star, "Toronto Junction people are used to railway accidents — we have had quite a few of them — but this is a new and greater form of disaster than any railway wreck in the history of the town."

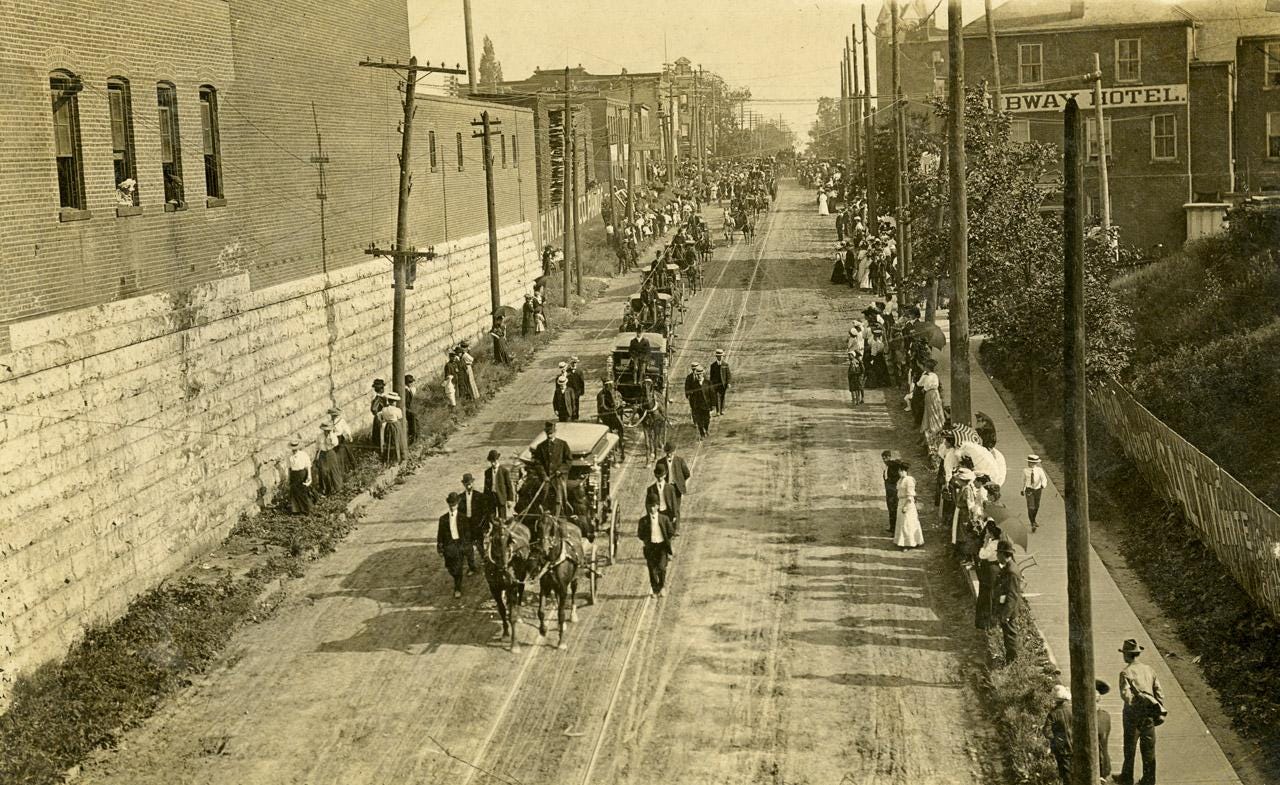

And so, the funeral that followed three days later wasn't just for the families of the dead, but for the entire community.

"Toronto Junction is a veritable house of mourning this afternoon," The Star reported. "Public buildings, stores, offices and houses are draped with the sable emblems of sorrow. People go about the streets with bowed heads and whispering voices. Over the whole town there seems to hang a pall of death and the poignant grief that only the hand of death can bring in to the human heart is everywhere evident." Factories fell silent. Shops were closed. The sidewalks were filled with mourners.

That afternoon, hundreds of people gathered at Victoria Presbyterian Church. The big red brick and limestone building stood in the heart of the Junction, on Annette just west of Keele. Six of the dead would be laid to rest nearby. The church was draped in black. The first few rows were filled with the grieving families. The grey caskets were alive with colour; each of them overflowed with flowers donated by the community.

After the service, the coffins were loaded into horse-drawn hearses. As the solemn procession made its way up Keele Street, bound for Prospect Cemetery, thousands of people stood silent witness along the side of the road. "The route of the procession is lined with a solid black wall of humanity," The Star reported. "The whole town has turned out to pay its last tribute to the memory of the bright young men who were cut off in the morning of their promising lives."

That town wouldn't be a town for much longer. Just two years after the deadly night on Humber Bay, the Junction was annexed by Toronto, swallowed up by the growing metropolis. It became one neighbourhood among many. In time, the memory of the nine men who died that summer began to fade. The city was full of tragedy, of heartbreak, of death.

But as you walk through the Junction today, there are still reminders. The trains still roll by, just as they did when those young men worked in the railyards. The church where their funeral was held is still there, too, turned into the Victoria Lofts. Many of the boys' homes have been demolished, but the house where George Shields lived, where he collapsed into sleep after his ordeal, is still standing on Heintzman Street today. It's a lovely building, blue with a little tree out front. More than a century has passed since the lake claimed those nine lives, but if you know where to look there are still echoes of that tragic night — and of the day the people of the Junction came together to mourn the terrible loss.

I’m In The Toronto Star Today!

I had a great time this week chatting with Doug Brod of The Toronto Star about The Festival of Bizarre Toronto History, along with some other strange stories from the city’s past. And then I got to head to the Distillery for a photoshoot with R.J Johnston. The results were published in today’s print edition of The Star. And you’ll find the story online, too:

Henry Box Brown & The Festival of Bizarre Toronto History

The Festival of Bizarre Toronto History is just a couple of weeks away and the line-up is quickly coming together! This week, I get to announce another one of the festival’s events.

This story might be a little familiar to long-time readers of the newsletter. It’s an extraordinary tale I wrote about a few months back. We’ll be spending an evening diving into the story of Henry Box Brown…

The Man Who Mailed Himself Out Of Slavery

The story of Henry Box Brown is one of the most incredible tales in North American history — and it has a deep Toronto connection. Brown spent the final years of his life living in our city. On the festival's third night, we'll talk about his dramatic escape from slavery, his eclectic theatrical performances, and Toronto's own history of racism on the stage with two renowned professors.

Dr. Cheryl Thompson is an Associate Professor in the Performance program at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is currently working on her third book about Canada's history of blackface as performance and anti-Black racism. Her previous books include Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture.

Dr. Martha J. Cutter is Professor of English and Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut, and the author of The Many Resurrections of Henry Box Brown (which you can get for 30% off by using the code "Cutter30" at that link) and "Will the Real Henry 'Box' Brown Please Stand Up?"

Wednesday, May 8 at 8pm — held over Zoom

GET YOUR FESTIVAL TICKETS HERE

Even if you can’t attend the festival, you can still support my work. The Toronto History Weekly needs your help! The number of paid subscriptions is verrrry slowwwwly creeping up, but since this newsletter involves a ton of work every week, it’s only by growing the number of paid subscriptions that I’ll be able to continue doing it. Thank you so, so much to everyone who already has — and if you’d to make the switch yourself, you can do it by clicking right here:

The Weird History of Our Islands

It was 166 years ago this month that the Toronto islands became islands. Before that, they were a sandy peninsula attached to the mainland. So, for my Weird Toronto History radio appearance this week, I thought I would share some of the strange stories that have played out on the other side of our bay — from the storm that created the eastern gap to the diving horses that once wowed crowds at the Hanlan’s Point Amusement Park.

Weird Toronto History airs every Tuesday afternoon at 3:20pm on Newstalk 1010.

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

BOVINE BAR NEWS — A few weeks ago, I mentioned that our city’s oldest bar was closing. The Black Bull originally opened on Queen Street in the 1830s. Two centuries later it’s still so beloved that when they announced they were closing, the crowds that showed up to say goodbye were so big they ran out of beer on the first night and were forced to shut their doors even earlier than anticipated. The bar’s future was unclear at the time, but now we know the building has been bought by the Score Pub Group, owners of the Score On King. So it looks like it will soon be a sports bar. Read more.

ARTS & CRAFTS NEWS — A strange one from earlier this month. A couple who own a 188-year-old home near Yonge & St. Clair have been trying to get the building’s heritage status removed by arguing that it shouldn’t be protected because the original owner was racist. City staff have reported that the heritage designation has little to do with that old resident. “Instead, the report says the home is worth preserving because it was designed by prominent Toronto architect Eden Smith and because of the unique structural qualities he brought to the building.” Read more.

SCORCHING HOT NEWS — The Great Fire of 1904 ravaged the downtown core 120 years ago this weekend. But it wasn’t our city’s first big blaze. For TVO, Jamie Bradburn takes a look back at the Great Fire of 1849. Read more.

RED ROCKET NEWS — …and that’s not Jamie’s only new piece. He also wrote an article about the opening of Toronto’s first subway… Read more.

JAMIE, I HOPE YOU GOT SOME REST AFTER ALL OF THIS NEWS — …annnnnd the origins of Regent Park, “Canada’s oldest social-housing project.” Read more.

STRAY CATTLE NEWS — Bob Georgiou takes a deep dive into the history of a fascinating little plot of land in the Canary District, which was home to the city’s pound back in the middle of the 1800s. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

ONTARIO CARNEGIE LIBRARIES

April 24 — 7pm — Northern District Library — North Toronto Historical Society

“Join Fiona Smith, Local History Librarian at the Toronto Reference Library, for a visual tour of Ontario's Carnegie Libraries through vintage postcards and other ephemera held in the Special Collections Department. The presentation will feature unique materials highlighting the history of Toronto's beautiful Carnegie branches.”

Free, I believe! (Annual memberships are $7.)

NEW DISCOVERIES DOWN BY THE BAY AT THE ASHBRIDGE ESTATE

April 24 — 7pm — The Beaches Sandbox — The Beach and East Toronto Historical Society

The Beach and East Toronto Historical Society in partnership with the Beaches Sandbox present Dena Doroszenko, senior archaeologist with the Ontario Heritage Trust, for a talk about new discoveries made down by the bay at the Ashbridge Estate.

Free!

THE TORONTO PREMIERE OF “ANY OTHER WAY: THE JACKIE SHANE STORY”

April 27 (9pm) & April 28 (8:45pm) — The TIFF Lightbox — Hot Docs

“Once you’ve heard Jackie Shane sing, you’ll never forget it. Yet, after shattering barriers as one of pop music’s first Black trans performers, this trail-blazing icon vanished from the spotlight at the height of her fame. From modest beginnings in Nashville, Shane soon recognized her talents and, in her late teens, made her way to Boston and Montreal, working the nightclub circuit while taking the stage with Frank Motley, a musician known for playing two trumpets at once. Her arrival in Toronto during its 1960s music explosion made her a highly sought-after headlining act who seemed destined to take her place among the R&B stars of the era. Blending her music with never-released phone conversations and soulful animated re-enactments, Any Other Way: The Jackie Shane Story brings Shane back to life in her own words, finally providing the recognition she so rightly deserves and introducing her to a generation fighting for their right to be their true selves.”

$17.70

BATTLE OF YORK DAY AT FORT YORK

April 27 — 11am to 4pm — Fort York National Historic Site

“Commemorate the 211th Anniversary of the Battle of York with special tours and demos! Traverse the grounds and delve into stories of the battle that took place on-site, its participants and its impact on the land and peoples. Learn about Indigenous contributions in a battlefield tour, titled ‘The Anishinaabeg Defenders of York.’ Excite your imagination by experiencing historic musket demonstrations, historic kitchen animations, displays and more!”

Free!

ANISHNAABEG: AFTER 200 YEARS “THE PEOPLE” STLIL ENDURE

April 28 — 6pm — Lambton House — Heritage York

Heritage York’s annual fundraiser dinner. “Andrew McConnell, a member of Nipissing First Nation, who worked in media, is a teacher and a PhD Candidate, will speak on Ojibwe language, culture and history - Only 45 tickets will be available.”

$60

MIMICO CREEK WALK AT MONTGOMERY’S INN

Various dates until April 28 — 11:30am — Montgomery’s Inn

“Learn about the history of Mimico Creek and its local communities, changing land use around the creek, and the protection of the local watershed as we celebrate environmental sustainability this month. This guided walk through Tom Riley Park is weather permitting.”

Free!

CHERRY BLOSSOM SEASON AT COLBORNE LODGE

Until April 29 — 11am to 4pm daily — Colborne Lodge

“Come to Colborne Lodge to celebrate Cherry Blossom season! Learn about the history of the cherry trees in High Park and enjoy reproductions of 19th century Japanese art and poetry depicting this seasonal celebration. Check out haikus created by High Park visitors and add your own haiku to the display.”

Free!