A Lovestruck French Aristocrat in the Skies Above Toronto

Plus the city's deadliest heatwave, Toronto's founding cat, and more...

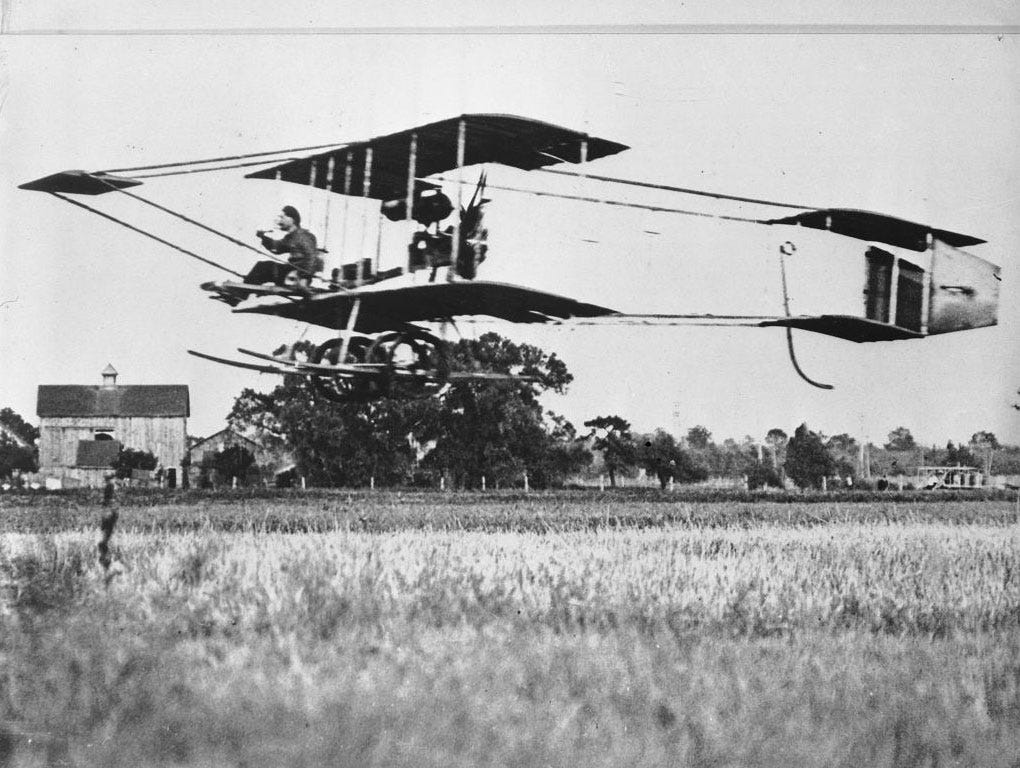

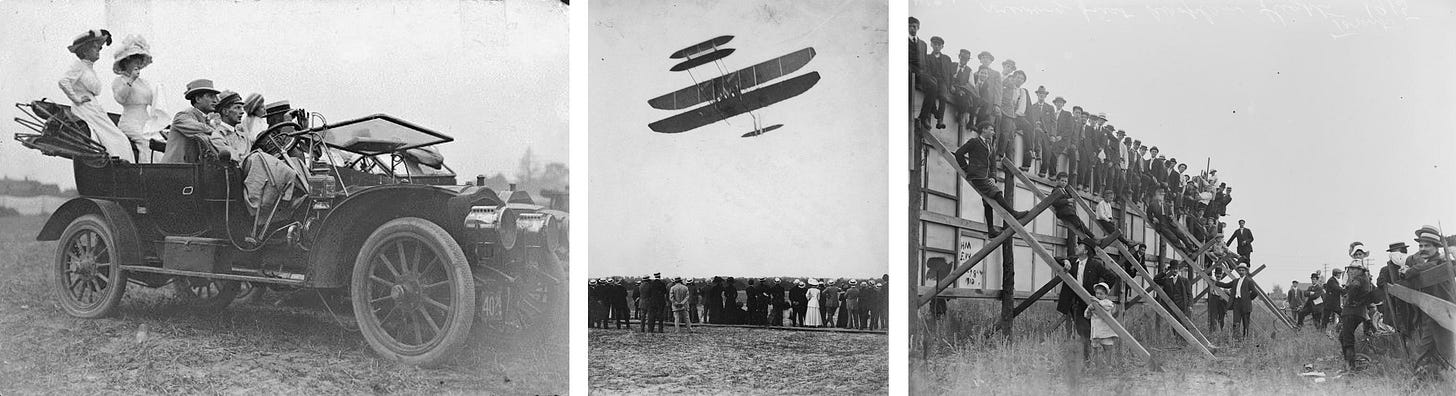

The summer of 1910. Crowds have gathered at a farm just outside the town of Weston — near the corner of Jane & Lawrence. They stand in the pea fields, perch on fences, sit in the new grandstand built for the occasion or in the seats of the automobiles they’ve driven out onto the grass; others clamber up on a billboard to get a better view. Their eyes are turned to the sky. Above them, Toronto’s first aviation meet is under way; some of the earliest airplanes ever built are putting on a show.

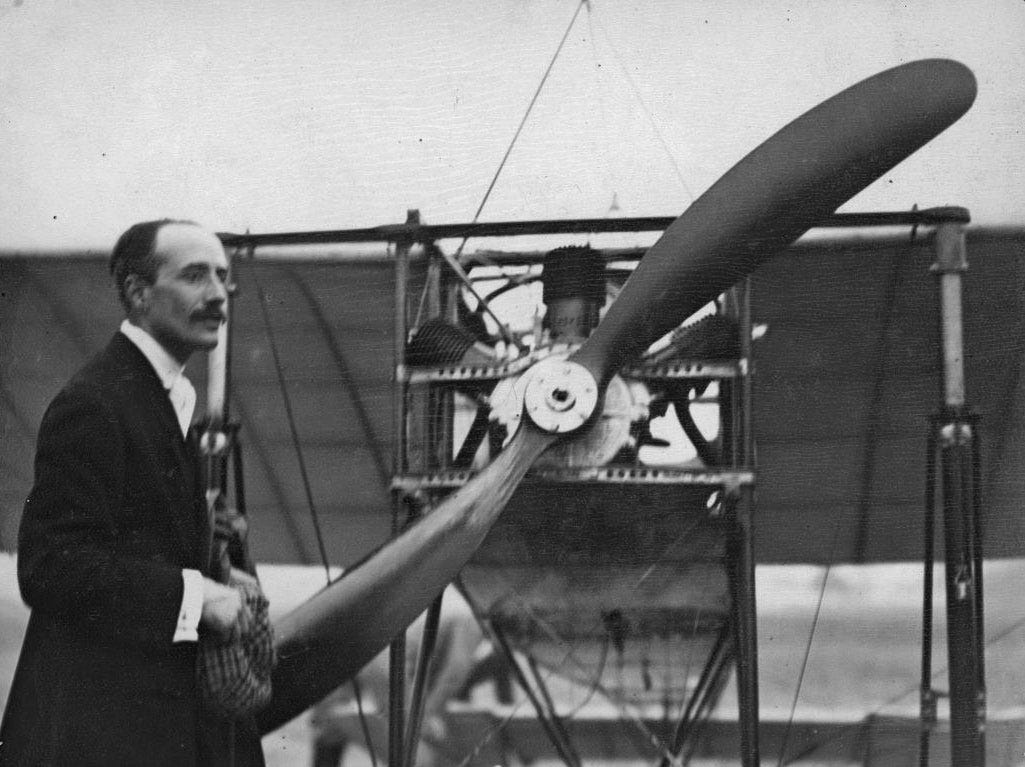

The star of the day was an adventurous young man named Jacques de Lesseps. He was a French count, the eldest son of the diplomat who spearheaded the construction of the Suez Canal. Just a few months earlier, he’d become one of the first people in the world to get a pilot’s license. He’d been the second aviator to fly across the English Channel, and would go on to become the first pilot to land a plane at night and the first to fly over the Statue of Liberty (a particularly symbolic moment, since it was his father who had presented the monument to the U.S. as a gift from the French people). And as his rickety craft bounced across that pea field outside Weston and lifted off awkwardly into the sky, de Lesseps was on his way to making even more history. He would spend the next twenty-eight minutes in the air, climbing more than three thousand feet into the sky — by far the most spectacular flight of the meet. Before turning for home he would make it all the way downtown, becoming the first person ever to fly above the heart of our city.

But that wasn’t even the most exciting part of his week. While he was in Toronto, the aristocratic aviator met the woman he was going to marry.

Her name was Grace Mackenzie. She was the daughter of one of the city’s most powerful men. Sir William Mackenzie was one of three famous Torontonians with the same name; he’s not to be confused with the city’s first mayor, William Lyon Mackenzie, or Canada’s longest-serving prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King. No, this William Mackenzie was the one who was hailed as “The Railway King of Canada,” co-founder of Toronto’s private streetcar company and the president of the Great Northern Railway — the second railroad across Canada, it would eventually become a big part of CN.

During his week in Toronto, de Lesseps was the guest of honour at a celebratory evening at the York Club (the old red brick mansion at the corner of Bloor & St. George). Mackenzie attended the event, and the railway baron was clearly impressed by the French aeronaut. He invited the pilot to dinner. The night at the Mackenzie mansion on Avenue Road went so well that the aviator then joined the family on their yacht for a tour of the Trent Canal. Not only did it give de Lesseps a chance to get to know the King of the Railways — but all three of his daughters, too.

Grace was the youngest, twenty-two-years-old. It’s easy to imagine why she would have been attracted to the Frenchman. “Wherever he went,” author Elizabeth Gillan Muir once explained, “women swooned.” De Lesseps was wealthy and aristocratic. Slender and handsome, with what The Globe called “a gentle, dreamy quality.” And above all else, he was brave and adventurous.

This was an age when aviators were hailed as heroes. Airplanes were still a breathtakingly new invention; it had been less than a decade since the Wright Brothers’ pioneering flight. The first Canadian airplane had taken off just a year before the Toronto aviation meet. It was called The Silver Dart, built by a team of five inventors led by Alexander Graham Bell. They called themselves the Aerial Experimental Association and included two graduates from the University of Toronto (one of them the grandson of Robert Baldwin, the famous champion of Responsible Government). When the aircraft of bamboo, wire, tape and steel raced across the frozen ice of Bras d’Or Lake in Cape Breton and lifted off into the air, it became the first plane to fly anywhere in the British Empire.

Toronto’s first flight came just months after that. Charles Willard was an American pilot who learned to fly from one of the inventors of The Silver Dart. He brought his plane to our city in September of 1909, invited to wow the crowds at the Scarboro Beach Amusement Park. Things didn’t go particularly smoothly. On his first attempt, Willard barely got into the air before splashing down into the lake. On his second attempt, he sailed high above the water and made a big loop through the sky — only to discover there was no room for him to land on the beach; it was filled with the crowds who’d gathered to watch. So, he was forced to come down in the lake once again.

Willard’s wet landings were a reminder of just how dangerous flying really was. One member of Alexander Graham Bell’s team was killed before they even finished building The Silver Dart. Thomas Selfridge was in the passenger seat on a disastrous flight with Orville Wright. When a propellor broke, the plane nose-dived into the ground. Selfridge suffered a fractured skull, becoming the first person ever to die in a plane crash.

Jacques de Lesseps was doomed to meet a similar fate — though when Grace Mackenzie first met him, his life of danger and excitement must only have added to the thrill of the romance. In fact, it was only a few months later that she would fly herself.

Her big chance came when her parents left on a business trip. She and her sisters seized the opportunity to sneak away to New York City, where the dashing young aviator was taking part in another air show. They joined him at the Belmont Park racetrack where it was being held — and where, according to The Toronto Daily Star, Grace became “an almost constant visitor at the De Lesseps’ hangers.” Barely any women had ever climbed aboard an airplane; even decades later, the president of the Regina Flying Club would claim that “women’s only place in flying is as the mother of the pilots.” But that wasn’t about to stop Grace Mackenzie. When de Lesseps took her on a flight above New York, she became the second Canadian woman ever to fly in an airplane. Her sisters got their own turns later that same day. Grace loved it so much, she even went up again for a second flight.

Her father, however, was not impressed. When he saw the headlines about daughters’ exploits, Sir William Mackenzie sent them a stern telegram: “COME HOME AT ONCE.” But it was too late. By then, the press was already reporting rumours that Grace and Jacques were engaged to be married — and those rumours turned out to be true. The wedding was held in London a few months later, a big splash with a long guestlist filled with notable names and a crowd of spectators gathered outside the church hoping to catch a glimpse of the famous young couple. To get Mackenzie’s blessing, de Lesseps is said to have promised he would give up his dangerous life of flying. But it’s a promise he didn’t keep. He would die doing what he loved.

The newlyweds began their new life together in Paris, but as they did the clouds of war were gathering. It was only three years into their marriage that the First World War broke out. Pilots were now being called upon to take the fight into the skies. Airplanes had only existed for a decade, but it hadn’t taken long for people to imagine their potential as flying machines of death. At the aviation meet in Toronto, one pilot performed a military demonstration, dropping a gingerale bottle from the sky to simulate a bomb; the organizers even set off an explosion when it hit the ground. During the war, our city would become an important hub for the Royal Flying Corps, teaching new recruits how to fly — and how to kill.

Life as an air force pilot was incredibly dangerous; the average life expectancy in the Royal Flying Corps was only eleven days. But de Lesseps was a born daredevil. He quickly joined the French Armée de l'Air. He commanded his own squadron, often flying under the cover of night, defending Paris against the bombing raids of Germany’s Zeppelin airships. He flew dozens of missions, soaring over the frontlines, buzzing low over the ground on bombing runs, snapping photos of railroads and chemical plants from the air. He risked his life over and over again. By the time the war was done, he’d earned eight citations for bravery and been decorated by both France and the United States.

Grace had done her part, too, working in a hospital as a volunteer nurse. And after the war ended, the couple themselves back in Canada. The count called upon his wartime experiences as a reconnaissance pilot to launch a new career as an aerial photographer. He’d miraculously survived the horrors of the war, but he wouldn’t survive his new business.

It was in 1926 that he was hired by the government of Québec, spending the next two summers soaring above the forests of the Gaspé peninsula. He assembled a small fleet of flying boats, early sea planes, becoming the first person to ever to see the area from above. He took more than a thousand photographs covering nearly 25,000 square kilometres, allowing the province to create accurate maps of the region.

The French aristocrat fell in love with that land. “You cannot imagine the magnificent and moving spectacle that one can have in the skies of Gaspé,” he wrote to a friend. “And what a marvellous sight is offered by the contrast of colours between the vast peninsula and the sea that bathes it: on one side, velvet green and silky forest, artistically draped according to the whim of the mountains and valleys; on the other, the blue of the sky united with the blue of the gulf dazzling in the sun.”

It was there, in that place he loved so deeply, that Jacques de Lesseps would be killed.

His final flight came on an October afternoon in 1927. He lifted off from Gaspé with his Russian mechanic, Theodore Chichenko, on what promised to be a routine flight. It wasn’t until after they left that a call came in: a storm was gathering above the St. Lawrence. De Lesseps was last spotted by the residents of a small village on the banks of the great river, fighting to keep his plane airborne as he disappeared into the tempest. In the coming days, pieces of his airplane began washing up on shore. A desperate rescue effort was launched, hoping against hope that the aeronaut and his mechanic would be found alive. But after days of searching, there had been no sign of them. The hunt was called off.

By then, Jacques and Grace had been apart for years. She was living in Toronto now, in a mansion in Rosedale. That’s where the family waited for the terrible news that finally came seven weeks after the storm. The body of Jacques de Lesseps had been found floating in the waters of Newfoundland, hundreds of kilometres from where he’d died. He was laid to rest in the town of Gaspé, on the peninsula he loved, where today you’ll find a monument erected in his honour.

For nearly two decades, he had defied death and gravity. He’d written himself into the history of aviation — and into the history of countless communities on both sides of the Atlantic. Including Toronto.

On that day in Weston, he’d risen nearly a kilometre into the sky — so high the air began to thin and the temperature to drop. He headed south over Mount Dennis and the Junction and High Park, alone with the spectacular views and the whirring hum of his craft. He reached Humber Bay and banked to the left, soaring over Hanlan’s Point as he made the turn toward home. As he flew above Spadina Avenue, traffic came to a stop. People poured out of streetcars to watch him pass by, craning their necks skyward to catch a glimpse of the first person ever to fly over our city. The Telegram called it, “The greatest sight of the twentieth century in Toronto.”

By the time the flying Frenchman made it all the way back to Weston, dusk had begun to descend. A barrel of gasoline was set alight, a glowing beacon to guide him home. The crowds watched as he floated down out of the sky toward the rough runway carved out of the pea field. And as he touched down safely and slowed his airplane to a stop, they broke into applause and rushed out to greet him. They lifted him onto their shoulders and wrapped him in the French flag, cheering and roaring in celebration. They had just witnessed history. Jacques de Lesseps had done something no one had ever done before.

If you’d like more stories about love, death and Canadian history then boy oh boy do I have an online course for you… You’ll find the details below.

David Wencer wrote a wonderful piece about the aviation meet for Torontoist, which you can still find it thanks to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine here. Elizabeth Gillan Muir wrote a whole book about “Canadian Women In The Sky.” You can find it here. Gaspé Of Yesterday has an article about de Lesseps here. And you’ll find some of The Toronto Daily Star’s coverage of his exploits, romance and disappearance here and here and here. (I’m hoping those last three links work, but I’ve never tried to link directly to those archives before, so my apologies if they don’t.)

Love, Death & Canadian History — My New Online Course!

Canadian history is much more than dry lists of dates and events. It's filled with gripping tales from the lives of historical figures who were people much like us — who fell in love, suffered broken hearts, were fascinated by death and devastated by loss. Those stories of love and death have a lot to teach us about our country. In this ten-week online course, we'll explore the history of this place from time immemorial to the recent past, uncovering torrid affairs and shocking scandals, duels, murders and executions. And we'll discover the ways in which those passionate and morbid tales have shaped the country we live in.

The course will kick off on the night of Thursday, July 20. And if you’re interested but concerned you might have to miss some classes, don’t worry — all the lectures will be recorded and posted to a private YouTube playlist so you can watch them whenever you like. Oh, and paid subscribers to the newsletter get 10% off!

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber to the newsletter and you’d like to make the switch, all you have to do is click the button below. This newsletter is a ton of work! Only about 4% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 25 other people — in addition to getting perks like 10% off my online courses:

The Deadliest Heat Wave In Toronto History

During this week 87 years ago, Toronto was absolutely sweltering. The city’s deadliest heatwave had arrived, with record temperatures soaring above 40°C. It was so hot people fled their homes and slept on beaches while the roads literally warped and buckled. By the time the heat finally broke, it had claimed more than 200 lives in Toronto alone. I wrote about it all for Torontoverse this week, giving you a tour of what was happening across the city during that tragic week. It’s a story with details that are truly hard to believe.

Toronto’s Founding Cat

I also re-shared an old story on Twitter this week. Toronto’s founding cat arrived in our city 230 years ago this month — a fascinating pet belonging to the Simcoe family. blogTO then picked up on the story and wrote about my thread this weekend... (Giving the newsletter a nice little boost in subscriptions in the process. Welcome to all the new readers!)

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

CHINESE EXCLUSION ACT NEWS — Last week, I mentioned Canada Day marked the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Jamie Bradburn wrote about it for TVO this week. Read more.

WET NEWS — Toronto’s got a new historical walking tour company thanks to Matthew Jordan, who has already brought the history of our city’s lost waterways to TikTok — and is now doing it in person, too. Emma Johnston-Wheeler interviewed him about his new Hidden Rivers Walking Tours this week. Read more.

SLOW BALL NEWS — One of the greatest seasons for a relief pitcher in the entire history of baseball was thrown by a Toronto Blue Jay. In 1986, rookie sidearmer Mark Eichhorn absolutely dominated hitters — even though his pitches were incredibly slow. The “Look, It’s Baseball” YouTube channel tells the story. (I’ve haven’t had a chance to watch it out myself yet, but am really looking forward to checking it out.) Watch it.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

ON THE EDGE OF A CITY: TORONTO IN 1833 WALKING TOUR

August 19 — 10:30am — Meet at St. James Cathedral — Town of York Historical Society

“In this walking tour, explore the surviving built environment of the original 10 blocks of Toronto and discover how the Town of York, which started with a population of a couple hundred residents, became the City of Toronto in 1834, with a population of just under 10,000.”

$17.31 for non-members; $11.98 for members

DEATH, VIOLENCE & SCANDAL IN YORK WALKING TOUR

August 19 — 2pm — Meet at St. James Cathedral — Town of York Historical Society

“In this walking tour, explore the scandalous side of Little Muddy York as we walk through the surviving built environment of the original 10 blocks of Toronto and learn about the intriguing stories that would have been the gossip of the day.”

$17.31 for non-members; $11.98 for members

MR. DRESSUP TO DEGRASSI: 42 YEARS OF LEGENDARY TORONTO KIDS TV

Until August 19 — Wed to Sat, 12pm to 6pm — 401 Richmond — Myseum

“The TV shows of your childhood hit closer to home than you might think. From 1952 to 1994, Toronto was a global player in a golden era of children’s television programming. For over four decades, our city brought together innovative thought leaders, passionate creators and unexpected collaborations – forming a corner of the television industry unlike any other in the world. Toronto etched itself into our collective consciousness with shows like Mr. Dressup, Today’s Special, The Friendly Giant, Polka Dot Door, Degrassi, and more. Journey through Toronto’s heyday of children’s TV shows in this playful exhibition.”

Free!

ROOT OF THE TONGUE BY STEVEN BECKLY

Until August 27 — Wed to Sun, 11am to 5pm — Montgomery’s Inn

“Root of the Tongue is an exhibition of new artworks by Steven Beckly. Situated within Montgomery’s Inn, it consists of evocative images, sounds, and sculptural objects inspired by the Chung family, Chinese market gardeners who resided there in the 1940s. Considering their intimate roots to the site as well as the racism and xenophobia they faced during that time in Canada, Root of the Tongue explores the vegetable garden as fertile grounds for rituals of care and cultivation, ripe with symbolism and queerness.”

Free!