A Canadian Who Survived The Titanic

Plus an absurd & unlikely death, the origins of baseball's colour barrier, and more.

This week in 1912, the unsinkable Titanic sank. This week in 2022, we’ll talk about one of the Canadians who survived the disaster, learn about an absurdly unlikely death, look into the leading role Toronto played in the creation of baseball’s colour barrier, and more.

But before we begin: Thanks so much to everyone who joined as a new subscriber this week! There are a whole big lot of you, which is very exciting! I launched this newsletter earlier this year to share stories and tidbits from the history of the city, plus interesting links, event listings and more. The response so far has been absolutely amazing. And I can’t thank everyone enough for their support.

It is a TON of work, though, so The Toronto History Weekly will only be able to survive if enough of you are willing to switch to a paid subscription. It’s just a few dollars a month to support the newsletter and all the work I do, plus you’ll get some fancy extras like discounts off my online courses, invites to exclusive online talks, the ability to comment on these posts, and more fun stuff I’m continuing to dream up. You can switch to a paid subscription by clicking right here:

And if you don’t think a paid subscription is for you, don’t worry! I’m thrilled to have you all reading along! Thanks to every single one of you!

Now, let’s get started…

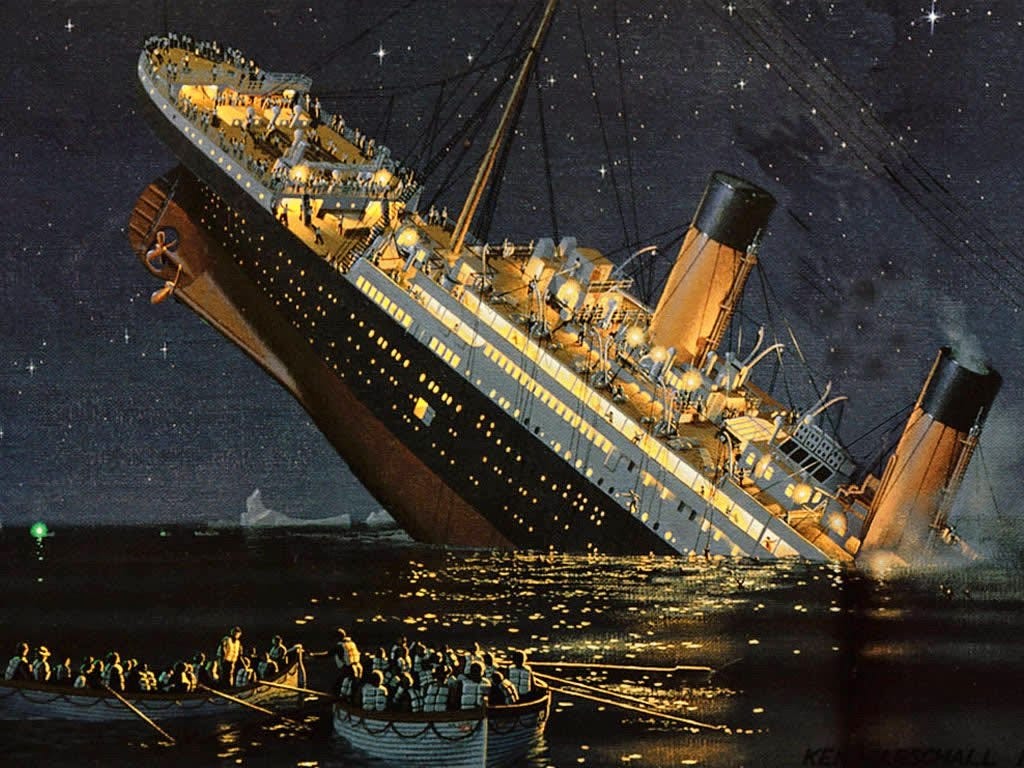

UNSINKABLE NEWS — It was 110 years ago that the Titanic sank beneath the frigid waves of the North Atlantic. The infamous ship took twenty Canadians down with it, more than half of the canucks on board. I wrote about some of them on Twitter this week, sharing the story of a surprising discovery made by a Soviet submarine as it explored the wreck decades later: twelve tickets for the Toronto streetcar.

You can check out that thread here.

But today, I thought I’d tell you about one of the Canadians I didn’t mention in that thread: a woman who survived the sinking and eventually moved to Toronto, living a long life before finally being laid to rest at Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Her name was Mary Fortune. She was born not far outside Toronto, but soon moved to Manitoba where she fell in love and got married. Her husband was a business tycoon with an appropriate family name: Mark Fortune had made an absolute fortune in real estate. And in 1912, the Fortunes decided to enjoy their wealth by taking their children on a lavish tour of Europe and the Middle East, setting out from Winnipeg to see the world.

The trip was supposed to be a happy occasion, but there was at least one troubling omen. It came in Cairo, when one of Mary’s daughters received a chilling warning from a fortune teller: “You are in danger every time you travel on the sea, for I see you adrift in an open boat. You will lose everything but your life.”

It was just a few weeks later that the Fortunes boarded the Titanic to make their voyage home.

Mary was asleep in her first class cabin when the ship struck the iceberg, woken by the force of the collision. When the Fortunes learned what had happened, the family headed up toward the deck, toward the lifeboats, toward safety... But as they reached the stairwell, they were stopped by members of the ship’s crew. Only women and children were allowed above, the officers explained; until they were safely evacuated, the men would have to stay below.

The Fortunes had no idea how quickly the ship was sinking, how little time was left for them to make their escape. They didn’t even say a proper goodbye. As Mary and her daughters headed up to the deck, Mark and their son Charles stayed behind. Later that night, Mark would be spotted on deck wearing his favourite bison fur coat from Winnipeg, happy it was keeping him warm in the cold April air. Mary had tried to talk him out of bringing it, figuring it would be useless in the heat of Egypt. He’d refused since it was a good luck charm; now its warmth was paying off. Those must have been the final few happy moments of his life. Death was drawing near.

By the time the Fortune women reached their lifeboat, some passengers were already getting desperate. A few men had tried to rush the crew as the boats were being loaded. Mary watched as the officers struggled to hold back the mob, firing their guns into the air as a warning before eventually opening fire on the angry, frightened passengers themselves.

Despite the chaos, Mary made it into a lifeboat with two of her daughters. But her third daughter was missing. Ethel hadn’t taken the danger seriously at first; she returned to her cabin before a steward was finally able to change her mind. The lifeboat was already being lowered over the side by the time she arrived.

By then, it was clear the ship was doomed; there was no time left, the lifeboat couldn’t wait for her. She had to jump to make it, leaping over the side of Titanic, dropping through the empty air toward the lifeboat, caught by those already on board. And she wasn’t the only one who risked her life to get into that boat. A few more passengers jumped. One woman missed and nearly fell to her death. Even a baby was thrown aboard.

But at last the Fortune women were safe. As the lifeboat pulled away, Mary looked back toward the sinking ship. She could see the band still playing on deck, life preservers secured around the musicians’ waists. The sound of ragtime rang out across the dark waves.

The lifeboat was crowded. And not just with women and children. There were a few men, too, including one wearing a skirt, a bonnet, a blouse and a veil; a makeshift disguise that allowed him to sneak aboard. He refused to give his name. Some men who survived the wreck would spend the rest of lives being reviled and ostracized, even those who were only doing their duty or trying to save other lives.

The Fortune women helped row the boat away from the massive sinking titan next to them. It was nearly an hour later that they watched the stern of the goliath rise up into the air. They could hear the screams. The ship’s lights flickered, then went dark. Then the great hull split apart with a deafening crack and disappeared beneath the waves.

The Titanic took more than 1,500 people down with it, including twenty Canadians. Mary’s beloved Mark and Charles were gone.

Then, the surviving Fortunes waited. And waited. And waited. As dawn broke over the Atlantic, they were still drifting across the ocean in that lifeboat. It was eight in the morning before the Carpathia finally arrived to rescue them. Theirs was the second-last lifeboat saved.

Mary, heartbroken, never remarried. It was toward the end of her life that she moved back to Toronto. And that’s where she died, at the age of 77, nearly two decades after the infamous disaster that nearly claimed her life.

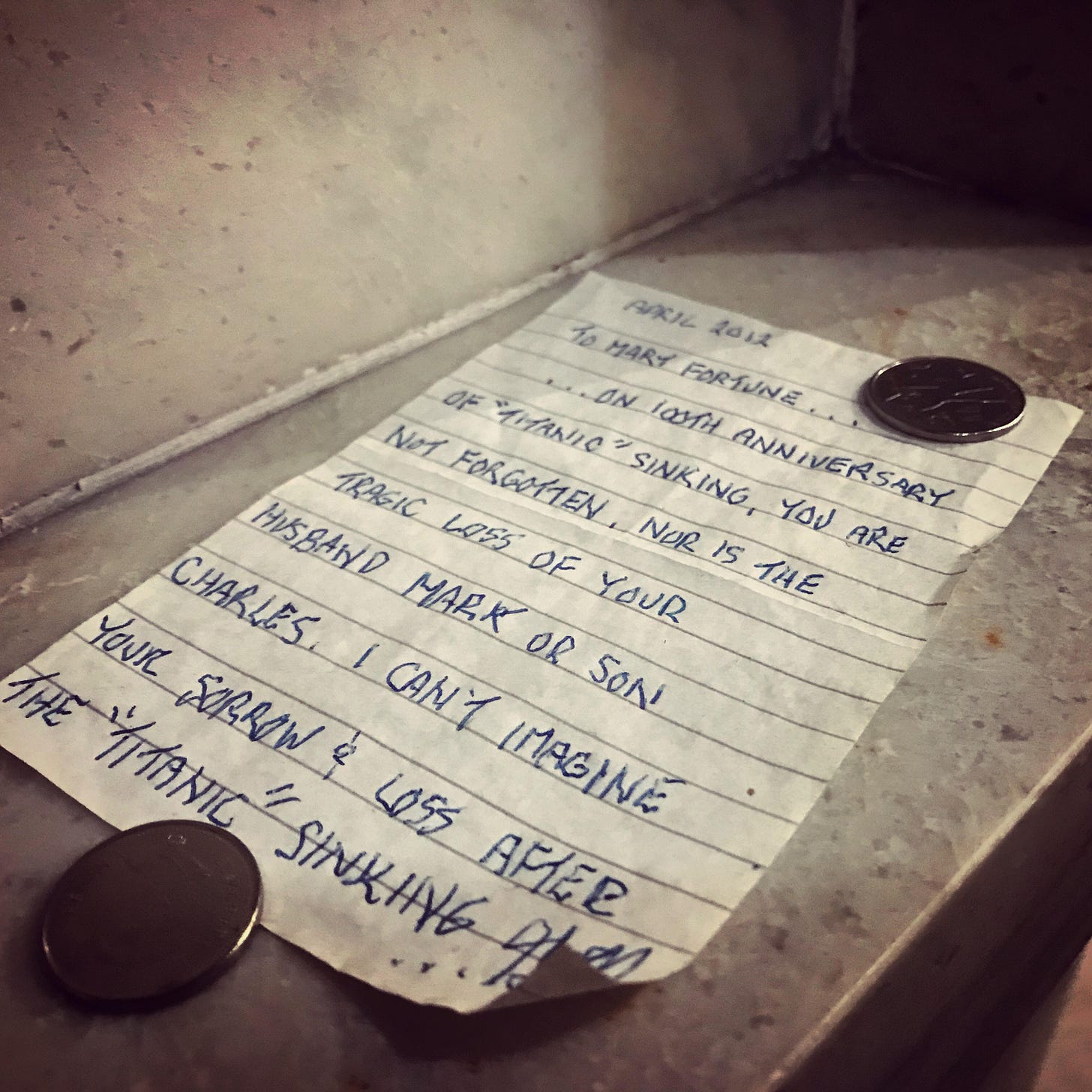

She was laid to rest at Mount Pleasant Cemetery. I paid her a visit there a few years ago, venturing inside the mausoleum as darkness descended on the gravestones that surround it. And there at Mary Fortune’s crypt, I found a message someone left for her a decade ago, placed there on the 100th anniversary of the sinking. It’s a simple, loving note, assuring the spirt of the heartbroken widow that she — and her terrible loss — have not been forgotten, even after all these years.

AN ABSURD & UNLIKELY DEATH

UMBRELLA NEWS — This week was our second class in the online course I’ve been offering this month: Toronto’s Most Notorious Murders. And I thought I’d share a little tidbit I stumbled across during my research.

One of the most notorious murders in Victorian Toronto was the killing of Frank Westwood — a wealthy Parkdale teenager gunned down by a mysterious assailant. The search eventually led police to Clara Ford, a fascinating figure who seems to be one of the few trans people we can clearly see in the historical record that far back in the city’s past. But it’s the lawyers in the court case that followed that I wanted to tell you about today.

The lead prosecutor was a man named Britton Bath Osler. He was from a famous family — his grandfather seems to have been a pirate, but the Oslers were now one of the most respected names in Canada. One of Britton’s brothers was a world-renowned doctor, another a politician, and a third a judge. He himself was one of the best-known lawyers in Canada, having made national headlines as one of the prosecutors who got Louis Riel convicted and hanged after the Northwest Resistance. And years before that, he’d been celebrated as a hero after a gas explosion tore through his home. As his house burned, Osler risked his life to rush back and save his maid from the flames, rolling her in a carpet to put her out, getting horribly burned in the process. He’d be scarred for the rest of his life and would never regain the full use of his limbs. His wife never recovered from her own wounds; halfway through the trial she passed away. Her grief-stricken husband was forced with withdraw, leaving the prosecution in disarray.

But it’s one of Ford’s defence lawyers that prompted the headline above. William G. Murdoch was another one of Toronto’s most respected lawyers. But his life would end tragically — and in absurd fashion.

Murdoch was said to have a good sense of humours. And it was that joyful approach to life that spelled his doomed. One days, while playing with a friend things went horribly wrong. They were pretending to have a sword fight with their umbrellas when his friend’s umbrella must have slipped. It went through Murdoch’s eye and killed the lawyer dead.

As for the murder of Frank Westwood, we’ll never know the truth of what happened. Murdoch and the rest of the defence team took advantage of the chaos sown by Osler’s absense, managing to convince the jury that Clara Ford’s confession had been invented by the police — a strong argument in a city where the police force had often been accused of corruption. Cheers broke out in the courtroom and outside a crowd lifted the acquitted murder suspect onto their shoulders in celebration. But most historians who’ve looked at the evidence seem to agree that there’s very little question Ford really was the murderer.

If you’ve missed out on the course this time around, don’t worry! I’m hoping to bring it back in the fall. And if you’d like me to let you know when I do, feel free to reply to this email and I’ll be sure to give you a heads up! (And if you’d like to see what other online courses I offer from time to time, you can check ’em all out here.)

TORONTO HELPED DRAW BASEBALL’S COLOUR LINE

DISTURBING NEWS — It was during this week in 1947 that Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s Major League colour barrier. So I thought I’d mark the occasion by sharing a thread about a disturbing new fact I learned a few months ago while I was putting together an online course about the history of baseball in Toronto: that our city played a leading role in creating that colour barrier in the first place.

You can read the full thread here.

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

LOG CABIN NEWS — blogTO shares a quick look at Scadding Cabin, the oldest building in Toronto, on Twitter. Originally built in the Don Valley in the late 1700s, it’s now at the CNE. Check it out.

SIN STRIP NEWS — A new book by Daniel Ross, The Heart of Toronto, takes a look at a quarter century of efforts to remake Yonge Street from the old days when it was the notorious “sin strip” — a history that stretches back all the way to the 1950s. Read more.

GHOST SIGN NEWS — Katherine Taylor is the go-to source on Twitter for people who love to spot the ghostly remains of painted signs on Toronto’s old buildings. And she shared another couple of ghost signs this week. Check them out.

HOLD THE ANCHOVIES NEWS — Bob Georgiou (@BobGeorgiouTO on Twitter) stumbled across some anonymous hero’s map of Toronto from the 1950s to the 1990s. Check it out.

PHILATELIST NEWS — Salome Bey, hailed as “Canada’s First Lady of the Blues,” is being remembered with her own stamp from Canada Post. It’s gonna be unveiled on Thursday. Read more.

BOOM-CHK-BOOM-CHK-BOOM NEWS — At blogTO, Phil Villeneuve shares a list of “The 27 most memorable night clubs in Toronto’s history.” I immediately checked to see if Sparkles, the 1980s dance club where you could party long into the night high above our city inside the CN Tower, made the list. And it did! Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

GLORY DAYS: 200 YEARS OF TORONTO SPORTS SOUVENIRS

April 20 — 6pm — Online — Heritage Toronto

“April marks an important time for sports in Toronto: baseball season begins while hockey and basketball playoffs kick off. Join Matthew Blackett and Wayne Reeves, co-editors of Spacing’s “Souvenirs of Toronto Sports,” to discuss Toronto’s ongoing love of sports, illustrated through rarely-seen artifacts held by the City of Toronto collections.”

Free with registration.

SCURRILITY AND STREET NAMES

April 21 — 7:30pm — Online — Etobicoke Historical Society

“Richard Fiennes-Clinton takes a light-hearted look at King George III, and some of the connections that existed between the Royal Family the old Town of York, between the 1790s and the 1830s. George III is remembered as the King who lost the American Revolution, and who suffered from bouts of “madness”. But George III was also a family man, who tried to instill domestic virtues in each of his 15 children. But when the King died in 1820, his eldest sons embarked on a "Royal Baby Race" to provide an heir to the Kingdom. The Royal Family were the inspiration for street names in early Toronto, many of which remain today.”

Free for members; an annual membership is $25.

REFASHIONING & SUSTAINABILITY WEEKEND: MACKENZIE HOUSE

April 23–24 — Various Times — Mackenzie House Museum (82 Bond Street)

“How did 19th century printers in Toronto recycle materials to avoid waste? In a 45 minute program, participants learn about 19th century recycling and how it both parallels and differs from the sustainability ethos of today. Visitors will see demonstrations of printshop equipment and take home personalized souvenirs from the 1845 printing press.”

Free.

REFASHIONING & SUSTAINABILITY WEEKEND: COLBORNE LODGE

April 23–24 — Various times — Colborne Lodge (11 Colborne Lodge Dr., High Park)

“Learn how textiles were produced before modern manufacturing and the environmental impact of these processes. Participants will learn about the characteristics of natural fibres and the processes to turn them into cloth.”

Free with ticket.

THE DISCOVERY OF INSULIN WITH JOHN LORINC

April 26 — 6:30pm — Online — The Riverdale Historical Society

“The story of the discovery of insulin, at the University of Toronto in 1921, has become one of the most mythologized narratives of Canadian science, and triggered a revolution in the treatment of a horrendous disease that was a death sentence for many sufferers. Yet the mythology has obscured much of what really occurred in the lab run by Banting and Best — e.g., the conflicts within the wider research team, the role that early vaccination research played in their work — as well as the long-tail lessons associated with the discovery of insulin, including the role of the profit motive in drug development and the importance of domestic testing and production infrastructure. The centennial surfaced some of these angles, and the COVID-19 pandemic has served as a reminder about what was lost when Canada divested the Connaught Labs, which played such an integral role.”

Free if you join the Riverdale Historical Society mailing list.

FIDDLEHEAD FERNS & LOYALIST LAGER: HOW FOOD BUILT TORONTO

April 27 — 7:30pm — Online — The North Toronto Historical Society

“What was the food scene of early Toronto, long before its celebrity chefs and foodie festivals? In this presentation by Dr. Laura Carlson, we’ll take a long look at Toronto’s foodways: from ancient Indigenous cuisines to the city’s earliest public markets. We’ll explore how food and drink shaped the very streets of early Toronto, playing a role in everything from politics to economics to culture. Finally, we’ll hear about some famous Torontonians who built their reputations on keeping the city well fed.”

Free with registration, I believe.

SCURRILITY AND STREET NAMES

May 19 — 7:30pm — Online — Etobicoke Historical Society

“Frederick Banting once wrote, “Insulin was but a means to an end.” After receiving Canada’s first Nobel Prize, insulin did become a means to an end. Unfortunately for Banting, that end was a legacy from which he desperately attempted to distance himself.

“The story of Frederick Banting is well known, but not necessarily known well. While his name has become synonymous with the discovery of insulin, there was far more to this distinguished Canadian’s career than the often-simplified events of the insulin period. Grant Maltman will highlight insulin’s centenary and introduce other aspects of his life and career including his service in both World Wars, his use of art as an escape, and his role as a catalyst for Canada’s military and medical research programs.”

Free for members; an annual membership is $25.