A Brief History of the Pigeons of Toronto

Plus a new name for Black Creek Pioneer Village, a spectacular new use for some old silos, and more...

Pigeons have been living with people for as long as anyone can remember. They were among the first animals humans ever domesticated — back in the days of prehistory. Pigeons are already there in some of the oldest records we have: Egyptian hieroglyphics, Mesopotamian tablets from five thousand years ago, the epic of Gilgamesh.... Julius Caesar and Genghis Khan used them to send messages during battle. The ancient Greeks used them to announce the results of the first Olympic Games. The Greeks and the Romans and the Phoenicians all used them as a symbol of the goddess of love. White doves, which are really just white pigeons, are still a symbol of peace today.

The domestic birds were selectively bred over thousands of years into a kaleidoscope of colours and characteristics. But they’re all descended from wild rock doves. The species has been around for about twenty million years — so, about a third of the way back to the dinosaurs (when we were still living in trees). They evolved in Asia before spreading to Europe and Africa and they’re still around today. They all look pretty much like your standard template pigeon: blue-grey with black stripes on their wings and iridescent purple-green necks. They live on sea cliffs and on mountainsides, and thanks to their super-powers they can almost always find their way back home. Scientists think pigeons might be able to sense the Earth’s magnetic field. And they’re crazy-smart, too: you can train them to recognize the letters of the alphabet and their own reflection in a mirror. One scientist taught them to tell the difference between a Monet and a Picasso. They’re smart enough to use landmarks to find their way home.

That homing instinct is what made pigeons such a useful species to domesticate: if you want to send a message, you can just take a pigeon to the place you want to send the message from and then let the bird fly home with it. They can cover thousands of kilometres. They’re fast, too: they can get up to almost a hundred kilometres per hour over short distances. That’s faster than a cheetah.

Some of those domestic pigeons never did fly home, though. Instead, they went feral. Back on the other side of the Atlantic, they’ve been doing it since the days of antiquity. In towns and in villages and in cities, they found tall buildings and temples and cathedrals that were a lot like the sea cliffs and mountainsides they were originally evolved for, using them to roost and nest. They also found lots of food. Pigeons can eat all sorts of things. And unlike most birds (or mammals, for that matter), both female and male pigeons can turn that food into a kind of regurgitated milk for their baby squabs. They grow up quick and they multiply fast. They can start pumping out babies when they’re just six months old and can do it over and over and over again. When conditions are right: six times a year.

They also, more adorably, mate for life.

It was the French who first brought them to the Americas. In 1606, a ship docked in Nova Scotia at the colony of Port-Royal, which had just been founded by Samuel de Champlain. On board were the very first rock doves ever to be shipped across the Atlantic. Champlain figured the birds would bring a touch of European civilization to New France — and make good meat pies. When he founded Quebec City a couple of years later, a pigeon-loft was part of the original settlement. As Europeans spread out across the continent, domestic pigeons — and their feral descendants — went with them.

But they weren’t alone. North America already had lots of pigeons before the Europeans arrived. There were passenger pigeons by the billions.

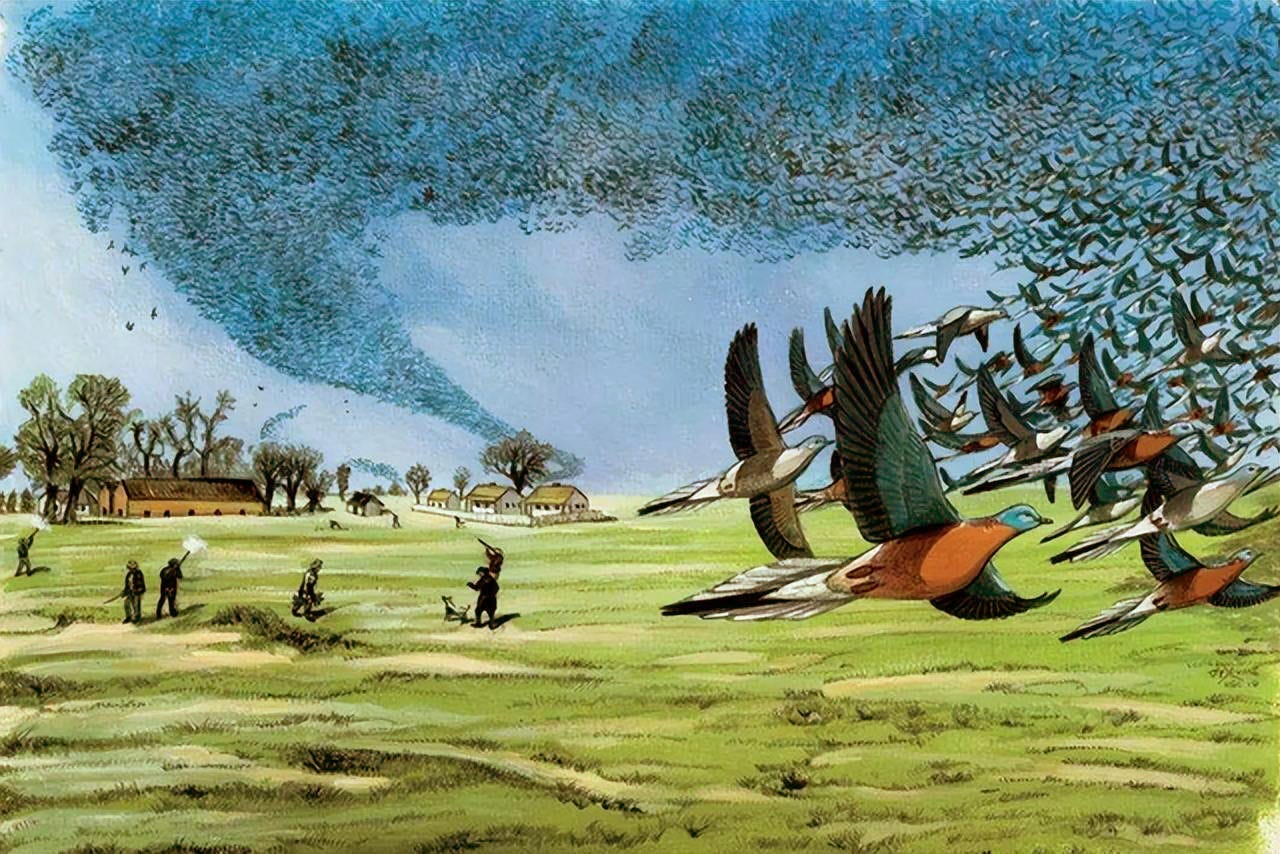

When Samuel de Champlain first arrived, they were everywhere. In his diary, he describes them as “infinite.” At their peak, there were flocks of millions of them flying all over the eastern half of the continent, including what we now call southern Ontario. Their nesting grounds covered vast stretches of forest. A single tree could hold a hundred nests; branches buckled and cracked under the weight while droppings covered the ground like snow. In the spring and in the fall, they would migrate in enormous numbers. One naturalist near Niagara-on-the-Lake watched a flock head south into the United States for fourteen straight hours. They formed a column a kilometre and a half wide and five hundred kilometres long. And that was nothing. Sometimes, they could blot out the sun for days.

Passenger pigeons were bigger than their rock dove cousins, with longer necks and longer tails. People called them “graceful” and “dashing.” Their colour was a little bit like a mourning dove’s or a robin’s: brownish-blue-grey on top with a pinkish-red breast. “When they flew to the east of you so that the sun shone on them there was a perfect riot of colour as they passed,” the Owen Sound Daily Sun Times wrote, “the sheen of their plumage in the evening sun was such that no words could be found to describe nor a painter to paint it. The flash of brilliant colour and the wonderful whirr of their wings in flight as they passed within a few yards can never be forgotten.”

One of the most stirring descriptions of the birds comes from Chief Simon Pokagon of the Potawatomi. He wrote about them in a newspaper called The Chautauquan in 1895:

If the Great Spirit in His wisdom could have created a more elegant bird in plumage, form, and movement, He never did.... I have stood for hours admiring the movements of these birds. I have seen them fly in unbroken lines from the horizon, one line succeeding another from morning until night, moving their unbroken columns like an army of trained soldiers pushing to the front. At other times, I have seen them move in one unbroken column for hours across the sky, like some great river, ever varying in hue; and as the mighty stream, sweeping on at sixty miles an hour, reached some deep valley, it would pour its living mass headlong down hundreds of feet, sounding as though a whirlwind was abroad in the land. I have stood by the grandest waterfall of America and regarded the descending torrents in wonder and astonishment, yet never have my astonishment, wonder, and admiration been so stirred as when I have witnessed these birds drop from their course like meteors from heaven.

He called them “the most beautiful flowers of the animal creation of North America.”

In Toronto, the birds most famously congregated on the banks of Mimico Creek in Etobicoke. They would rest there before making the flight south across the lake. In fact, that’s how Mimico got its name: it’s derived from the Mississauga word omiimiikaa, which means “abundant with wild pigeons.”

It wasn’t just Mimico, though. The birds were all over town. In 1793, Elizabeth Simcoe described flocks of passenger pigeons so thick you could tie a bullet to a string and knock them down with it. There are stories of enormous flocks flying up the Don Valley every spring, soaring over the Islands, and spending the night in the Beaches. In Don Mills, people remembered a flock that once took an entire morning to fly by. In Cabbagetown, they remembered one that took days. Children were paid to shoot at them, to scare them away from farmers’ fields. In Mimico, they said you could kill a dozen birds with a single shot.

When a flock passed through Toronto in the 1830s, hunters went on a killing spree. “For three or four days the town resounded with one continued roll of firing,” a writer later remembered, “as if a skirmish were going on in the streets.” At first, the authorities tried to control the slaughter, but soon they gave up: “a sporting jubilee was proclaimed to all and sundry.”

The area around Sherbourne and Bloor became known as the Pigeon Green, where hunters would wait for the birds to descend into the valley — bringing them within easy firing range. In the city’s early days, passenger pigeons were a staple of the Torontonian diet. They were fried, roasted, stewed, and turned into soups and pies.

The hunting of passenger pigeons became a major industry. The flocks had always been harvested by the First Nations, but now the slaughter was waged on a massive scale. At some sites in the United States, tens of thousands of birds were killed every day for months on end: shot, trapped in giant nets, poisoned with whisky, burned in trees set on fire to drive newborn squabs out of their nests. Entire railway cars were packed full of them and shipped away to be sold as meat and mattress stuffing. You could buy them nearly everywhere, including the St. Lawrence Market.

The hunts took a staggering toll. So did the logging industry, which grew by leaps and bounds in the 1800s, destroying the ancient forests where the pigeons lived. All over eastern North America, the birds were being wiped out at a breathtaking pace. In just a few short decades, they went from being quite probably the single most populous bird species on Earth to the brink of extinction. Some estimates claim there were a quarter of a million birds dying every day.

Many people refused to believe what was happening. As the number of passenger pigeons plunged, concerns about over-hunting were dismissed by critics as “ground- less,” “absurd,” and “without foundation.” Even some people who did admit the population was crashing refused to believe humans were responsible. They came up with alternative theories: some said the birds had all drowned in the ocean or in Lake Michigan; some said they’d flown away to Australia, or died in a forest fire, or froze to death at the North Pole.

By the end of the 1800s, the birds had almost completely disappeared from the wild. The Toronto Gun Club had to start shipping them in from Buffalo for their annual hunt. By the time the Ontario government finally got around to protecting them in 1897, there were barely any passenger pigeons left to protect.

The last two to be killed in Toronto were caught in the fall of 1890. Ten years later, someone said they saw five of them fly over the Islands. That was the very last time a passenger pigeon was ever seen in Toronto. In 1914, the last member of the species — a twenty-five-year-old named Martha — toppled off her perch at the Cincinnati Zoological Garden. Passenger pigeons were officially extinct.

By then, rock doves had taken over Toronto.

In the early 1900s, domesticated pigeons were still being used in much the same way they’d always been used. Every year at the Canadian National Exhibition, pigeon owners raced thousands of birds. At the Royal Winter Fair, they awarded prizes to the best-bred — they still do. Some were used as game for hunting. Others were used to fight in the world wars: the Canadian Army enlisted pigeons to deliver messages just like the ancient Romans did thousands of years ago. It was a pigeon called Beach Comber who brought back the first word of the disastrous landing at Dieppe. They gave the bird a medal for it.

The feral descendants of those domestic pigeons took to the skyscrapers and bridges of Toronto just like they’d done in cities all over the world. You can see them flying above the city’s muddy downtown streets in archival photographs from more than a century ago. Most of them are many generations removed from their captive ancestors; they’ve reverted to the blue-grey colouring of wild rock doves. But some are still white or pink or brown or speckled or spotted, the genetic heritage of their domestic great-grandparents.

Still, not all of Toronto’s wild pigeons are rock doves from the far side of the ocean. There’s one native species that still calls the city home — the closest living relative of the passenger pigeons. These birds used to be called turtle doves, or rain doves, or Carolina pigeons. Today, we call them mourning doves because their gentle hoots sound like a person crying.

They were here when the first Europeans arrived, too, but in much smaller numbers than passenger pigeons. Instead of dense woods, they preferred open spaces. As the forests of the passenger pigeons disappeared and were replaced by farmers’ fields, mourning doves prospered. Today, there are something like four hundred million of them: they live all over the warmer half of the continent.

Some scientists hope those mourning doves will soon be rejoined by their extinct cousins. The Great Passenger Pigeon Comeback project is using cutting-edge genomics in an attempt to bring the species back from the dead. To find the passenger pigeon DNA they needed, they turned to Toronto. The Royal Ontario Museum boasts the largest collection of passenger pigeon specimens in the world. If all goes to plan, the DNA from those Toronto birds will be used to bring the species back to life and to reintroduce it into the wild, helping to restore forests to their natural cycles. If the ambitious project succeeds, it may just be a matter of time before passenger pigeons fill the skies above Toronto once again.

This story is chapter for my first book, The Toronto Book of the Dead. You can learn more about it here — and you’ll find it at the usual places, including your local independent bookstore.

Free Beer! And The Boozy History of Toronto…

I’m bringing back one of my most popular online courses — and this time it comes with free beer!

Alcohol has always been a dramatic part of life in Toronto — from the days of colonial treachery to modern debates over drinking in parks. In this four-week online course, we'll meet drunken rebels, beer-bashing mayors, notorious bootleggers, and alcoholic politicians. We'll witness booze-soaked murders, prohibition-era shootouts, and the kidnapping of one Canada's wealthiest brewers — plus, the bitter fight over whether drinking should be allowed at all. To truly understand Toronto, it helps to understand how this city has been shaped by centuries of people getting drunk.

The course is being sponsored by the wonderful people at Great Lakes Brewery, who got in touch asking if they could give the students free beer! Of course I said yes! So, if you’re logging in from Toronto, you’ll get a grand total of eight free beers to go along with the course — two for each class. (And if you’d like to do a little of your own research ahead of time so you know what kind of tasty beer you’re in for, you can check out the Great Lakes Brewpub at 11 Lower Jarvis or find them on offer in bars and restaurants around the city.)

The course begins September 27 and runs for four Wednesday nights. And as always, paid subscribers to the newsletter get 10% off!

Thank you so much to those of you who have already made the switch to a paid subscription! It’s because of you that The Toronto History Weekly exists. The newsletter is a ton of work, but with every new paid subscriber it gets a little bit closer to being self-sustaining. We’re not quite there yet, but it’s not far off! If you haven’t already become one of the absolutely wonderful people who support The Toronto History Weekly with a few dollars a month, but would like to… you can do it by clicking right here:

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

SAD ARCHITECT NEWS — One of Canada’s most celebrated and beloved architects passed away earlier this month. Raymond Moriyama designed the Ontario Science Centre and the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (both of which are currently under threat) as well as the Toronto Reference Library, the Scarborough Civic Centre and the Bata Shoe Museum, plus the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa and Science North in Sudbury — to name just a few. I’m hoping to write more about his life in the newsletter soon, but for now you can read Alex Bozikovic’s piece in the Globe and Mail, which calls him “one of the leading figures in a generation of architects whose work reshaped Canada’s built landscape and especially its public buildings, aiming to construct a unified and inclusive society… Raymond Moriyama gave us that vision and that commitment; we have an obligation to pay it back.” Read more.

SAD BUILDING NEWS — Demolition has begun on 888 Dupont. I wrote about the building’s fascinating history in the newsletter this summer, which includes a stint building parts for the wood-and-cloth Mosquito bomber during the Second War World. Read more.

NEW VILLAGE NAME NEWS — Jack Landau writes that Black Creek Pioneer Village is changing its name for the second time in its history. Originally called Dalziel Pioneer Park, it will now be known as The Village at Black Creek. They’re also considering an expansion of the museum and visitor’s centre in the years to come. No word yet, it seems, on whether the Pioneer Village subway station will eventually end up updating its name too. Read more.

WORRYING CUTE CAFÉ NEWS — One of my favourite little hidden gems in the city is facing an uncertain future. Park Snacks is a wee café that looks out over Riverdale Park West, just outside Riverdale Farm and the Necropolis. It’s part of a house that has stood on that spot since the 1870s and is now up for sale. Here’s hoping the café lives on after the sale! Read more.

VALLEY GANG NEWS — Bob Georgious shares more of the story of the notorious Brooke’s Bush Gang that terrorized the area around the Don Valley back in the middle of the 1800s. Read more.

MASSIVE MOVIE SCREEN NEWS — Work on the restoration of the Canada Malting Silos at the foot of Bathurst Street continues. And as Jack Landau writes, part of the plan is to turn one side of them into a gigantic projection screen. Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

SILENCE TO STRENGTH: A CONVERSATION WITH CHRISTINE MISKONOODINKWE SMITH

September 14 — 6:30pm — Online — Toronto Public Library

“From the 1960's through the 1980's, many Indigenous children were taken from their communities and placed in non-Indigenous homes. The programs and policies that enabled child welfare authorities to do this is referred to as The Sixties Scoop. In this Live & Online program, author, editor, and journalist Christine Miskonoodinkwe Smith discusses her work in shedding light on this period.”

Free!

WRITING CHANGE IN THE ANNEX WALKING TOUR

September 16 — 1pm — Spadina Road Library — Heritage Toronto

“Celebrated author Katherine Govier will explore the culture and vibrancy of the Annex neighbourhood of the 1970s and the 1980s, through the work of women writer’s who called the neighbourhood home. The presentation will explore the history and culture of the surrounding Annex neighbourhood and emphasize the important women writers and advocates who lived and worked in the neighbourhood, and how their work shaped not only Toronto but Canada.”

Free with registration!

MISADVENTURE ON THE HUMBER

September 21 — 7:30pm — Lambton House — Heritage York

Heritage walk and film premiere. “August, 1968. In the lovely west end neighbourhood of Warren Park, four girls and a dog were enjoying one of the last days of summer vacation. While swimming in the river, a sudden storm hit, stranding them on the abutments. This event — with a short film and talk — recounts the events of that day, with the now-adult people who have lived to tell the tale.”

TORONTO’S MAYORS FROM MUDDY YORK TO MEGA CITY

September 21 — 7:30pm — Montgomery’s Inn — The Etobicoke Historical Society

“Frank Nicholson will help us see the history of Toronto unfold through the careers of some of the sixty-five chief magistrates the city has had since being incorporated in 1834, including our first mayor, William Lyon Mackenzie, the leader of the Rebellion of 1837, and Mel Lastman, who oversaw the amalgamation of the city and its suburbs creating Megacity, our current city, twenty-five years ago.”

Exclusively for members of the Etobicoke Historical Society; an annual membership is $25.

ANNUAL GOVERNOR SIMCOE WALKING TOUR

September 23 — Part 1: 9:30am & Part 2: 1pm — Swansea Historical Society

“As in past years, this FREE guided walking tour will retrace a portion of Simcoe’s 1793 expedition up the Toronto Carrying Place portage route. As in past years, Part 1 of the tour will start at 9:30 am at the Rousseau plaque (8 South Kingsway, beside the Petro Canada station), heading north, mainly along Riverside Drive, and finishing near Bloor Street. After a break for lunch on Bloor Street, Part 2 will start at 1:00 pm at the Alex Ling Fountain (north-west corner of Bloor and Jane Streets), and then head farther north, mainly following residential streets a short distance east of the Humber River. Participants are free to join or leave the walk at any point along the route.”

Free!

ST. JOHN’S NORWAY CEMETERY WALK

September 23 — 1pm — Meet at the north-west corner of Woodbine & Kingston Road — The Beach & East Toronto Historical Society

A walking tour with Gene Domagala. “Celebrating the 170th anniversary of the cemetery and St. John’s Norway Anglican Church.”

Free!

THE 130 YEAR HISTORY OF AN EAST TORONTO HOUSE

September 27 — 7pm — The Beaches Sandbox — The Beach & East Toronto Historical Society

“The Beach & East Toronto Historical Society in partnership with The Beaches Sandbox presents Canadian golf historian Ian Murray with Paul Nicosia. The 130 years history of an East Toronto house and its remarkable family of stonecutters and golfers.”

Free!

Free!

MR. DRESSUP TO DEGRASSI: 42 YEARS OF LEGENDARY TORONTO KIDS TV

Until September 23 — Wed to Sat, 12pm to 6pm — 401 Richmond — Myseum

“The TV shows of your childhood hit closer to home than you might think. From 1952 to 1994, Toronto was a global player in a golden era of children’s television programming. For over four decades, our city brought together innovative thought leaders, passionate creators and unexpected collaborations – forming a corner of the television industry unlike any other in the world. Toronto etched itself into our collective consciousness with shows like Mr. Dressup, Today’s Special, The Friendly Giant, Polka Dot Door, Degrassi, and more. Journey through Toronto’s heyday of children’s TV shows in this playful exhibition.”

Free!

TORONTO AS COMMUNITY: FIFTY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHS

October 5 — West Toronto Junction Historical Society

“Vincenzo Pietropaolo’s presentation on his new book ‘Toronto as Community: Fifty Years of Photographs.’ Those who attended Vince’s presentation of photographs in October 2022 on ‘The Stockyards Then and Now’ will be thrilled to have another session with him and his wonderful photos and commentaries.”

SPACIOUSNESS

Various dates until Oct 7 — 7pm — Fort York

“Spaciousness is a compelling new theatrical experience that offers a tour like no other. Be transported to the past to encounter a multitude of characters who bring to life expansive stories of love, life, and loss during the War of 1812. Then be brought back to present day with a story of surviving conflict that encourages us towards peace. Traverse the grounds of Fort York and meet a cast of characters while travelling from one historic building to another, becoming immersed in stories of life during wartime.”

$30

THE DON: INMATES, GUARDS, GOVERNORS & THE GALLOWS

October 19 — 7:30pm — Montgomery’s Inn — Etobicoke Historical Society

“Join writer and researcher Lorna Poplak as she presents the facts behind the Don Jail’s location and construction, and shares tales about inmates, guards, governors, gangs, officials, and even a pair of ill-fated lovers whose doomed romance unfolded in the shadow of the gallows. The illustrated talk will highlight the Don’s tumultuous descent from palace to hellhole, its shuttering and lapse into decay, and its astonishing modern-day metamorphosis.”

Members only; an annual membership is $25.

A NIGHT AT THE MUSEUM

October 20 — 7pm — Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Join Toronto’s First Post Office & special guest, Richard Fiennes-Clinton, as we experience the museum after hours with a presentation on the traditions surrounding the Victorian culture of death and dying & the spread of spiritualism in Toronto with a look at the rising popularity of capturing ghosts on film! You’ll also craft your own Victorian mourning wreath to take home and display in plenty of time for Hallowe’en. All materials are included in the ticket price.”

$11.98 for members; $17.31 for non-members.