Our story begins in 1917, back when Toronto was still filled with horses. The city had relied on them ever since it was founded. For more than a century, they drew carriages and sleighs, hauled freight, even pulled our early streetcars and fire engines. There were thousands of them working in the city. Now there were thousands of cars and trucks, too, but the era of the horse wasn't quite over yet.

And that meant the streets of Toronto were still filled with their poop.

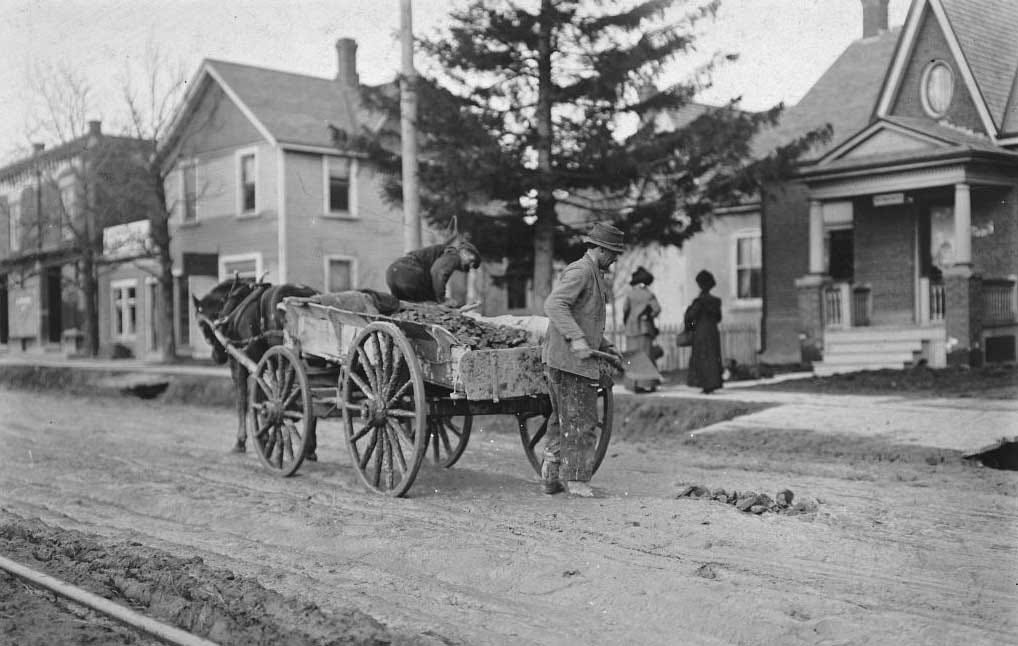

Cleaning up all that manure and other rubbish was a very big job. The Street Cleaning Department had more than five hundred employees, many of them "scavengers" who tracked down waste, piling it into their wagons to be driven off to the dump. They seem to have been pretty good at it. Toronto earned a reputation for being one of the cleanest cities on the continent (right up there with the other shining beacon of urban hygiene at the time: New York City). The scavengers took a lot of pride in their work. They held an annual parade to show off their manure wagons, and many even kept them decorated throughout the rest of the year.

But one of those decorations was about to bring the entire department to a standstill, leaving the people of Toronto burying and burning their own garbage as a fierce battle was waged between two powerful factions with two very different visions for our city's future.

On one side was the scavengers' boss: The Street Commissioner. George Wilson was a new kind of civil servant; he was one of the reformers determined to change the way Toronto worked. They were sick of the old guard who ran the city based on cronyism and political favouritism. They wanted to take a more scientific approach, introducing new systems and metrics in a quest to make the government more efficient, and to make personnel decisions based on merit instead of social connections.

On the other side, there was the old guard: The Orange Order. The organization had been founded in Northern Ireland, fiercely Protestant and passionately anti-Catholic, devoted to the British Empire and its monarchy. The Orange Order had found fertile ground in Toronto, a city that was both very Irish and very Protestant. Orangemen had ruled here for decades. For more than a century, nearly every single mayor in our city was Orange, and the vast majority of public employees too. Including sanitation workers.

But now reformers like Wilson were finding new ways to chip away at that Orange power. In the Street Cleaning Department, a new Code of Discipline was introduced along with standardized penalties for those who didn't follow it — no loitering, no smoking, no gossiping, no taking home prize pieces of garbage for yourself — all in the name of improving service for the public and weeding out the kind of favouritism the Orange Order offered its members. But there was resistance. Wilson and the reformers were making plenty of enemies.

And then came the incident at the stables.

One September day in 1917, Wilson paid a visit to his department's stables on King Street. That's where he noticed something he didn't like. Some scavengers were taking a break, sitting on the sideboards of one of their new motorized trucks. The manure wagon was decorated with a paper windmill and flying a Union Jack. The sight seems to have made Wilson furious.

The Commissioner reprimanded the driver, told him to get rid of the "rubbish" windmill, and tore the flag off the vehicle. He wanted his workers working, didn't want any decorations that might draw attention to their filthy tasks, and felt it was disrespectful to the Union Jack to fly it on a manure wagon.

That confrontation set off a firestorm. Within a few days, it was front page news. Within a couple of weeks, the entire Street Cleaning Department had walked off the job. Toronto was plunged into a very smelly crisis.

Wilson had picked the wrong truck at the wrong time.

In 1917, the First World War was in full swing. Tens of thousands of Torontonians would enlist, many of them eager to fight in the name of the British Empire… and the British flag. Thousands of them would die for it, leaving countless loved ones grieving the loss.

The driver of that manure truck was one of those grieving loved ones. His son had just been killed in the war. So, the Union Jack flying on his manure wagon was an incredibly potent symbol: a show of support for the Empire in a rabidly patriotic age, and a tribute to his fallen child.

For the scavengers, it was the last straw. They already hated their boss and his reforms, seeing his new rules as an attack on their freedom. Their wages had been eroded by wartime inflation. Their workload had been growing along with the city's population. And now, Wilson seemed to be insulting them, assaulting their dignity, suggesting they and their work were too gross to be proud of, too disgusting to be allowed anywhere near the flag.

Eleven days after the incident at the stables, all 509 scavengers and street cleaners quit en masse. They would return, they said, only once Commissioner Wilson had been fired. Until then, the people of Toronto would be encouraged to bury or burn their own garbage. Horse droppings would be allowed to pile up in the streets. The Great Toronto Manure Strike had begun.

The Orange Order backed the scavengers from the beginning. In ripping down that flag, Wilson had given them an opening to attack not only his own position but the entire idea of municipal reform. It was the Orange Order's calls for his dismissal that had driven the story onto the front pages in the first place. They accused him of throwing the flag onto the ground at the stables and calling it "rubbish." Others accused him of being "pro-German;" one Orange leader denounced him as no better than the Kaiser, suggesting Wilson be "sent over to rule Germany." The Order took out a full-page ad in the newspapers to defend the scavengers, promising they would not "stand idly by whilst needless tyranny is operating to crush all spirit and liberty out of the lives of men who have nobly given their dearest and best for their country's needs." Even the mayor — an Orangeman himself — seemed to lean toward the workers' side, telling The Toronto Daily Star he had no problem with them flying the flag on their wagons.

Some even went so far as to suggest the Orange Order had orchestrated the entire strike; if they could get Wilson fired, they would land a blow against reform and win an important victory in the struggle to retain their influence.

Many, however, opposed the strike. The press suggested the scavengers were lazy, just looking to get some time off and have things their own way. Even the wider labour movement failed to back them. Unions had been legalized a few decades earlier, but the street cleaners hadn't joined one or created their own. They even avoided using the word "strike," preferring to call it a "holiday" that would end as soon as Wilson was gone. They had no official ties to organized labour. The Industrial Banner newspaper suggested the scavengers were "misguided;" that they were being manipulated by the opponents of the labour movement.

The strike came to an end just two weeks after it started. The workers agreed to a let an arbitration board settle the matter. And after a few months of deliberation, the board sided with Wilson. They denounced the street cleaners' actions, declared that the decorations were inappropriate since manure wagons should be "as inconspicuous as possible by reason of the nature of the work in which they are engaged," and agreed that "the Union Jack is not honoured by its association with conveyance used for haulage of objectionable matter.”

The scavengers had lost.

But they weren't about to give up that easily. Within months, they'd formed their own official union. The Civic Employees' Union represented not just sanitation workers, but employees from a range of city departments. It quickly counted well over a thousand members. The workers' power was growing.

Just months after their failed strike, the scavengers and street cleaners walked off the job again.

This time, they were joined by hundreds of other city employees. Now it wasn't about the flag or Orange power; it was about fair wages and working conditions. They demanded higher pay in response to inflation and the rising cost of living. They wanted an eight-hour workday. And clear guidelines around sick pay and vacation time. With the war coming to an end, the Canadian labour movement was on the rise, soon to reach a climax with the Winnipeg General Strike. Support for Toronto's striking municipal employees poured in from streetcar workers, plumbers, machinists, telegraphers and more. A Toronto General Strike was being threatened by tens of thousands of people across the city who were willing to risk their own wages in order to support their fellow workers.

In the face of that united opposition, city council gave in. A commission was created to settle the issue and gave the workers most of what they were asking for.

The second strike was over. And this time, the scavengers had won.

I first learned about the strike from Charles Hurl’s great article about it, “From Scavengers to Sanitation Workers: Practices of Purification and the Making of Civic Employees in Toronto, 1890–1920,” which you can check out yourself here.

A VERY GROSS HISTORY OF TORONTO

Announcing a new online history course! Taught by me! Over the course of four weekly lectures! Filled with icky stories! Here’s the full course description:

Ewww. Sure, Toronto has a reputation for being a remarkably clean city. But it also has a long history of being a filthy, disgusting mess. From its days as a muddy frontier town with mysteriously green puddles collecting in its streets to hordes of rats swarming the slopes of the Don Valley, we'll spend four lectures digging into some of the ickiest, smelliest, slimiest stories Toronto history has to offer. And we'll learn a lot about our city and how it works in the process.

THE WEREWOLF OF QUEBEC

We released a spooky new episode of our Canadiana documentary series today! In the late 1700s, newspapers in Quebec reported that a werewolf was on the loose in the colony, one of many said to have terrorized French-Canadian settlers in centuries gone by. We tell the tale in a short video that is, like all our episodes, free to watch on YouTube (with some bonus unicorn history thrown in at the end):

THE FABULOUS JACKIE SHANE

Jackie Shane got her own Heritage Minute last week. Not only was she was one of the greatest soul singers Toronto has ever known, she was one of its most remarkable historical figures. Her live album, recorded at the Saphire Tavern on Jarvis in the summer of 1967, is one of the best I’ve ever heard — remarkable not only because the music is incredible, but because it’s a recording of a Black trans woman defiantly talking about her identity on stage more than half a century ago.

Shane got a whole chapter in my romantic history of the city, The Toronto Book of Love. Here’s a little of what I wrote about her:

She was a singer who made every song her own, a performer electric with coiled energy, and an entertainer who knew damn well how to put on a show. In the quiet-er moments of her sets, her confessional banter allowed her to connect with an audience in an intimate way. Whoever they were — whoever they loved — she could make them feel like they weren’t alone.

When she first started playing at the Saphire Tavern, she made sure her queer fans would feel welcome, talking to the owner to guarantee it. “In fact, I told Mrs. Stone,” she remembered, “‘Look, gay people must be able to come and see me. As long as they come just like everyone else and obey the rules and such, I don’t want anyone kept from seeing me. I want them to come.’ We had an understanding.”

Shane drew audiences both queer and straight, Black and white — as well as everyone in between. And when they ventured inside the Saphire, they found her there onstage, blurring gender lines and talking openly about her sexuality. On the live album, her banter with the audience is filled with references to loving both men and women. “I’m going to enjoy the chicken,” she told the crowd, using a slang term for young men, “the women, the chicken, and everything else that I want to enjoy. That’s how I live. That’s why I’m so happy all the time.” And she took that message well beyond the confines of the Saphire. She played in high schools and YMCAs across the city, and toured communities all over southern Ontario. A curling rink in Scarborough. The town hall in Newmarket. A dance club on the shores of Lake Simcoe. As well as her adult fans, she reached countless queer teens who didn’t have many public role models.

It wasn’t always easy. People gawked and snickered, even in Toronto. “You know,” she explained, “when I’m walking down Yonge Street, you won’t believe this, but you know some of them funny people have the nerve to point the finger at me and grin and smile and whisper.” She often presented as a gay man in drag. Local news- papers wrote columns speculating about her gender; at least one sent a journalist to ask her about it to her face.

Not that she would let that stop her. “So, now listen, baby,” she told the crowd at the Saphire, “when you see Jackie walking down the street, or I walk into a restroom that you’re in, I want you to laugh and talk and grin and point the finger at me because if I ever walked out and they didn’t point and whisper about me, I’d go back in and look in the mirror and stick out my tongue because I thought I was sick or something, I done lost my touch.... Every Monday morning, I laugh and grin on my way to the bank.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE TORONTO BOOK OF LOVE

Before we continue, just a very quick reminder that The Toronto History Weekly will only survive if enough of you are willing to switch to a paid subscription. Only about 5% of readers have made the switch so far, which basically means that by offering a few dollars a month you’ll be giving the gift of Toronto history to 20 other people. You can make the switch by clicking here:

QUICK LINKS

The best of everything else that’s new in Toronto’s past…

HALLOWEEN RIOT NEWS — Daniel Panneton takes a look at All Hallows’ Eve in 1945, when Toronto teenagers rioted in Beaches and other neighbourhoods across Toronto during what The Globe called “the rowdiest Hallowe’en in the city’s history.” Read more.

DRAG QUEEN NEWS — Hogtown 101 shares some photos from Toronto’s famous Halloween Ball, snapped outside the Letros Tavern on King Street in 1967. It was the one night of the year where drag queens didn’t have to worry about police arresting them for wearing women’s clothing, though the events also drew angrily homophobic crowds…

You can also learn more about the Halloween Ball from the Arquives. Read more.

RAINBOW CLOCK TOWER NEWS — …the Halloween drag ball eventually migrated up Yonge Street to the St. Charles Tavern, held beneath its iconic old fire hall clock tower. That tower has moved as part of a new development and was just unveiled. Now, it features some rainbow colouring in a nod to its LGBTQ+ past:

FROZEN CHARLOTTE NEWS — On the Archaeological Services Inc. blog, Janice Mitchell shares the tale of a creepy, mass-produced Victorian doll and how it became associated with a grisly myth. Read more.

HOMOPHOBIC ELECTION NEWS — Jamie Bradburn tells the story the 1980 mayoral race, which saw John Sewell running for re-election after making waves at City Hall with his criticisms of the police and support for LGBTQ+ communities. Read more.

RESISTANCE NEWS — Amira Elghawaby writes that commemorating events like October’s Islamic Heritage Month, Latin American Heritage Month, and Women’s History Month “are in fact acts of resistance and defiance.” Read more.

TORONTO HISTORY EVENTS

TORONTO’S BEACH NEIGHBOURHOOD IN FICTION AND NON-FICTION

November 8 — 6:45pm — Toronto Public Library’s Beaches branch

“Jane Cawthorne's novel, Patterson House, is set in the Beach around 1930 and is about the life of the Patterson family. Katherine Taylor's non-fiction work, Toronto: City of Commerce 1800-1960, looks at Toronto's commercial and industrial history. Both authors will share passages of their work and will discuss the considerations they had as they captured a historical setting.”

Free with registration!

AN UNRECOGNIZED CONTRIBUTION: WOMEN AND THEIR WORK IN EARLY 19th CENTURY TORONTO

November 10 — 7pm — Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Elizabeth Gillian Muir will speak about her newly released book, An Unrecognized Contribution: Women and their Work in early 19th century Toronto, highlighting scores of women and the work they undertook during a period of great change for the city. ‘Women in nineteenth-century Toronto were integral to the life of the growing city. They contributed to the city’s commerce and were owners of stores, factories, brickworks, market gardens, hotels, and taverns; as musicians, painters, and writers, they were a large part of the city’s cultural life; and as nurses, doctors, religious workers, and activists they strengthened the city’s safety net for those who were most in need.Their stories are told in this wide-ranging collection of biographies, the result of Muir’s search of early street directories, the first city histories, personal diaries, and other documents.’”

$22.23 for non-members; $16.93 for members.

TWO WAYS TO WRITE HISTORICAL TORONTO

November 14 — 7pm — Another Story Bookshop

“Jane Cawthorne’s debut novel, Patterson House, is set in the Beach between 1850 and 1954. Historian Katherine Taylor’s photographic history, Toronto: City of Commerce 1800-1960, nominated for the Heritage Toronto Book Award, traces the ever changing commercial landscape of Toronto and recounts the stories of vanished businesses and their owners and workers. What goes into writing the history of a place? Both Jane and Katherine will read from their work and, in conversation with MC Judy Rebick, will discuss these two very ‘Toronto’ books.”

Free!

RITA LETENDRE: CELEBRATION OF LIFE

November 23 — 7pm — AGO

“Born in Drummondville, Quebec to Abenaki and Québécois parents, Rita Letendre began painting in 1950s Montreal, when she associated with Quebec's prominent abstract artist groups Les Automatistes and Les Plasticiens. After living in Europe and the U.S., she moved to Toronto in 1969. Seeking to express the full energy of life and harness in her powerful gestures an intense spiritual force, Letendre worked with various materials including oils, pastels and acrylics, using her hands, a palette knife, brushes and uniquely the airbrush. Renowned for her bold and visceral style, she pushed the boundaries of colour, light and space to new heights. Her work embodies her ongoing quest for connection and understanding. The free event will include a screening of interviews with Letendre, alongside remembrances by her colleagues, friends and family.”

Free with registration.

AUTHOR TALK: THE BEATLE BANDIT WITH NATE HENDLEY

November 24 — 7pm — Toronto Public Library’s Brentwood branch

“Winner of the Crime Writers of Canada Award of Excellence for Non-Fiction 2022, true crime writer Nate Hendley tells the story of Canadian bank robber Matthew Kerry Smith, aka the Beatle Bandit. The sensational true story of how a bank robber killed a man in a wild shootout, sparking a national debate around gun control and the death penalty.”

Free!

MOST HOPES: HOMES & STORIES OF TORONTO’S LOST WORKERS

November 29 — 6:30pm — Online — Riverdale Historical Society

“RHS welcomes Leslie Valpy, a heritage conservationist practitioner and Don Loucks, a Heritage Architect, to speak about their recent book, ‘Modest Hopes, Homes and Stories of Toronto’s workers from the 1820s to the 1920s’, which celebrates Toronto’s built heritage of row houses, semis, and cottages and the people who lived in them. Toronto’s workers’ cottages are often characterized as being small, cramped, poorly built, and in need of modernization or even demolition. But for the workers and their families who originally lived in them from the 1820s to the 1920s, these houses were far from modest. Many had been driven off their ancestral farms or had left the crowded conditions of tenements in their home cities abroad. Once in Toronto, many lived in unsanitary conditions in makeshift shanty-towns or cramped shared houses in downtown neighbourhoods such as The Ward. To then move to a self-contained cottage or rowhouse was the result of an unimaginably strong hope for the future and a commitment to family life.”

Free, I believe!

AN ILLUSTRATED TALK ON THE HISTORY OF ADELAIDE STREET

November 30 — 7:30pm — Online — North Toronto Historical Society

“Once home to upscale residences and important public services, Adelaide Street's buildings later housed light industries such as publishing. There are still examples of the detached and row housing that dominated west of Yonge in the late 1800s. The financial district extends to Adelaide and the condo scene here is ever-changing. Architectural historian and NTHS member Marta O'Brien will present an illustrated talk on the history of Adelaide Street.”

Free with registration, I believe.

DEATH OR CANADA

December 1 — 7pm — Toronto’s First Post Office — Town of York Historical Society

“Dr. Mark G. McGowan will speak about his most recently published book, Death or Canada: The Irish Famine Migration to Canada, 1847, and his exploration of this migration's impact on Toronto. ‘Historian Mark McGowan delves beneath the surface of statistics and brings to light the stories of men and women who had to face a desperate choice: almost certain death from starvation in Ireland, or a perilous sea voyage to a faraway place called Canada.’”

$22.23 for non-members; $16.93 for members.